To say Joe Matt’s world is the street where he lives isn’t much of an exaggeration. In the decade and a half he has been writing and drawing his life in the pages of his comic, Peepshow, Matt has concerned himself with little more than his few personal obsessions: book collecting, girls, music, and the dubbing of pornography—which, inevitably, leads to his related obsession, masturbation. To view the world through the eyes of Matt’s autobiographical “quarterly” is to think such things as Reaganomics, the fall of the Berlin Wall, grunge, the internet, Y2K, and 9/11 never happened. In Peepshow, world events not only take a back seat, they aren’t even in the car.

Matt, thirty-nine, began chronicling the minutiae of his day-to-day existence in 1987, in a series of one-page strips published originally in two comic anthology series, and later collected into a book under the title Peepshow: The Cartoon Diary of Joe Matt. Since 1992, he has published thirteen issues of his comic book, also titled Peepshow, as well as two more books of collected work, the most recent of which, Fair Weather, was released this fall. In its early days, Matt’s strip was most easily—and often—compared to the work of Robert Crumb, the godfather of underground, autobiographical comics, both for its cartooning style and its themes of self- and sexual obsession. Since then, Matt has developed storytelling and artistic styles of his own, as well as a small cast of supporting characters—Matt’s real-life friends and cartoonists Seth and Chester Brown—who are forever subjected to his notorious cheapness, his whining, and his relationships with women, both real and imagined.

While Peepshow may not enjoy the sales numbers of Superman or Spider-Man (though, since Peepshow’s first issue, the circulation of superhero comics has plummeted, narrowing the gap significantly), Matt’s following is as hard-core as it is impressive. Though a glance at the letters page of any given issue suggests many of Matt’s fans fall into the stereotypical fanboy category (young men living in their mothers’ basements, substituting pen-and-ink fantasy women for the real thing), Peepshow’s subscriber list also crosses over into the nerd avant-garde. Self-professed fans include Crumb himself (“I can’t wait to see what happens next”), Simpsons creator Matt Groening (“I’m a Joe Matt fanatic!”), musician Moby (“Peepshow rocks hard, poppa”), and comedians Jeanne Garofalo and Ben Stiller. Even Rivers Cuomo, of the nerd-rock group Weezer, once gushed, “Your work has been a big influence on my songwriting.” But perhaps even more bewildering is Matt’s popularity with young women (two of Matt’s recent relationships, including his current girlfriend, were all initiated either via Peepshow’s letters page or through comic conventions). “A part of it is his portrayal of himself is not entirely unsympathetic,” says Peter Birkemoe, owner of the Beguiling comic shop in Toronto’s Mirvish Village. “I think he confirms all the fears girls have about men, maybe not their worst fears, but they see a guy who’s confessing all these horrible things, and for some reason they seem to find that endearing.”

Peepshow’s circulation of about eight thousand is very high for an independent comic. (Any given Batman or Superman title may sell a hundred thousand copies per issue.) Only a few independents, such as Adrian Tomine’s Optic Nerve or Daniel Clowes’s Eightball, fare significantly better, both reaching the twenty-thousand range. Independent comics are not huge money-makers, and, unlike many of his contemporaries, such as Seth and Tomine, Matt doesn’t increase his income with magazine illustration work. (The meager income he earns from his Peepshow royalties is supplemented only by his savings, upon which he maintains “an iron grip.”) While the Joe Matt depicted in Peepshow considers such work a violation of his artistic integrity, the real Joe Matt admits he’s just too lazy to bother. Instead, he keeps his expenses low, and enjoys a comfortable life, even if it may not be as luxurious as that of his many famous admirers.

