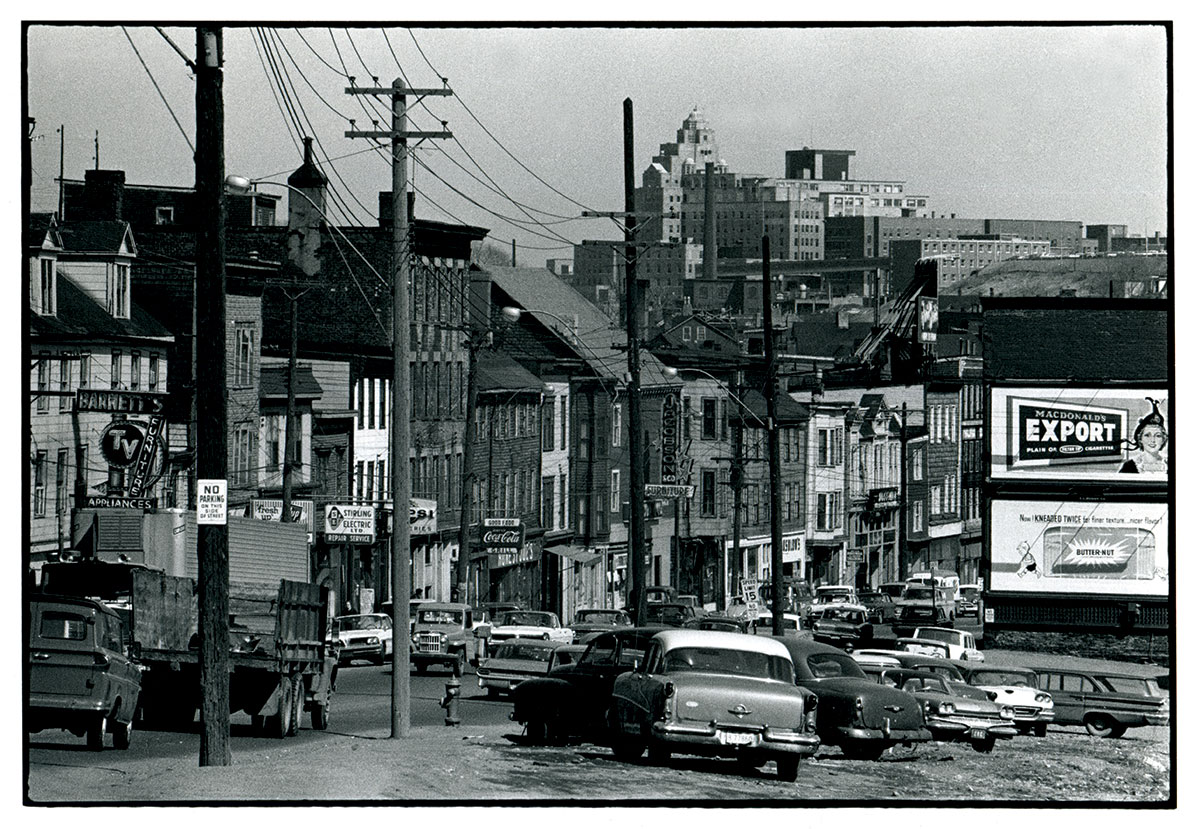

Main Street, 1964, looking toward the art deco General Hospital. Built in 1930, the hospital was shuttered in 1982 and demolished in 1995 when no viable options could be found for its reuse.

Saint John, New Brunswick, feels old. It has always felt old to me. Not old in a cultured, antiquarian way, like Rome, Barcelona, or Paris, but more Dickensian and emphatically classified. At least, in retrospect, that’s how I recall it being for the first ten years of my life, growing up in the city’s east end, and through my teen years, living in the public housing project known as Crescent Valley before finally “moving up” to the sanitized suburb ironically called Forest Hills.

Relatively speaking, this industrial port city on the Bay of Fundy at the mouth of the Saint John River is old—at least in Canadian terms. Saint John is Canada’s first incorporated city, chartered in 1785. It became renowned for producing some of the greatest shipbuilding craftsmen in the world, whose bragging rights would include the construction of the three-masted Marco Polo, which ruled as the fastest clipper ship on the high seas from its launch, in 1851, until it was forced aground on Prince Edward Island and broke up, in 1883.

During the years of the Second World War and beyond, Saint John could boast of having one of the largest dry docks in the world, and along with its port it stood tall alongside such gritty industrial cities as Rotterdam. When you are a port city of that calibre, the world comes to you. It comes from the most exotic places, with names read from the headlines of international papers, and still other places you might only have heard about in geography or history class or in stories read to you before bed.

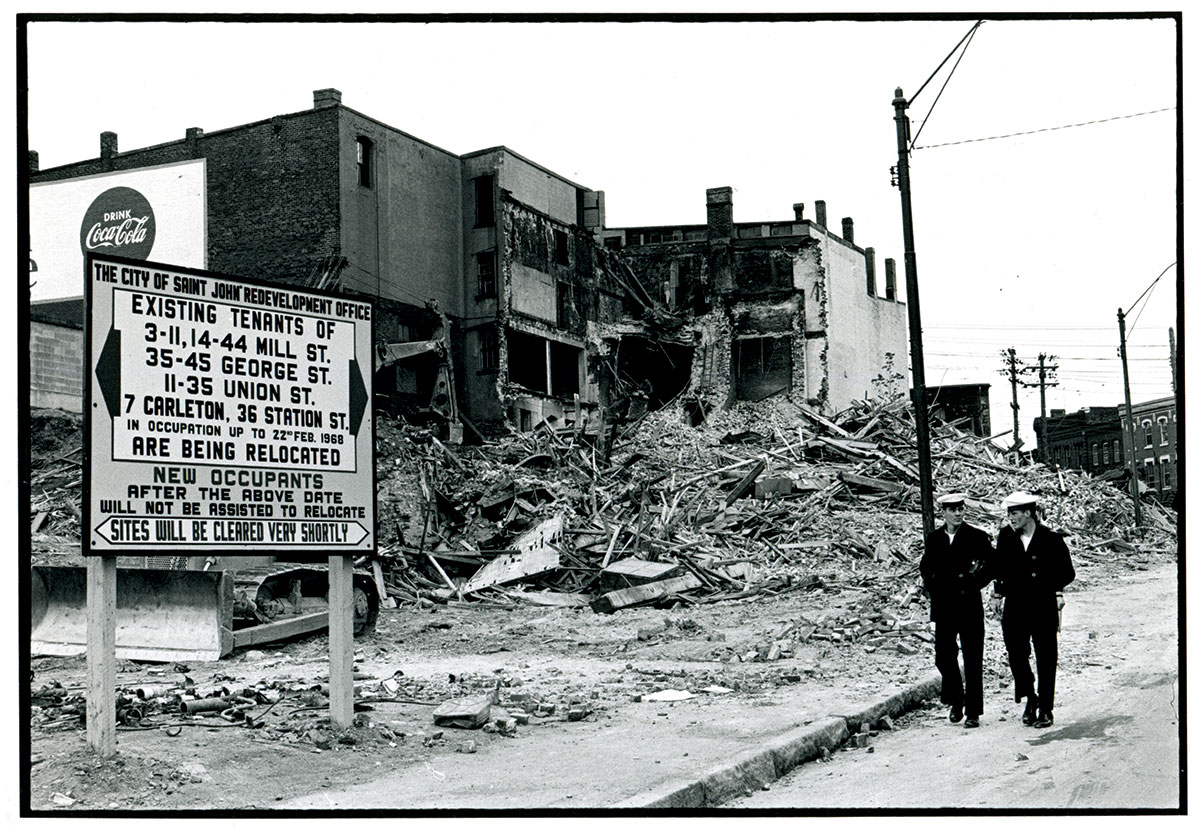

Ever since the city’s Great Fire of 1877, Saint John has been trying to recover. During the urban renewal period of 1960 to 1985, more than four thousand irreparable homes were demolished. However, along with the destruction of physical dwellings, this renewal destroyed neighbourhoods, either replacing them with housing projects or with nothing at all, while gutting the heart of the city and paying more attention to the automobile than to people, an attitude that seems to continue to this day. Jane Jacobs, the renowned champion of new, community-based strategies for city planning, once wrote, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” I often wonder what she would have said if she had been consulted on Saint John’s plans for its future.

