The sun had begun to set, but still his wife carried on. Andrews sulked in his backyard and poked at a clump of crabgrass with the toe of his slipper. He derived a perverse pleasure from his otherwise unblemished lawn. It had been touch and go for a few years in the late eighties. The children had been lax in the training of the family dog, but he had put an end to that by installing a patch of gravel at the side of the house, below the eaves, where the dog was confined twice daily by means of a short lead tied to a stake in the ground. Once the dog had thoroughly relieved itself on the gravel under Andrews’ watchful eye, it was released and permitted the run of the yard without posing any risk to the lawn.

His next-door neighbour, Domingas, liked to watch the whole production over the fence with an amused look, and say, “You’ve got it all under control, don’t you, boss? ”

Andrews would give a curt nod, proud of his ingenuity, but not wanting to appear so.

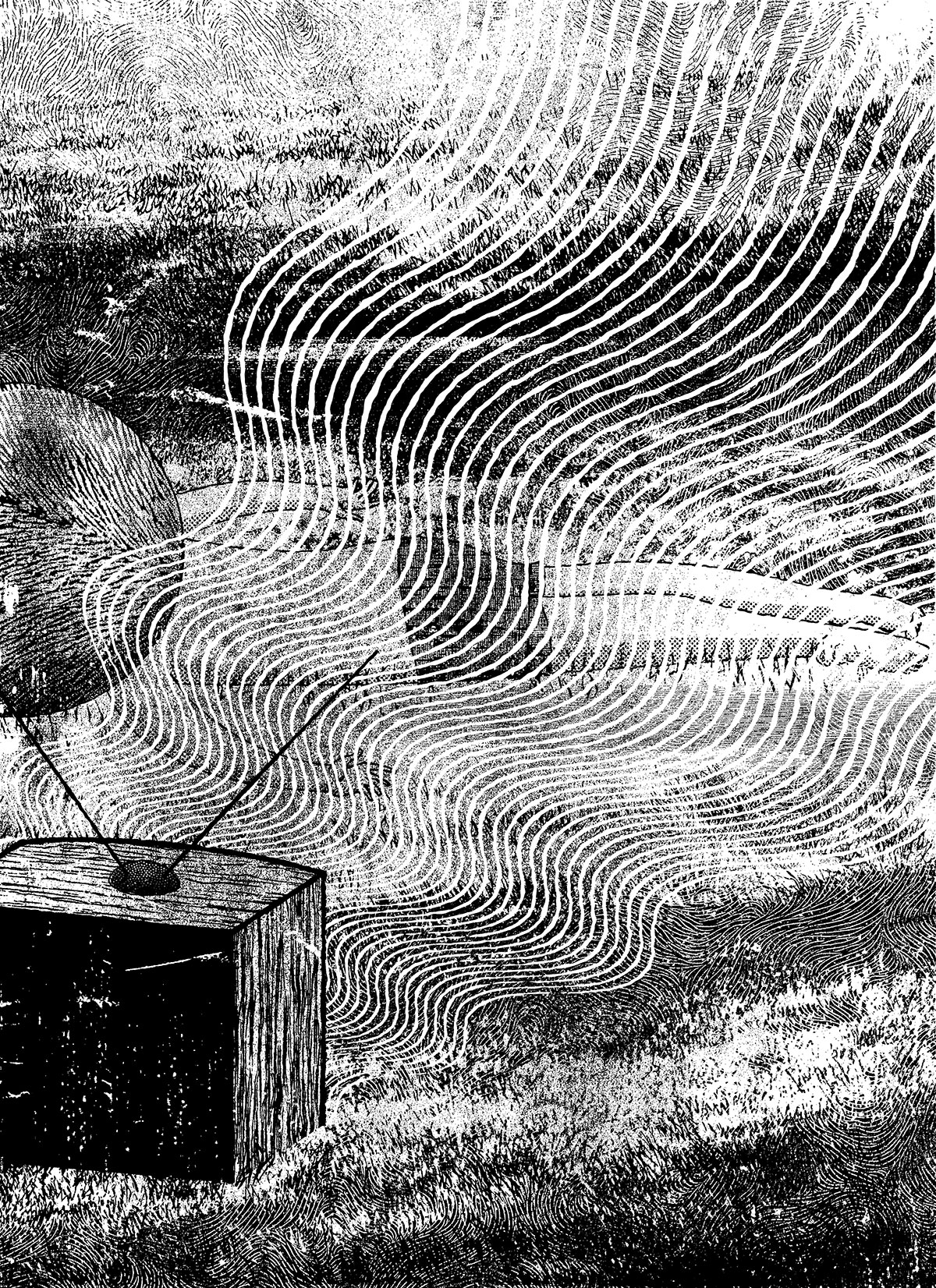

Now, beneath the deepening lilac of a suburban twilight, his lawn served as a salve for his nerves, which had been left raw by the wailing of his wife, Maureen, who sat glued to the television watching the CBC’s coverage of what appeared to be the sudden and—according to Maureen—globally devastating death of Princess Diana. A glance over his shoulder through the family room window reassured Andrews that he was better off in the yard, despite the growing darkness. Maureen was perched on the edge of the sofa, sodden tissue clutched in one hand and the phone receiver in the other, while the light of the television shone on her wet cheeks. Maureen’s lap cradled Delphinium, her indignant blue-point Siamese. Watching his wife of twenty-nine years wail into the phone at God-knows-who about the death of a woman she’d never met, and for whom she’d shown minimal interest over the years, Andrews felt a stirring within him that signalled despair. It felt as though there were a drain deep inside of him that would empty him out into a bewildering nothingness from which there would be no return. And so, when Andrews heard the hum of the garage-door opener, he beat a path across his lawn and through the side gate to greet and be distracted by whichever of his children had arrived home from wherever it was they’d gone.

Out front of the house, Andrews stood smiling behind the bent rear bumper of his car as his son, Charles, manoeuvred it into the garage. Charles braked when the windshield was just shy of the tennis ball Andrews had suspended from the ceiling on a length of twine for Maureen.

“It’s not my fault I can’t see over the hood,” she’d snapped at him on the day they’d learned the sensors on the automatic garage-door opener were not as sensitive to obstructions as they’d been led to believe.

Andrews had sucked on his toothpick and searched within himself for an appropriate response to the situation. One side of his rear bumper hung from the car by a bent piece of metal. The other side rested on the concrete floor. They’d been unable to reverse the closing door once it had knocked off Andrews’ bumper, so it was stuck at knee level.

“My car,” Andrews had finally said.

“Your car? ” said Maureen. “That could have been my head! Think about that!”

Andrews thought about it.

“I’ve got to call Rita,” Maureen had said, as she shuffled around the car and past Andrews to the door that led into the house. “She’s not going to believe this. I could have been killed.”

The door slammed shut behind Maureen. A few minutes passed, and then the light on the automatic door opener had flicked off, leaving Andrews in the dark, his calves bathed in the orange glow of the street light out front.

Andrews pulled his gaze up from the reattached bumper and watched Charles slide effortlessly out of the car door and swing it shut behind him in one fluid motion. There was no popping of joints, no groaning as he lifted his weight up and out, and no sign of exertion. Andrews felt proud, as though this physical ease was something Charles had learned from him, although he knew very well that wasn’t the case. Andrews had never been fluid at anything.

Charles saw his father standing behind the car.

“Hey,” he said nonchalantly and made for the door.

“I wouldn’t go in there if I were you,” said Andrews.

Charles paused on the step and turned to face his father with a weary expression.

“Your mother’s in there having a bird over some car accident.”

“You mean Princess Di? ” Charles’ face came to life. “Are they showing pictures of it? ” He turned and disappeared into the house.

“People die in car accidents every day!” Andrews called as the door slammed shut behind Charles. “Every day,” he muttered to himself.

Andrews sighed and looked down the street, knowing that any number of people could be watching him from behind their sheers. He knew this because when he wasn’t tending to his lawn, he spent much of his time watching his neighbours from behind his own expanse of sheers. He enjoyed this secret knowledge as each neighbour pulled up in a car that revealed his or her shortcomings. Rust marks, bald tires, filthy windows, crudely plagiarized handicap signs, and dashboards obscured by outdated parking tickets. Rear windows crammed with bleached-out tissue boxes, stuffed animals, stained pillows, and abandoned action figures. None of it surprised Andrews in light of the deplorable state of their lawns.

Of particular significance on his mental scale of poor car hygiene was Domingas, who had to park his dilapidated foreign car in the driveway because his garage was filled with his wife Rita’s wholesale beauty-supply inventory. Domingas apparently didn’t mind Rita’s annexing of the garage with her reeking pink boxes. Rather, when Andrews had teased him about it, Domingas said he was proud of his wife’s entrepreneurial spirit. This was driven home on Saturday mornings when Andrews’s station behind the sheers was more often than not blighted by a showy exchange between the couple after they’d loaded up the trunk of the car with pink boxes. Domingas would kiss Rita on her cheek before she got into the car, and as Rita reversed down the driveway, she would flutter her fingers through the windshield at Domingas. Domingas would then kiss the fingers of his hand and flutter them back at Rita.

The only thing more disturbing to Andrews than this public display of affection was his fear that Maureen would one day catch sight of the Saturday Morning Domingas Ritual. Not only would she erroneously conclude that he enjoyed watching other people’s private moments through the sheers, but in her quest to turn her life in to a carbon copy of everyone else’s, Maureen would very likely demand that Andrews also begin fluttering his fingers at her in public.

The thought made Andrews shiver, and he surfaced out of his reverie to find that he was still standing in the doorway of his garage, clad only in his housecoat and slippers. He smacked his palm against the garage-door opener, ducked out of the garage beneath the lowering door, and returned to the privacy of his backyard.

Andrews eyed the wooden bench Maureen had forced him to place at a ridiculous angle against the back corner of their fence. He never sat there because from that perspective, one could see all the rear bedroom windows of the houses on either side of his, and he would therefore feel as though he was on display. He tended instead to stick close to the deck that ran beneath the kitchen and living-room windows. But it was almost completely dark now, and the wooden bench looked more comfortable than the ornate wrought iron furniture Maureen had purchased for the patio, so Andrews wandered over and sat down.

“I don’t see what all the fuss is about.”

The voice echoed his thoughts, but was not his, and Andrews jerked his head up and around to find Domingas glaring over the fence toward the light of Andrews’ family room window.

“Domingas! You scared me.”

“It’s not like she’d have thought twice about that woman a day ago when she was still alive.”

Andrews watched with incredulity as Domingas jutted his chin at Andrews’ window.

“Ask me, that woman needs a hobby or something. Keep her mind engaged.” Although he was in complete agreement with Domingas, Andrews knew a line had been crossed, but the obligation to defend Maureen’s honour made him uneasy. The hypocrisy would be difficult to swallow.

“Come again? ” he said.

“Look at that,” Domingas said. “You’d think absolutely nothing in the world could have hit closer to home.”

Andrews reluctantly swiveled around on his bench to peer through his window, and saw that Maureen had been joined on the couch by Rita Domingas. The pair sat dabbing at their eyes with tissue from the box positioned on the sofa between them. Andrews’s relief at his misunderstanding was so immediate he was afraid he’d whimpered out loud. He glanced back at Domingas. Domingas was scowling at the window.

“At least your wife’s parents are British,” Andrews said. He rummaged in the pocket of his housecoat for a jujube he recalled leaving in there earlier.

“What’s that got to do with it? ”

“You’d think Maureen was a direct descendant the way she’s carrying on. Jujube? ” He held out a lint-encrusted candy toward Domingas.

“No thanks.”

“But she’s Canadian for three generations back,” Andrews continued as he picked fluff from his candy. “And before that, Irish. Irish Catholic, even.” They fell silent, Domingas scraping the palm of his hand up and down the scruff on his cheek, Andrews chewing thoughtfully on his jujube.

“Your lawn’s looking fine, boss,” said Domingas.

“There’s some crabgrass over there by the air-conditioning fan. I’ll have to get at it in the morning before it spreads.”

“Thing is, Rita hasn’t let me touch her in six years.”

Andrews choked on his jujube and tried to be subtle as he wretched into the palm of his hand.

Domingas continued. “We used to be at it all hours of the night and day when we were trying to have kids, but when we gave up on that, she gave up on everything.”

A light went on in Andrews’ kitchen window. He felt inexplicably saved. After a moment they heard an electric whirring noise.

“Maureen,” said Andrews. “She’s into the daiquiris.”

“That wholesale gig was the best thing that ever happened to me. Rita leaves the house every Saturday morning and then I’m free until one. I’ve met someone, Andrews.”

Andrews turned to stare slack-jawed at Domingas, his wet jujube still cupped in the palm of his hand. Out of the corner of his eye he saw the kitchen light go off. He felt abandoned, adrift, caught in a riptide of Domingas’s deception. “I wonder how long two people can go on living like this,” Domingas said. Andrews remembered his jujube. He carefully put it back into his mouth and then wiped the palm of his hand on his housecoat.

“How old’s your boy now, Andrews? Seventeen? ”

“That’s right,” Andrews said, wary.

“I bet it never occurs to him that he could end up like this.”

“Like what? ”

Domingas scratched at his whiskers and then sighed. “Never mind,” he said.

“Anyway, I’m leaving. Tonight. Rita doesn’t know yet. Just thought I’d say goodbye.”

“You’re kidding,” said Andrews, stunned.

“Take care, boss,” said Domingas, and then he walked away.

“Sure. I mean, you too.”

As he listened to his neighbour’s footfalls fade away, Andrews gazed up at the window of Charles’s bedroom. It was dark but for the erratic blue light of the television. In the living room, