Architect Wilfred Shulman promoted Sherwood Towers, 206 St. George Street, with a detailed model.

It was almost certainly Puccini, probably an aria from La Bohème, an opera about rent. Back and forth, two voices, a tenor and mezzo-soprano, jousted from open windows on the upper floors of separate apartment buildings in midtown Toronto—voices invisible in the dark and unable to see where, or who, the other was.1

The spontaneous, semipublic opera, lasting about twenty minutes, added a surprising note to the St. George Street cityscape on a hot August night in 1996. Yet, it was no more surprising, really, than a little bit of urban theatre that startled neighbours and passersby here one winter evening a year or two earlier.

Sometime after the dinner hour, midway along this apartment building row that rose in the fifties and sixties, between Bloor Street West and Dupont Street, the bigger-than-life image of a plucked, dressed chicken escaping from a kitchen range was projected across a laneway between two apartment blocks, seven floors up.

The screen was the white, glazed brick south wall of 177 St. George Street, and the film was Thanksgiving, a National Film Board of Canada 16-mm short in which a raw, headless poulet, animated with the aid of stop-action filming, flees on its drumsticks to safety.

A warning on the film can read “NOT FOR CHILDREN,” recalled the fine arts student—soon to study at Yale—who ran the projector for a gathering of friends from her glass-walled corner apartment opposite the movie, at 169 St. George Street.2

Not for children, indeed.

The exact same has been said about apartments themselves; one cliché among those accepted, repeated and generally believed in a North American culture infatuated, and in no small measure governed, by clichés—suburban homes, private cars, nuclear families, Republican politics. In this individualist universe, apartments, though creations of capital, have never quite fit.

“It is contended,” a contributor to Canadian Architect & Builder noted in the eighteen-nineties, summing up sentiments still heard today, “that there is no privacy in these great piles, no place for children, and that many other things are lacking to the man who considers his home is castle.”3

Not much would change. “THOSE NASTY APARTMENTS—AN OLD TORONTO PREJUDICE DIES HARD” flashed a headline over a story that appeared in the pages of the Toronto Star just past the middle of the twentieth century. “All over town, various politicians, planners and newspaper editorial writers are huddling their skirts about them and shrieking….”4

APARTMENTS THWART PASTORS said a newspaper report in the same era, in which a building superintendent claimed to be able to observe the shift in a person’s personality when they moved from a house into an apartment. “They withdraw into themselves, they don’t smile as often and seem to lose interest in other people.”5 The inherent irresponsibility of tenants seemed proved, definitively, one June day in 1963, when someone returning from a weekend outing stocked a new Toronto apartment building’s reflecting pool with live brook trout, fishing the creatures out by casting from his fifth floor balcony.6

Obviously more genuine, as concerns, were the misgivings of urban citizens in Toronto and elsewhere who, particularly in the post–Second World War era, simply found the world of apartment houses rising about them all too brave and new. Building shadows, the demolition of landmarks, and the hulking presence of big, new structures in leafy old neighbourhoods seemed a dramatic incursion on normal life—which it was.

The post-war era’s planning credo, meanwhile, had also raised a red flag over high density, establishing that congestion and crowding—and what but stacked houses and office buildings brought these?—were mortal enemies of “satisfactory living conditions”7in cities worldwide. Their mantra would pave the way (who would have guessed) for something less satisfactory—sprawl.8 No matter. “Some 150 ratepayers showed up at City Hall yesterday to knock down a proposed thirteen-storey apartment building planned for St. George Street,” the Star reported on July 31, 1963, after developer Nick Detoro proposed building on several lots straddling No. 191, halfway between Bloor and Dupont streets. “Reaction among our residents [to Detoro’s plans] has varied from shock to incredulity.”9

Grievances were real and imagined, and, it appears, perennial. From the eighteen-nineties to the nineteen-seventies they mirrored not only the understandable upset of residents of old neighbourhoods, but also an age-old bias toward ownership, a hushed anxiety about the sort of people who might not have enough money to buy, and a measure of hostility toward the often unfamiliar people and capital designing, building and backing the new projects.

Yet, behind the upset and prejudice lay a powerful fascination with the possibilities—architectural, social, economic and otherwise. “This was the city of homes,” one Toronto observer wrote in the nineteen-fifties, as new apartment buildings—despite zoning restrictions and Ontario Municipal Board hearings and such citizen protests as were possible at the time—marched up Jameson and Tyndall avenues in Parkdale, up St. George Street in the Annex and up upscale Avenue Road north of St. Clair Avenue West. “Now [Toronto] is becoming a city of apartments. Everywhere…huge piles of brick, with fancy doorways, panorama balconies and outsized windows, are rearing skywards. Toronto has a new breed of citizen—the cliff dweller.”10

At the University of Toronto, no less a city builder than Eric Arthur, the New Zealand–born professor of architecture whose later book, Toronto: No Mean City, would celebrate old buildings, was teaching his students how to build new ones—really new ones. One might record, adore and even build with the vocabulary of ancient Greece and Rome and Colonial America in 1950, but something else had come along that was conquering the world. It was the aptly-named International Style: “normative, universal and technically pure” in architects’ lingo,11 “glass boxes, no gingerbread” to the layperson, and to both—at least for a time—the most exciting event in architecture since the Acropolis.