The photographs exhibited here are, in my view, nicely voyeuristic. Ian MacEachern, the photographer, is not from Saint John. He was born in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, and only arrived in Saint John from Sydney in the early nineteen-sixties to work as a cameraman at the CBC affiliate CHSJ-TV. His stay in Saint John was brief, but the city intrigued him with its architecture, numerous fires, and imminent urban renewal. He soon was dedicating more and more of his downtime to his photography, documenting the changing face of the city. MacEachern moved to Toronto in 1966 (though returning frequently to Saint John for several years), where he worked as a freelance photojournalist for several magazines, including Maclean’s, Chatelaine, Saturday Night, and Time. MacEachern’s photographs have been exhibited extensively across Canada and the United States, and he now lives with his family in London, Ontario.

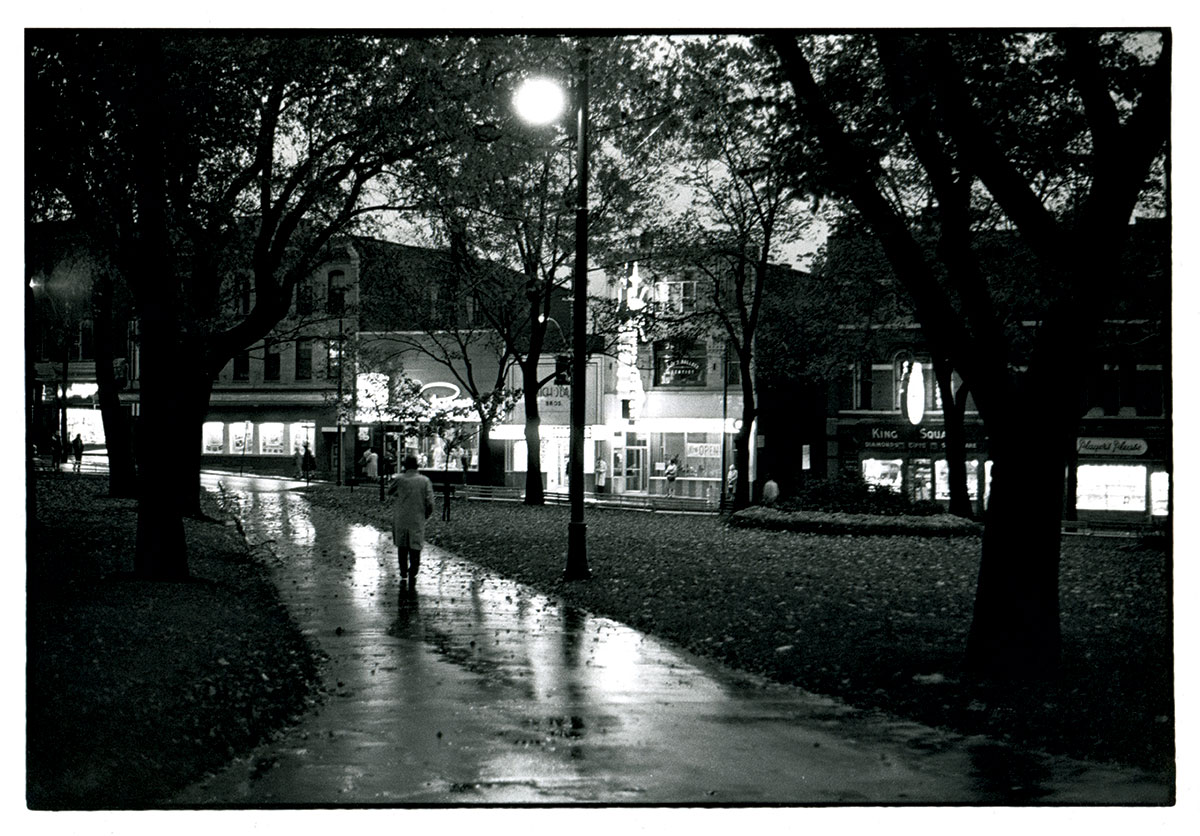

When I look at MacEachern’s photos, I think of a time in the sixties when, as a teen, my friends and I would get into a car and drive “uptown” (our “uptown” was the equivalent of most cities’ downtown or strip). We would circle King’s Square for what seemed like hours, playing the radio and looking for girls. In retrospect, we were playing a role in our own “Canadian Graffiti,” like teens in every small town and suburb across the country. Eventually, we would park and head to a booth at the Riviera restaurant, where we would down a glass of cherry Coke and plan the rest of the night with the other “Riv rats.” Soon we would be back in our car, driving around King’s Square again, dreaming that one day we would get off that wheel and find adventure in a greater world.

Now when I visit Saint John, I can’t help feel that same strain of possibility that I felt when I was young. It still feels like a company town. The antiquated parts of the city appear frozen in time, like one of these photographs, while the newer parts seem still to be struggling for purpose and modernity.