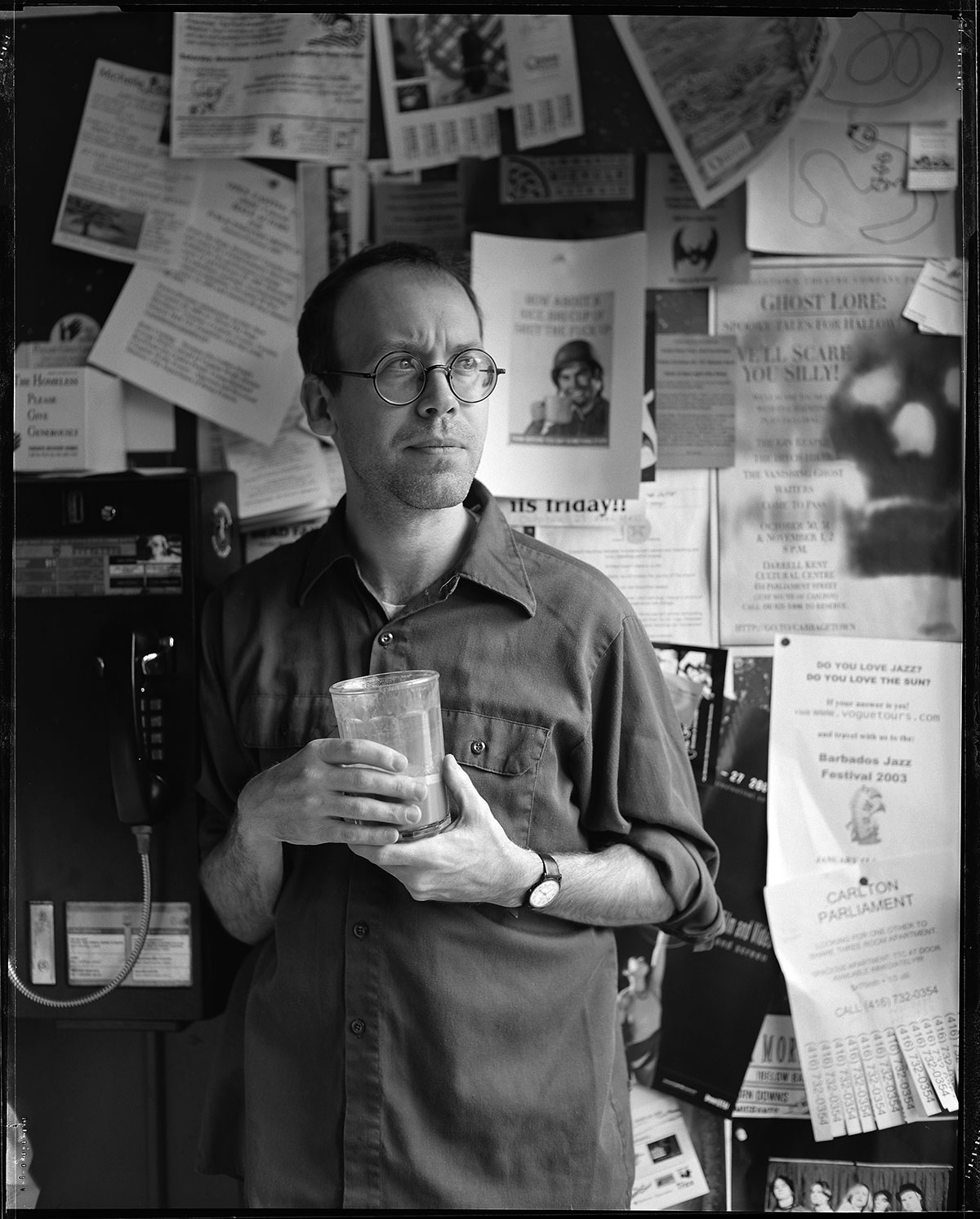

Though he has resided in Canada for fifteen years—the last eleven of which he has spent in a boarding house in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood—Matt grew up in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, thirty miles from Robert Crumb’s childhood home, Philadelphia. His father spent twenty years working for Amtrak, while his mother studied painting at the Philadelphia College of Art, only to give it up shortly after graduation to raise a family.

Many of the eccentricities that make Joe Matt the comic book character so interesting to read—his collecting of daily newspaper strips, his selfishness, his obsession with collecting literally any comic-related memorabilia—began during the real Joe Matt’s youth. This early love of comics—and the encouragement of his artist mother—inspired Matt’s early doodles.

In high school, Matt found that his increasing ability to illustrate quickly won him friends in the popular group, something the nebbish youth had previously been unable to obtain. “It made me feel good,” says Matt. “The response I got from kids and my parents and stuff was much more gratifying somehow than getting good grades.”

It wasn’t until his second year of art school (like his mother, he attended the Philadelphia College of Art) that Matt was introduced to the work of Crumb. Crumb’s autobiographical work was painfully honest. Though more overtly political than Matt, Crumb was a sexual neurotic, and his art ran the gambit from cartoonish to grotesquely realistic. This discovery began to quickly have an influence on Matt’s choice of reading material—drawing him away from the superhero camp—and, eventually, on his own work. “It already felt nostalgic, like something from the past, even though it wasn’t,” says Matt of his early affinity for Crumb. “His style was obviously influenced by [political cartoonist] Thomas Nast; the really early cartooning of the twenties and thirties.”