The style’s champion, in Toronto, was Arthur, and if he seemed gruff and old and a bit mean to youths in U. of T.’s five-year architecture program,12 there was no mistaking his contempt was actually for the old guard in the city’s architecture business—the big firms, some operating under names of men by this time dead, that, after the war, had resumed doing pretty much what they had done before it. (The trend was surely epitomized by the Bank of Nova Scotia headquarters at King and Bay streets, a stepped-back, Jazz Age skyscraper designed in 1930 but built in 1949 to the plans of architect John Lyle, who died in 1945.)13

Arthur set out to install a new guard, via the classroom and a rigourous Modernist curriculum (among those he invited to visit U. of T. to speak to students were Walter Gropius, Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, Buckminster Fuller and Eero Saarinen), and sometimes his students paid a price. In the nineteen-fifties, despite the boom, it was no easy matter for young graduates to land a job in the “insurance school”—the big established firms like Marani & Morris or Mathers & Haldenby, who were hard at work on only vaguely modern brick piles for establishment clients like Confederation Life and Manulife. An Arthur-backed public protest by U. of T. architecture students against one such design can hardly have aided the cause of student employment after it helped kill, in 1953, a Marani proposal (already contracted to be built) for a new City Hall.14

Today, a list of students from U. of T.’s Arthur era—forty-three years from 1923 to 1966—reads itself like a who’s who of subsequent generations of name architects: Raymond Moriyama, John B. Parkin, Howard Chapman, James Murray, Charles Edward Pratt, George Boake, Jerome Markson, Irving Grossman, and George Hamann, to name some. But most started small, without apprenticeships in plush offices. Typically, they started out with the required field placement, often in a small, anonymous firm, then broke out on their own as soon as they could. “The established firms that were in business before the war tended to grab off all the big jobs,” remembers Leo Venchiarutti, who graduated from U. of T. in 1947.15 George Boake reminisced in 1999 about the launch of his partnership with James Crang in 1952: “We started out working in the basement of Jim’s father’s house on Regal Road. We very shortly thereafter bought a couple of [Victorian] houses on Huntley Street at Bloor, and converted these houses into office space.”16 The big firms? Well, “they were our competition!” Boake recalls today. He may be too kind, for while Toronto’s establishment architects had the richest clients and biggest commissions, Eric Arthur was probably right: they were, by the fifties, running out of ideas. Arthur’s students weren’t. Hungry for work, freshly minted to practice a new philosophy, they would connect with younger, brasher clients and new kinds of projects the big guys cared little about.

Architect George Boake at 169 St. George Street, September 20, 1999, his first visit in forty years.

Walk out onto St. George Street from the subway today, and a pleasant, urbane scene unfolds. Glance left and you see the York Club, “the most distinguished Richardsonian Romanesque house in Toronto,” 17 completed in 1889 for Toronto liquor king George Gooderham, and today sitting on a lush shaded lawn. Kitty-corner across Bloor Street West is Raymond Moriyama’s Bata Shoe Museum, its lid-like roof always seeming to be ajar over a building resembling a shoebox. Turn to walk north and you first see more Victorian-era mansions on the west side, dressed well in slate roofs and copper trim. But right away, above and beyond, on both sides of the street, your eye moves to apartment houses, between seven and twenty storeys tall, which continue intermittently up the few long blocks to Dupont Street. Most were built on single house lots formerly occupied by mansions, some of which, like No. 157 at the corner of Lowther Avenue and St. George, where Timothy’s son, E. Y. Eaton, once lived, remain between the newer buildings. (Many of these were men’s fraternities in 1999.) To this mix, as you stroll north, is added the First Church of Christ Scientist on the northwest corner of Lowther, with formal, classical columns and a broad lawn; the Chinese consulate south of Bernard Avenue, a Jack Diamond–designed building from the nineteen-seventies, red brick and set back; the presence of elms and maples (albeit thinning), whose crowns, at intervals, form a canopy over St. George; and, finally, before Dupont Street, more typically modest Toronto Annex homes.

Virtually all of the apartment buildings were designed by University of Toronto architecture graduates, many of them fresh out of school, testing their mettle at the new Modernism, and getting a fast dunk in the swashbuckling, non-establishment side of Toronto real estate. “The apartment business after the Second World War in Toronto was a gold mine for adventurers, newcomers in the field and fly-by-night entrepreneurs,” said one observer, looking back from the nineteen-sixties.18 George Boake found himself in the first two-thirds of such a grouping, when he and Jim Crang—both newcomers, and so, by default, adventurers—were hired to design 145 and 169 St. George. Their client was a man—well, really a youth, tall and lanky—named Peter Robinson, a principal with Keith Kingsley in Marshall Development Co., an entity that later vanished. “He was twenty or twenty-one years old, younger than either of us,” says Boake. “He wanted to go places in a hurry.”19

Wilfred Shulman, who graduated from U. of T. in 1943, linked up with his cousin, Leon Weinstein, to build Sherwood Tower at 206 St. George Street in 1954. One of the first high-rises on St. George, it mirrored, about half-and-half, Shulman’s strictly modernist beliefs as an architect, and Weinstein’s shrewd, and sometimes delightful, instincts as a marketing man.

Weinstein was the owner of Power supermarkets, an independent chain of grocery stores that would later be merged into Loblaws. Soon after investing in 206, Power would open a supermarket on Dupont Street, to serve what Weinstein’s architect cousin forecasted would soon be Toronto’s “second Park Avenue, second only to the towering posh apartments now going up on Avenue Road.”20

The pair had a toy-like replica of 206 made, which they had photographed, and they used the model and the pictures to promote the building. By chance or by design, the suppliers of materials for the building, such as the Hillsulate curtain-wall panels used on the front (and which Eric Arthur also specified on several projects), used pictures of 206 under construction in their own trade-journal advertisements.21

Sherwood Tower was modern architecture in its spare, economical epitome, a squared-off study in glass, brick and balconies.

“Did he ever design a Colonial house or a classical—”

“Never,” Shulman’s wife, Rhea, said in 1999.22

“It came as quite a shock to residents of St. George Street,” Shulman himself acknowledged in a newspaper interview, after 206 went up, and right about the time he moved his studio to a new office building nearby, at 99 Avenue Road, which he’d designed. “But it is inevitable more will be built there [St. George Street] because of its valuable location. Homes in that area are of the type which require servants. And since servants are hard to come by these days, it is possible many homeowners on the street would welcome a good offer for their property and move to a smaller place.”23

Weinstein’s supermarket would capitalize on his apartment house in uncanny ways. “A sign of the era’s trends in domestic architecture was a promotion [at Power on Dupont] for Delsey toilet paper (two roles for thirty-seven cents) in pink, blue, yellow and green—the colours of the bathroom tile and fixtures in the spanking new apartments on St. George Street.”24 Later, Shulman would try to launch an idea imported from Europe, “co-op” apartments that tenants owned. He designed 74 Spadina Road as a co-op, but, in an era before condominiums, Casa Loma Towers, which today stands on mosaic-tiled pillars that were a Shulman trademark, didn’t catch on.25

Looking back from twentieth century’s end at their mid-century creations, some of the buildings’ architects were candidly critical. “Most of them aren’t, you know, that good, from a purist architectural point of view,” said Venchiarutti, including in the critique his own mid-fifties buildings, the nine-storey Skyliner at 224 (named, perhaps, for the approaching jet age), and eight-storey St. George Towers at 214. “Well, maybe that one [224] for Cadillac [Cadillac Development, later Cadillac Fairview] wasn’t so bad.”

Besides cocky youngsters like Robinson (who somehow found Bronfman money for some of his projects),26 there were “owner-builders” like Venchiarutti’s Italian-born parents, who didn’t build on St. George, but from whom he inherited the genes to work with the likes of other enterprising Italian and Jewish families—entrepreneurs the likes of Andy Ucci, and Meyer Wise —who did. “An owner-builder would go out and grab a couple of houses on St. George Street, and get a rezoning,” said Venchiarutti. “You could build ten feet from the lot line; you could put a ten-storey building right up against some lady’s house in the Annex.” In this highly speculative environment, where someone might build simply to sell or hold forever to bequeath to grandchildren, professional fees were lower, budgets tighter, the architect less of a god. “It isn’t every architect that can understand how an owner-builder works,” Venchiarutti said in 1999. “It came to me naturally.”27

At times, on St. George Street, it is difficult to believe that the apartment buildings were designed at all. Just steps from the subway entrance, on the east side, between Prince Arthur and Lowther avenues, three virtually identical buildings at 149, 151 (once “the Trevi”) and 153 went up rapid-fire between 1959 and 1961. Featureless, rectangular slabs, they are carbon copies with three dimensions. Drawings on file in the city of Toronto property department suggest, indeed, that the same blueprints were recycled for each.28 The triumvirate is testimony to the spare efficiency of the office of Edward (Eddie) I. Richmond, a pre-war U. of T. architecture graduate who applied post-war minimalist principles with a particularly sharp pencil. Richmond was capable of better: up St. George, at the corner of Bernard Avenue, in 1958, he gave the Panoramic Apartments (whose street address is 88 Bernard) a spectacular, south-facing eleventh-floor roof garden (closed to tenants today), air-pressurized corridors to keep out cooking smells, and bright, airy apartments. Their layouts didn’t waste an inch, and the units, as the building’s name implied, offered views to die for when you pulled back their fashionable bamboo curtains.29

So it wasn’t art to many beholders. Was St. George Street’s “modern” housing even architecture? Not in the eyes of the widows and university professors of the nineteen-fifties Annex who protested all the construction, understandably, at the time; not to nineteen-seventies sensibilities when it was noted, tersely, that in the fifties “an unforeseen loophole led to the rapid construction of some high-density apartments on large lots.”30 And certainly not, to most people, at the millennium, a time of reaction and nostalgia when the public more readily understood the nineteenth century than the twentieth. It knew better the names of dead Victorian-era architects like Eden Smith and E. J. Lennox (creator of Old City Hall), whose mansions were the pride of the Annex Residents’ Association house tours.31 Hardly anybody gave a passing glance to the apartment buildings on St. George Street.

And yet, and yet. During the nineteen-nineties, a mysterious man could be seen, once in a while, standing on the sidewalk on the west side of St. George Street, looking across at the apartment building on the east side. Neatly, but casually, dressed, greying at the temples, he would gaze up at 169 St. George, a few hundred feet north of Lowther Avenue, appearing to examine the building. At least once he had someone else with him. They looked at the nine-storey apartment house, then turned to each other and talked, and looked again. It was obvious to people who lived at 169—and they did notice—that the man who visited occasionally wasn’t up to anything nefarious. He was admiring the architecture.32

That didn’t seem unusual to tenants, because they had come to admire the architecture themselves. If they knew nothing about Modernism or the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, whose artists perfected it; if they had never heard of Eric Arthur or the University of Toronto’s School of Architecture, much less its post-war graduates; if they never even thought apartment houses rentable to middle-class people like them needed to be designed by architects—well, even if these things were not part of their conscious, they did know what they liked.

“We used to look over here and see all this glass,” a seventh-floor tenant at 169, Margaret Oman, told a downstairs neighbour in 1998. Oman’s boyfriend had once lived at 177 St. George Street, the next building to the north. They used to sit in his apartment, looking across the parking laneway between the two buildings, beguiled by 169’s translucence—tenants’ red or turquoise walls, their shiny venetian blinds, their lamps sparkling through frosted glass panels in the balcony railing frames. “I said to Bill [Bill Shaver, soon her spouse] why are you living here? Why don’t you live over there? ”33

Since it was completed in 1958, 169 has had no other name—the legacy perhaps of that extra-youthful developer, Peter Robinson, who, if he was as sharp as architect George Boake remembers, might have known that in New York the smartest addresses are referred to by a shorthand—their numbers.34 Notwithstanding, after forty years of wear and tear, 169 probably did not appear quite as smart as it did, say, on October 3, 1958, when Modernism was high style and this advertisement appeared in the Toronto Star: “Brand New Deluxe Building. Only Two Short Blocks North Of Bloor Street. In Finest District, Designed For Particular People, Wall-to-Wall Windows, Large Inset Balconies, Huge Closets, Spectacular Roof Garden, Close To Everything, Only A Few Left, WA4-0813.”35

Stepping off the Bloor-Danforth streetcar at St. George that October day, an apartment hunter would have walked past the hoarding going up and holes going in for 149, whose ultra-plain plans Eddie Richmond, back in his office, may well have been duplicating for 151 and 153 on his Gestetner. They would walk past 145, also by Crang & Boake, but, compared to 169, a whale of a building, going up on the site where the gracious 1891 Prince Arthur House had stood just months before.

The apartment hunter would have crossed Lowther, and after a few steps more looked up through the elms and silver maples. Towering—by the standards of the day—stood nine storeys of, basically, glass in slim, stylish steel frames and casements; ribbons of transparency in turn framed by a slim, grid-like concrete structure, the whole floating lightly on stilts. Its address, 169 St. George, was spelled out sans serif over the entrance, which was itself a glass pavilion, leading into a lobby of plate-glass and glazed, speckled brick walls. On the ceiling in the lobby was a brass lamp, a sphere whose projecting spikes with little bulbs on the end made it look like a satellite or some subatomic particle.

“Everybody smoked!” said Alec Keefer in the late nineteen-nineties, perhaps aware that, in the lobby, holes next to the elevator once anchored a half moon, stainless-steel ashtray.

“Women in seamed nylons, the sound of high heels on terrazzo, dresses of Wedgewood blue—light turquoise,” Keefer exclaimed. “The clothes were like curtain walls! Cool, smooth, sophisticated, easy.”

One-sixty-nine was as glamourous and modern as tomorrow, and “Tomorrow was just this fabulous place that we were all dying to get to.”36

You’d go in a tiny elevator—push eight, why don’t you, to inspect one of those corner apartments, up high—“wanna see an ’02? ” asks the realtor. And you do. The key, brassy and bright, slides in, opening the door. The smell is of fresh paint, over fresh plaster, barely dry. You step onto the parquet floor, all light and blond and slippery under fresh wax, and you are pulled in by light spilling into the hallway. You walk straight in and then daylight tugs you to the left and—

“Wow.”

Afternoon sunlight floods a huge corner living room. Windowsills are barely above knee level.

“Look. There is not one exterior wall,” a resident would write years later. “Even at corners, the building’s support structure has been positioned outside on recessed balconies, so that the curtains of glass that enclose the living rooms can wrap right around the corners, unobstructed….The windows stretch to the ceiling, clear across every room, and into every corner.”37

The balcony door—three pieces of glass held in the slimmest of steel frames—is ajar on its hinges, and shifted slightly by a breath of October air. A great rock mass from another era—Casa Loma—rises on the ridge to the north, somewhere above the source of Taddle Creek; to that Iroquois Shoreline above Davenport Road spreads a carpet of treetops, whose fall colours are blazing in the sun.

You’ll take it.

“We thought there was an opportunity here,” remembered Boake, who with Jim Crang produced the design and drawings for 169 St. George Street.

The young architects had lucked into something valuable to an architect in swashbuckling Peter Robinson: a client who really didn’t much care what they did.

“There didn’t seem to be a lot of interference, if you like,” Boake said on September 20, 1999, and pleased with 169.“With this building we were able to do what we wanted to do.”

“One of the best small apartment buildings in Toronto,” Patricia McHugh would write in Toronto Architecture: A City Guide.

You, of course, wouldn’t have met Boake there that day when you rented your apartment in 1959, or for that matter for another forty years: after 169 was completed the architect wouldn’t return until 1999.

Like Rhea and Wilfred Shulman—the architect who designed the buildings whose curtain-walled upper floors were right across the St. George canyon from your place—you might have furnished your airy apartment with the latest, ultra-modern furniture lines. For instance with a sleek couch that stood on pencil-thin wrought-iron legs that Boake himself designed for Metalsmiths of Toronto and which won a National Industrial Design Award in 1953; or maybe, just like the Shulmans, you’d have gone for the chic, new Danish styles from J. & J. Brook, uptown on Avenue Road. Perhaps you’d have simply gone down to Simpson’s for a truckload of funky Russell Spanner. Or maybe, on a flush weekend, you’d have flown down to New York on a new turbo-prop Trans-Canada Airlines Viscount, and brought one of those featherweight Eames plastic-shell chairs back, checked—with a little fast talking—as your luggage.

Living in 169, with all its windows, you might have noticed, in Canadian Architect, an article titled “Translucence,” about glass-sheathed factories designed by Crang & Boake, not knowing they were the architects of your home. Years later you might have visited the Air Canada pavilion at Expo 67, not knowing it was designed by Crang & Boake, or shopped at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s new department store at Bloor and Yonge streets in the nineteen-seventies, or Holt Renfrew on Bloor Street in the nineteen-eighties—all Crang & Boake buildings. You might have noticed, but not made the connection, when a newspaper reported that a Toronto architectural firm, Crang & Boake, won runner-up in the French government’s worldwide competition to build La Defence in Paris.

Were you still living at 169 St. George in 1998, you might have fought a later property manager’s plan to shrink and block up the windows with thermal panes and opaque insulated panels. And you might have wept when, partially, it happened.

“When a building is built with some kind of love or truth in it, it kind of makes you feel that,” said one upset tenant. “And this building had that.”38

An “02” apartment at 169 St. George Street.

“Faludi! He didn’t influence my work at all!” exclaimed Uno Prii, the architect of 191 St. George Street, which went up in the sixties. But he did: Eugene Faludi, a Budapest-born planner who advised the city of Toronto, wrote a report, one of several, that from the late fifties to early sixties changed the rules for apartment building in Toronto and the Annex. The new rules were a response to public alarm and planners’ misgivings about the first wave of apartment houses that went up in Parkdale, on St. George Street and on Avenue Road.

“Taller buildings spaced further apart and with larger percentages of landscape areas can result in a better residential standard, even with a higher density,” Faludi wrote in 1963, in a dryly written, dryly named “Report on Apartment Building Development in East Annex Planning District,” prepared in his Church Street consulting office.39

Dry, but influential. Faludi’s philosophy mirrored the conventional wisdom of the day, which in retrospect seems rather anti-urban: it abhorred “high densities” and congested streets, assuming landscaped “green space”—in essence, absence of city—and emptiness were, well, the cat’s meow.

“Narrow buildings with limited spaces in between,” was how Faludi disparaged St. George Street’s nineteen-fifties apartment development. He recommended for the east Annex (that part of the neighbourhood east of Spadina Road) a system of “bonusing” that in the future would let developers build taller buildings—huge buildings you could enter on St. George and leave via Huron Street or Admiral Road—if they would compensate by leaving large landscaped lawn areas around them.

It is, today, a discredited philosophy; St. James Town, Regent Park and any number of horrific U.S. housing projects proved that people were more social, informal, city-loving animals than believed by number-, space- and ratio-obsessed “theoretical city planning,” as Jane Jacobs punningly referred to the era’s basic planning principles in The Death and Life of Great American Cities.40

But that is how Faludi, an autocrat, came to influence Prii, an artist.

Uno Prii, August 1999, with apartment houses he designed.

Prii, like the others who built on St. George Street and in the Annex, was a U. of T. architecture graduate (1955) and student of Eric Arthur. A top student, as a matter of fact; Arthur hired him summers to work in the office of Fleury & Arthur on Bloor Street East. Prii did, among other things, line drawings that appeared in No Mean City. Arthur was a Modernist, but as Prii sees it, his professor broke out of the box: “We have him to thank for the new City Hall,” the swoopy design by Finn Viljo Revell that was landed by international competition. Perhaps a taste for curves, and joyful flamboyance, ran in Baltic genes: Prii was born in Estonia, which shares its language with Finland. Baltic blood ran in the veins of Morris Lapidus, one of the twentieth century’s most flamboyant architects, designer of the extravagant Fontainebleu hotel in Miami Beach.

Prii probably designed more apartment buildings in the Annex than any other architect. Their addresses read like a list of places where everyone in Toronto, at one time or another, seems to have lived: 191 and 277 St. George, 11, 35, and 44 Walmer Road, 100 Spadina Road, 20 Prince Arthur, 485 Huron Street (the one with the rounded balconies).

Thanks to Faludi, whose influence found its way into city bylaws almost immediately, Prii’s buildings are large—20 Prince Arthur tops them out at twenty-three storeys—and stand remote from the street, surrounded, indeed, by lawns, landscaping and sometimes, as required by the era’s car-hugging planners, parking.

Thanks to Prii, with a nod to Lapidus,whom he admires, they are also distinctive—unmistakably original, freestanding, flowing sculptures, among those buildings whose functions, contrary to modernist doctrine, appear to follow their form. Indeed, Prii’s apartment buildings are a distinctly unsubtle protest against autocratic Modernism—the suburban Modernism of Faludi, the mechanical, automotive Modernism of Fred Gardiner (that’s his name on the expressway), the severe, squared-off, humourless Modernism of Mies van der Rohe.

“I got tired, eventually, of these straight boxes,” Prii said in 1999. “I thought, ‘let’s have a little fun. Why not create a different style that would make the buildings more interesting to people, and more appealing, and have their own life and character? ’ I was painting in my free time, doing some sculptures. So it became natural to me.”

Through the sixties, Prii had fun, using the new slip-form concrete molds which could slide up buildings, shaping them in concrete, almost as fast as you could pour the stuff in. Alternately, Prii engaged and alienated potential clients, pitching his sculptural ideas with passion and keeping a thick skin when prospects got up and walked away, which they sometimes did.41 Harry Hiller was one who didn’t. Polish-born, a carpenter by trade, he’d been fired from two jobs when he managed to buy a lot, build a bungalow and turn it over at a profit. For Hiller, who identified with Prii’s tastes and sensibilities, the architect would later design what he felt were his best buildings—11 and 44 Walmer Road and 20 Prince Arthur, with its massive flared base. “You know where I got this idea? The medieval cathedrals of Europe,” Prii said. “They’re flying buttresses,” which in fact reduced the need for wind bracing.

Prii gave 44 Walmer a fountain that looked like the curvy 1957 theme pavilion at Los Angeles International Airport. Thirty-five Walmer Road, “the Vincennes,” was given a soaring, curved canopy over its entrance, fins shooting out of the roof like Gemini rockets and a bronze sculpture of a woman in the lobby. It carried on a legacy of flamboyance that had preceded it, on this site, and seemed part of its soul, and architect Prii’s. For here had stood the Timothy Eaton mansion, “hung with art wallpaper and scattered with sentimental statuary, bits of interesting pottery and glass…”42 The description would have been apt for the architect’s own apartment on Bloor Street East, where in the nineties he lived in retirement with wife Silvia amid art created and collected for a lifetime.43

Of course, apartments as architecture and as businesses are separate concerns. Tenants’ relationship with the Hillers was not always smooth, particularly after rent controls ate into economic returns. Hillier’s wife “was something. She was fierce,” remembered Maria Gold, who lived at 35 Walmer Road in the nineteen-seventies. “She had a beehive, dyed-blond hairdo and wore high heels. She ran the place like it was her personal residence.”44 Said Marion Murray, who moved with her family to 35 Walmer in 1975, “She had flaws, but she liked children and hated cockroaches. Which meant that you would get rid of the cockroaches, and keep the kids.”45

Critics found the designs strange—“a long way from the beach,” a visitor from New York told the same Patricia McHugh who praised 169 St. George Street—and the apartment layouts conventional. Tenants felt fine. “We thought it a prettier building than most,” said Murray, who had also lived in apartment buildings at 59 Spadina Road (a Shulman), 267 St. George (probably a Richmond) and 15 and 50 Walmer Road. “My kids had a lawn to play on and a place to build snow forts in winter.”

So, like Lapidus in the U.S., Prii found himself more popular than acclaimed. “I never actually won a medal or any recognition from my fellow architects,” he said. “They thought my work just looked funny. ‘Why would Uno Prii do such a thing? ’ They didn’t like me. They didn’t like my work at all.” He didn’t care. “My designs are original,” said Prii. “And originality is the hardest thing to come by.”

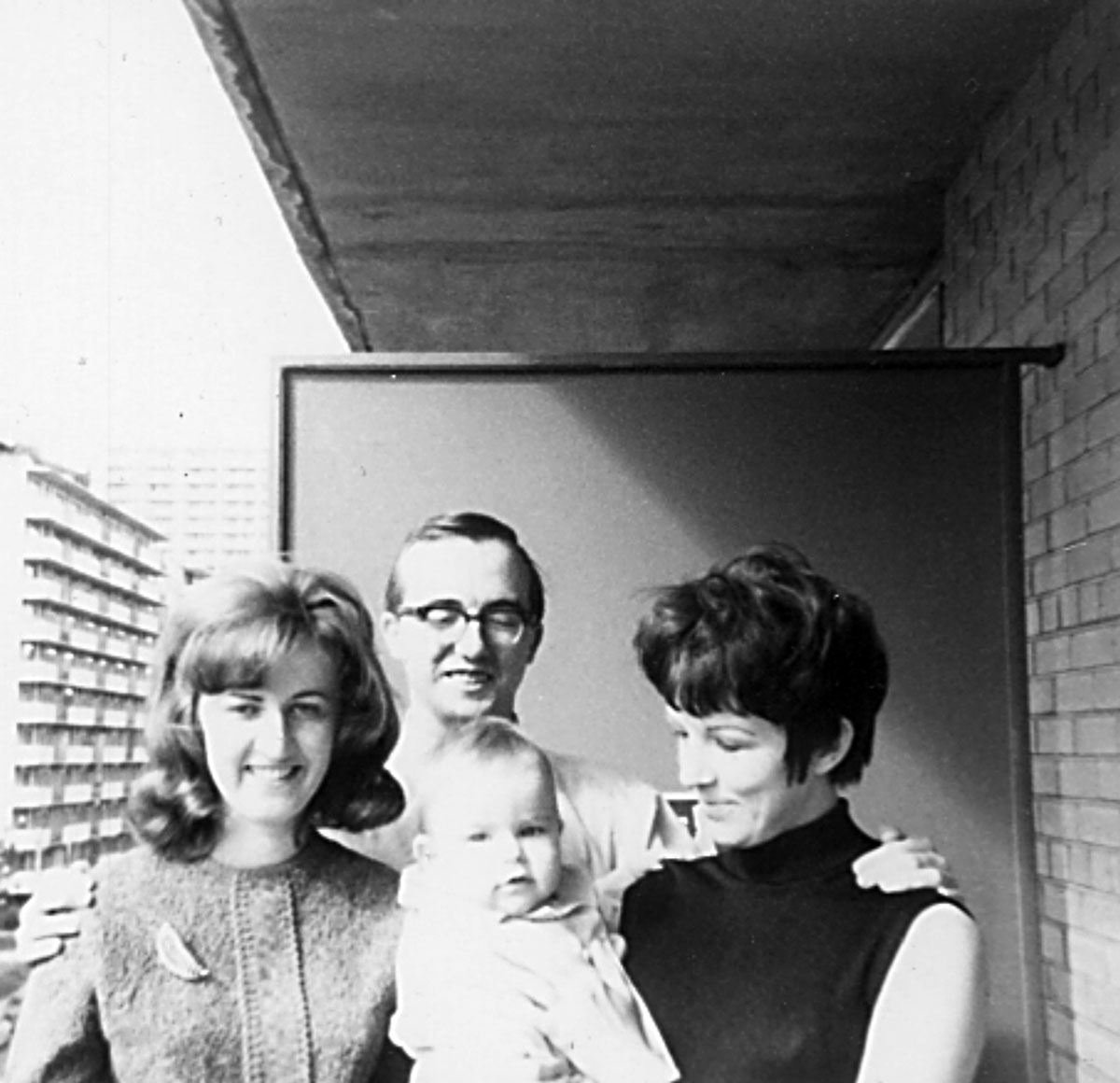

Family life at 59 Spadina Road in 1969.

The irony at the millennium is that all this mid-century architecture in midtown Toronto—developments the planners of the day decried, that the citizens feared would destroy—works so well. The recipe, in retrospect, is simple and classically Toronto: take a neighbourhood, and add to it, with a bit of this and a bit of that. Create space for people with different incomes, from different races and backgrounds; provide varying densities and building sizes and designs. Allow not only many options architecturally—always nice—but a powerful, overall dynamic. St. George Street, so fully and comfortably inhabited, is a busy avenue of people coming and going all day. Like the modern buildings that created it, it has its own beauty. The Annex, a neighbourhood still dominated by Victorian-era homes, now very pricey, is still home to thousands of regular people who can’t afford them, and are immeasurably richer for it.

This wealth is a legacy of young University of Toronto architecture graduates, two kinds of Modernism that today are hated and denigrated—boxes, poured concrete—and serendipity. It might not happen, if someone set out to do it today; it would be opposed, as it was then. The street, and Prii’s buildings scattered through the Annex, are instructive, not least for their ignored architecture, which had a certain unconscious integrity.

“The buildings are kind of light, they had lots of windows,” a young architecture scholar said about St. George Street, taking a fresh look in the nineteen-eighties. “They weren’t oppressive.”46

That is one of the loftiest things homes, and especially high-rise apartment houses, can aspire to.

It was achieved better on St. George Street by nineteen-fifties apartments than Victorian mansions; better on St. George Street by nineteen-fifties apartments than most nineteen-nineties condominiums with their glittering lobbies; better on St. George Street than strictly-planned St. James Town, Regent Park, and for that matter, luxurious, uptown Avenue Road. These buildings brought shelter, comfort, convenience and surprising theatre to thousands of people in a big city—ersatz opera on summer nights, a chicken escaping up a seventh floor wall. They are home for the Rodolfos and Minis of the twentieth century—ordinary folks who pay rent, and, like those in La Bohème, whose rich lives echo, literally, up and down the street.

Notes

- The soprano was Vancouver artist Carol Sawyer, who was a guest at 169 St. George Street. It is not known who the tenor was or where he was perched.

- Margaret Oman, then a film student at the Ontario College of Art, would later earn her master of fine arts at Yale.

- Harold Kalman, A History of Canadian Architecture, vol. 2 (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1994), 637.

- Ron Haggart, “Those Nasty Apartments—An Old Toronto Prejudice Dies Hard,” Toronto Star, June 26, 1962, p. 7.

- Ken Hull, “Tenant-elected Superintendents In High-rise Future,” Toronto Star, July 3, 1969, sec. A, p. 1.

- Richard Cole, “It’s Not Strictly For The Birds,” Toronto Telegram, June 26, 1963, p. 33. According to the Tely, the tenant fished the trout from the pool from his fifth-floor apartment.

- John Sewell, The Shape of the City (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 124.

- An early advocate of sprawl, though he hardly knew it, was architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose 1935 essay, “Broadacre City,” suggested cars and communications made concentrated cities unnecessary, and that people could live, more or less, in the country. Today, his model of a flat, spread out city criss-crossed by expressways looks, from a distance, like any modern regional suburb.

- “Ratepayers Sink New Development,” Toronto Star, July 31, 1963, p. 51.

- Lloyd Lockhart, “Once City of Homes, Apartments Give Toronto New Look,” Toronto Star, Sept. 20, 1958, p. 10.

- Leland Roth, A Concise History of American Architecture (New York: Harper & Row, 1980) 277.

- “I tried to keep away from him, a little,” Leo Venchiarutti told the author in 1999. Others said the same thing.

- William Dendy and William Kilbourn, Toronto Observed (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1986), 253.

- A worldwide architectural competition produced Viljo Revell’s design for new City Hall, completed in 1965. Jerome Markson, a 1953 architecture graduate, in 1998 remembered the Marani proposal as “a lump,” a “Mussolini-like monument that had nothing to do with the post-war idealism.”

- Leo Venchiarutti, phone conservation with author, July, 1999.

- George Boake, interview with author, September 20, 1999.

- Patricia McHugh, Toronto Architecture: A City Guide (Toronto: Mercury Books, 1985) 239.

- “Someone Lives In Mistakes of the Fast-dollar Era,” Globe & Mail, Feb. 18, 1964, p. 7.

- Boake, interview.

- Alex Henderson, Toronto Star, circa February, 1956.

- “Hills ‘Hillsulate’ Double-Glazed Units, Glass Curtain Walling and Coloured, Insulated Backing Panels Were Used in the Construciton of this Apartment Block at 206 St. George Street, Toronto.” Advertisement, Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal, 8, no. 2 (February, 1956): 8.

- Rhea Shulman, phone conservation with author, July, 1999.

- Henderson.

- Alfred Holden, “Never Walk Away From Your Customers,” Annex Gleaner, September, 1999, p. 13.

- Rhea Shulman to the author. See also, advertisement, “For Sale: Live for $28 to $48 a Month,” Toronto Telegram, November 1, 1957, p. 4; and Edwin Strachan, “Purchase Your Own Apartment,” Toronto Star, September 7, 1957, p. 7.

- Boake, interview.

- Venchiarutti, interview.

- Blueprints may be viewed on fiche in the City of Toronto department of buildings and inspections, nineteenth floor, east tower, City Hall.

- The author lived at 88 Bernard Avenue from 1981 to 1992.

- Jacob Spelt, Toronto (Don Mills: Collier-Macmillan Canada Ltd., 1973), 115.

- Alfred Holden, “When The Private Becomes Public,” Annex Gleaner, May, 1997, p. 24.

- Observed from 1992 to 1997 by author and others.

- Alfred Holden “A Good Building’s Grotesque Transformation,” Annex Gleaner, November 1998, p. 13.

- Paul Goldberger writes, “834 and 740 and 101…mean 834 Fifth Avenue, 740 Park Avenue, and 101 Central Park West.” Paul Goldberger, “A Touch Of Crass,” New Yorker, August 16, 1999, 87.

- Advertisement in Toronto Star, October 3, 1958, p. 41. The “WA” refers to the downtown Toronto “WAlnut” (92) telephone exchange; naming exchanges made numbers easier to remember, but phone companies soon ran out of number-letter combinations that could form words. In 1999, most tenants at 169 were still “92s.”

- Alec Keefer (former president of the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario) interview with author, April, 1999.

- Alfred Holden, “Diamond In The Rough,” Annex Gleaner, March, 1996, p. 16.

- The tenant was Claire Barclay. Interview with author, September, 1998.

- Eugene Faludi, Report on Apartment Building Development in East Annex Planning District, E. G. Faludi and Associates, Town Planning Consultants Limited, 1963, p. 3.

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), 12.

- Uno Prii, interview with author, April, 1999.

- William Dendy, Lost Toronto (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1978), 172-175.

- Uno Prii, interview with author, August, 1999.

- Maria Gold, interview with author, April, 1999.

- Marion Murray, interview with author, August, 1999.

- Adele Freedman, “Is There No Home Sweet Home In an Up-to-date Subdivision?” Globe & Mail, Dec. 11, 1988, sec. C, p. 13.