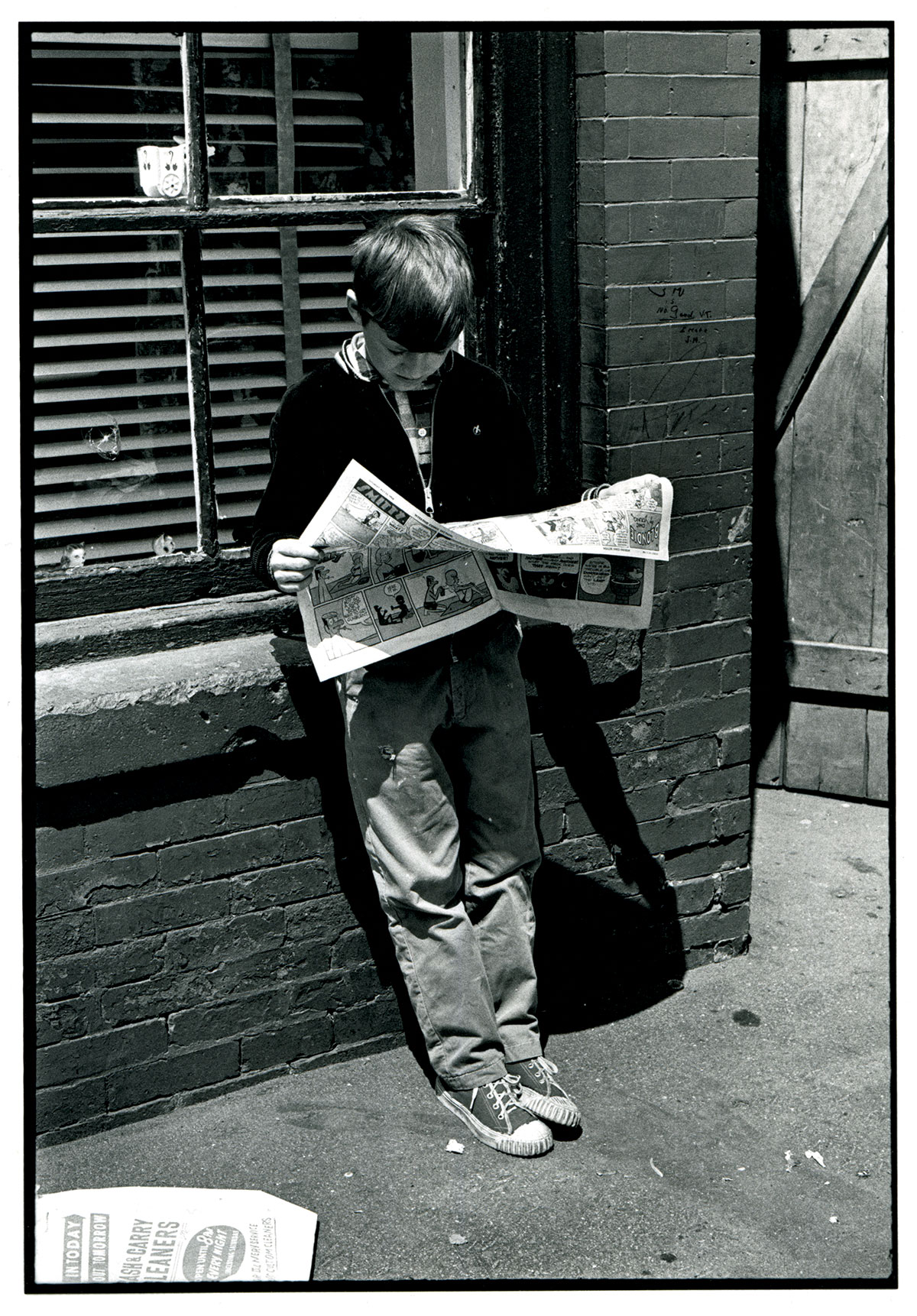

A boy reads the weekend comics, in the south end, 1968.