To Matt, college was the ticket to a career as an illustrator. Today, he admits that, at the time, he had no idea what being a career illustrator meant or how to go about becoming one, and recalls with horror days spent shopping his portfolio to magazine after magazine upon graduation. “I didn’t have the social graces to endear myself to these art directors,” he says. “I just stood there while they looked at my portfolio.” Matt began drawing minor, everyday events from his life in a sketchbook. Friends read the strips and convinced him to start an autobiographical comic of his own, in the tradition of Crumb. These early white-on-black pages chronicled Matt’s miserable summer-long stint colouring Batman, his moves from Lansdale to Montreal to Toronto, and his first meetings with Seth and Chester Brown. (A reviewer once referred to Seth and Brown’s Peepshow appearances as “the indie comics equivalent of The Jetsons Meet the Flintstones.) Many strips seemed to act as a form of therapy for Matt, dealing with events from his childhood and teen years, his past relationships with women, and his penchant for pornography. Most, however, focused on his relationship with then-girlfriend Trish. Given their monthly frequency, new strips often found inspiration in Trish’s reactions to previous strips, resulting in a comic book vérité style that was both uncomfortable and entertaining to read. Readers were also given a glimpse at the increasing tension in Matt’s relationship with Trish, caused largely by the couple’s sex life taking a back seat to Matt’s love of pornography and his chronic masturbation.

After a run of nearly four years, Kitchen Sink Press collected Matt’s adventures and released the original Peepshow book. At this time, Matt decided to move to the more narrative-friendly format of the comic book. In 1991, he joined the growing roster of Drawn & Quarterly, an up-and-coming Montreal publisher that had printed many of his Peepshow strips in its eponymous anthology series. (Drawn & Quarterly also became home to the work of Seth and, eventually, Chester Brown.) The first issue of Peepshow depicts a lustful Matt fantasizing about a girl whom Trish had recently befriended. Committed to his frank autobiographical style, Matt lays bare his infatuation and his futile attempts to impress her behind Trish’s back. The real-life result—as seen in the next issue—involves a humiliated Trish finally bringing an end to the couple’s tumultuous four-year relationship. “I didn’t expect it. I wanted her to just believe me that I was exaggerating this for the effect of outraging the readers,” Matt says. “I wanted her to stand by me like Howard Stern’s wife does, and realize that this is just a shtick. But, in hindsight, that was the end, and my infatuation with that girl was indicative of this crappy relationship. It wasn’t healthy. I obviously didn’t want that relationship to continue, but part of me did. Part of me just wanted to be alone to watch as much porn as possible because I hadn’t lived that dream yet, so that’s the biggest reason I think I drove her away. In the comic, I gave her a black eye; twelve years later now, I still don’t hear the end of it. I never drew the hundreds of times she was punching me. I was like a battered husband. I tried to make myself look bad and part of that was admitting I had a crush on this girl.”

The final pages of Peepshow’s second issue depict Matt on the verge of an insane frenzy upon realizing Trish is really gone, before collapsing in a fit of sobs. The issue ends with a touching flashback to the couple’s second date, where a bashful Matt first admits his love for Trish. Over the following four issues, Matt attempts to come to terms with his loss, while consistently failing to find love with anyone new. Peepshow’s first extended story ends with Trish compromising her artistic integrity—in Matt’s eyes, at least—by taking an animation job with Disney and moving to California, leaving Matt alone in his room, seemingly destined to continue loving only his pornography—and himself.

The first six issues of Peepshow were collected into one volume as The Poor Bastard, originally published in 1997 (the book has sold more than seven thousand copies to date). While Matt’s cult status had slowly been building up to that point, The Poor Bastard cemented his reputation as one of the leading comic book artists and storytellers of his generation. “Despite some deviations from fact, The Poor Bastard was a much more honest portrayal than people were used to seeing,” says Birkemoe of The Poor Bastard’s commercial and critical success. “While someone like Crumb lays everything bare, people can’t conceive themselves confessing the way he does. With Joe, they can.”