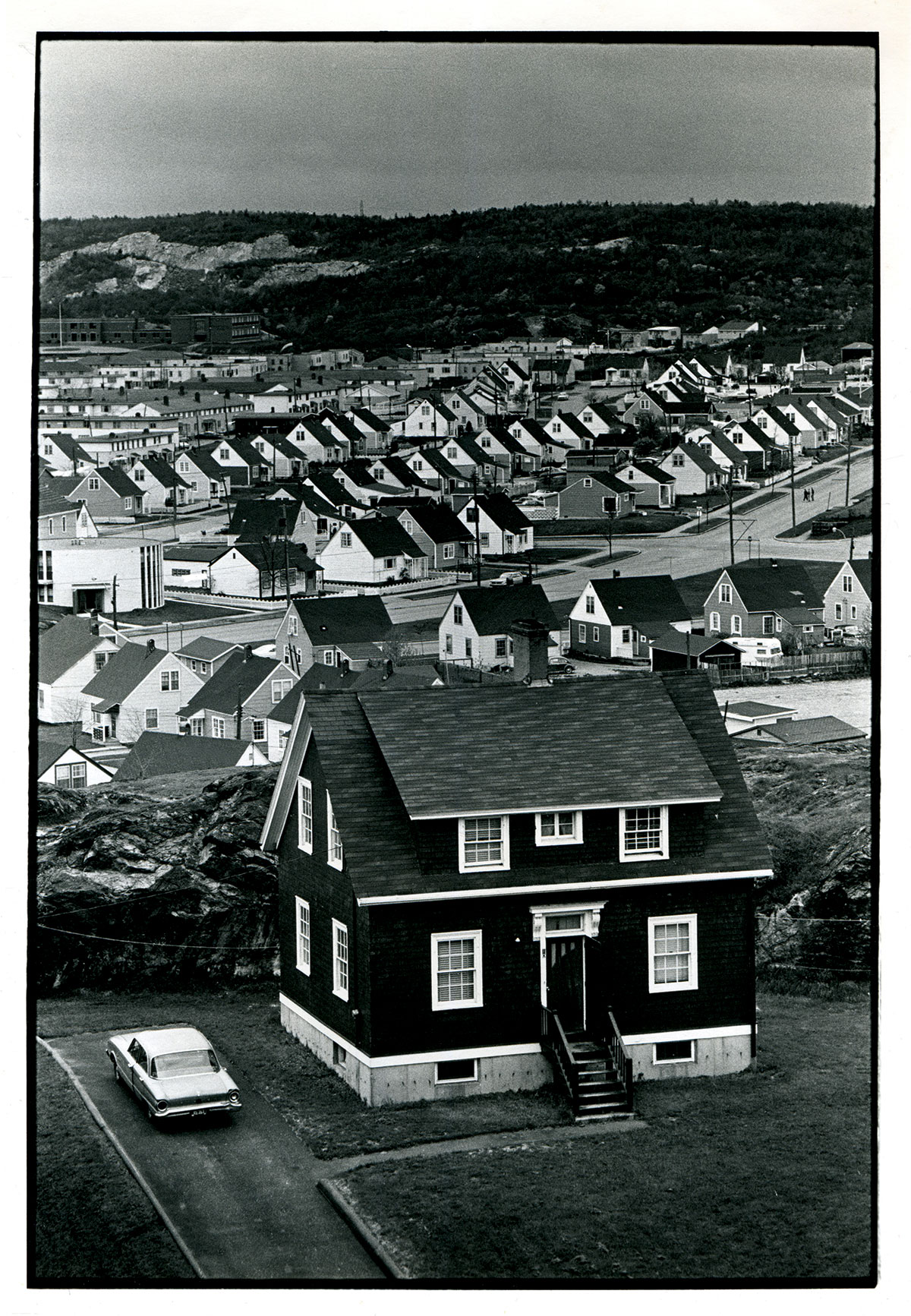

Portland Place (shown in 1968), Crescent Valley, and the Rifle Range were Saint John’s major post-war housing projects.

A Main Street backyard, near the uptown viaduct, 1964.

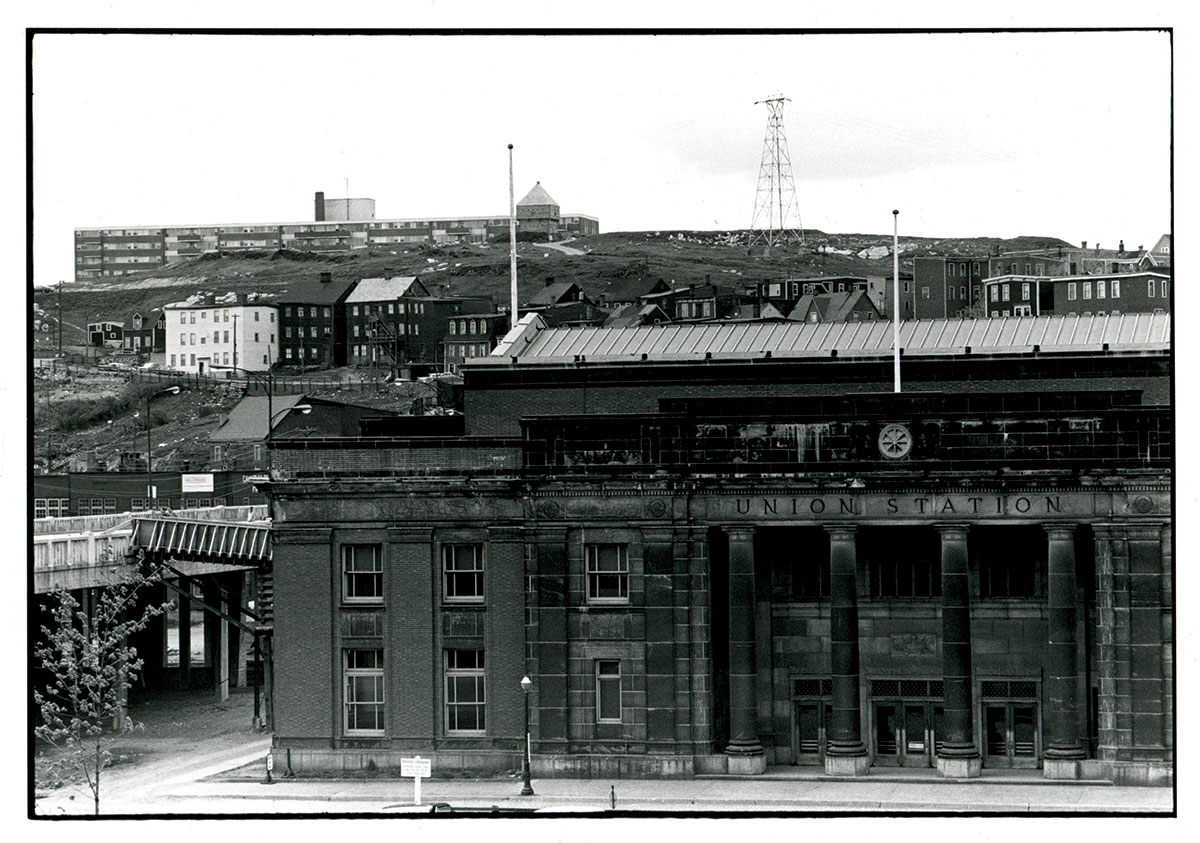

Built in 1933, Union Station (shown in 1968) was a major component of Canada’s railway system, having hosted King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on their 1939 royal tour. By 1973, its perceived viability had lessened and it was demolished. Fort Howe, the eighteenth-century British army fortification site, sits on the hill beyond.