Unlike the world of big-budget superhero comics, where an artist and a writer will often co-create a book, assisted by a dedicated inker and letterer, underground comics are generally the vision of one person. This person is usually solely responsible for the story, art, lettering, and inking. Considering Matt’s lifelong love of comics (he continues his childhood hobby of collecting newspaper dailies, though in the somewhat more expensive form of amassing Frank King’s run of Gasoline Alley from the nineteen-twenties to fifties), not to mention his profession, it is somewhat odd that he prefers to think of himself as a writer rather than a cartoonist. Given the choice, Matt says he would rather write than draw. “Chris Ware [author and artist of The Acme Novelty Library and Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth] said something like, ‘If you put too much effort into the pictures, they’re going to be distracting from the read, you’re going to slow it down.’ Comics are for reading. Sketchbooks are for looking at. I would like to just write, but I feel like it’s easier to be a bigger fish in the small pond of comics. Because there’s no money in comics, really, there aren’t that many people doing it.”

At the same time, Matt is also tortured by the artistic process. That, combined with his self-described laziness, caused his quarterly comic book to fall behind schedule after its second issue, soon publishing only twice a year, then once. “Joe would be seeing more sales if he were more prolific,” says Chris Oliveros, publisher of Drawn & Quarterly. “You need to come out more frequently to build a following. It’s amazing he does so well considering how often he comes out.” But Matt has somehow managed to hold on to his following, despite the fact that, since 1998, he has been averaging only one issue every two years. “I’m so anal-compulsive, the inking is such a horrible nightmare to me. I can barely make a stroke or two before I have to white it out,” Matt says. “The whole thing’s very unpleasant to me. Even when I’m penciling, I’m uptight about thinking the oil from my fingers is going to get on the board and later the brush stroke will hit that slick of oil. It never stops. I really love comics, I feel it’s what I’m best at whether I like it or not, so I shouldn’t be trying to write novels.”

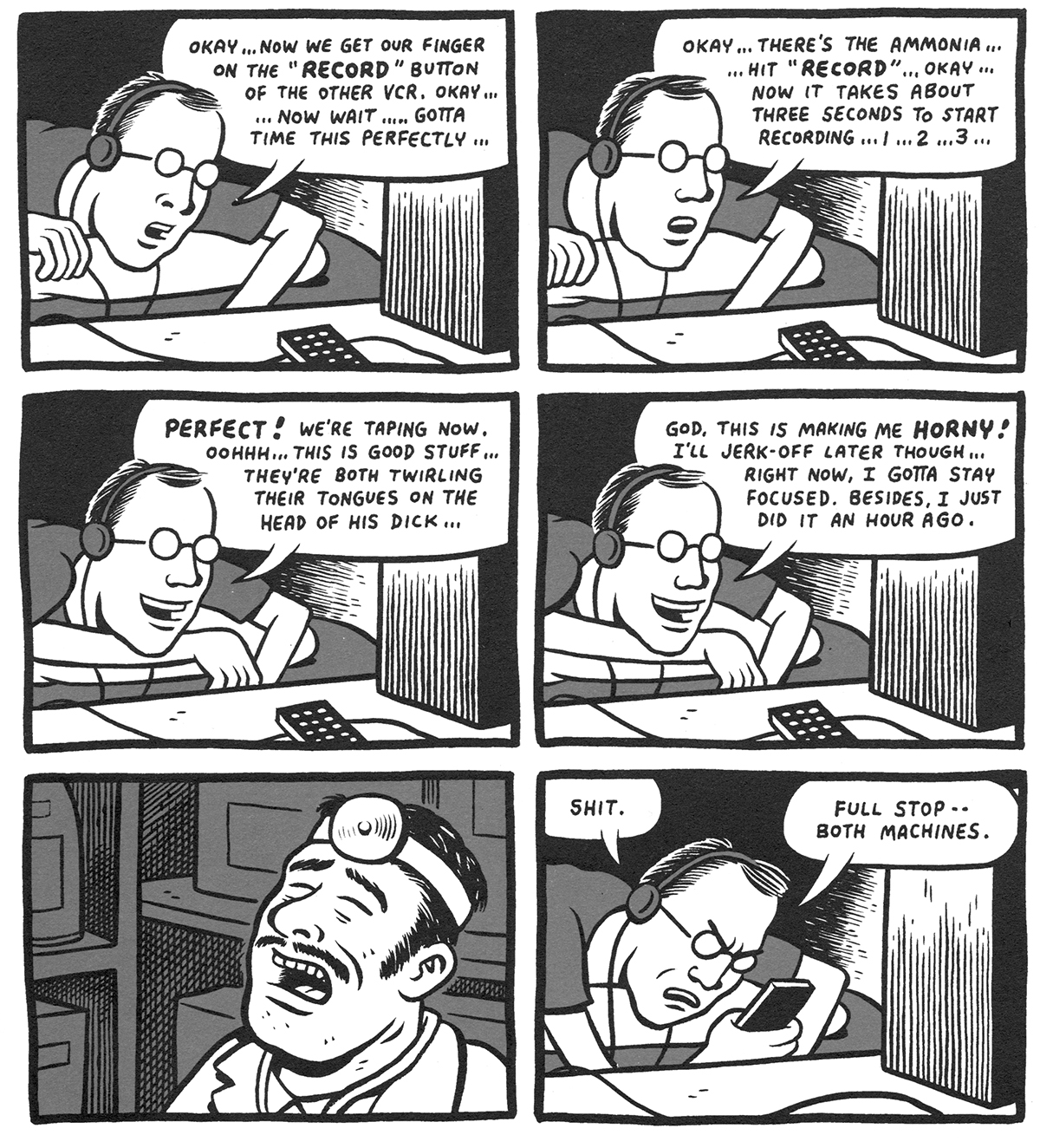

A typical Joe Matt day, as seen in Peepshow No. 12.

Matt’s most recent collected work, Fair Weather, published this fall by Drawn & Quarterly, collects Peepshow Nos. 7–10, originally published from 1995 to 1997. Emotionally drained from his breakup with Trish, Matt broke from The Poor Bastard’s masturbatory self-loathing style, focusing instead on an isolated tale from his childhood. While Fair Weather’s ten-year-old Joe Matt is easily recognizable as the selfish obsessive he would later become in The Poor Bastard, the story’s subject matter could not be further removed from his previous work. “I would have preferred to do something else in retrospect,” Matt says today. “After The Poor Bastard and after losing Trish, I felt like I was so miserable I didn’t want to do anything for years, and I didn’t even know what to write about. I felt like just doing anything would be better than nothing, so I chose that story.” Peepshow’s letters page has always received an equal number of letters both praising Matt for his storytelling and berating him for his lifestyle and his treatment of Trish. With Fair Weather, however, Matt drew his first batch of hate mail directed at Peepshow’s storyline (“What a royal piece of roach shit,” wrote one reader). Many who had loved The Poor Bastard for its portrayal of Joe Matt, porn-addicted, masturbating freeloader, seemed to have little tolerance for the back story, especially considering Peepshow’s ever-decreasing rate of publication. “A lot of Peepshow’s appeal is the character of Adult Joe,” says Birkemoe. “The child character is not as complex or interesting. I suspect he may have ended the story early as a result of the criticism.”

Despite his slow output, Matt is determined to continue chronicling his life—all of it. While the move to comic books has allowed more freedom in terms of extended storytelling, it has lost the immediacy and instant reaction of the original monthly strip. Matt’s current storyline, dealing with his addiction to watching pornographic films—and his obsession with editing out their story-forwarding devices and extended close-ups of men to create a series of ultimate highlight reels—began in Peepshow No. 11, published in 1998, and picks up not long after the final installment of The Poor Bastard, published in 1994. Now three issues in (Peepshow’s most recent issue was published in early 2002), Matt is ten years behind in chronicling his life. If he continues his current rate of publication—and assuming he won’t become even less prolific—his projected ten issue story will not end until 2016, by which time Matt will be fifty-three years old. “It’s frustrating. I’ve got such a backlog of things I need to cover,” Matt says. “I have two big relationships behind me that I need to depict in the comic. I sort of feel compelled to write about every sexual encounter. There’s only been a few, but they’re important to me. And my relationships with Chester and Seth, and my relationship with pornography, these are the themes that continue today. There’s a vague plan [to increase production], but days go by and I still don’t do anything. It’s like the last ten years, all the dubbing of pornography I’ve done has occupied maybe fifty per cent of my waking hours. As long as I’m controlling the masturbation and pornography—the compulsion is really my biggest problem—as long as I’m trying to control that, it can only follow that I’ll be more productive. Trying to find that discipline is my personal hell.”