Children play on the residential Moore Street in 1968.

King’s Square, looking west, in 1964. The neon sign of the Riviera can be seen in the background. The restaurant was destroyed in 1986 by a gas explosion.

Urban renewal at the foot of Union Street, 1968.

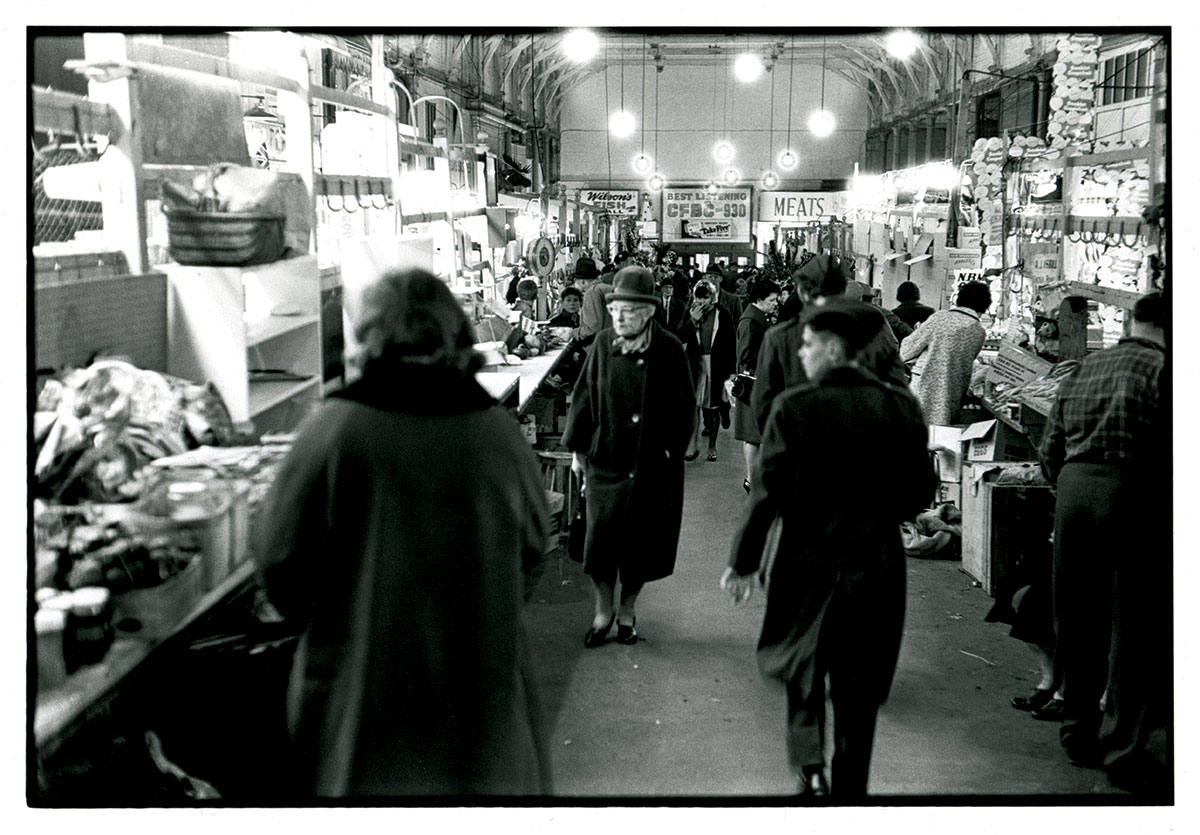

Built in 1876, the City Market (shown in 1965) survived Saint John’s Great Fire the following year. It is the oldest continuing farmer’s market in Canada.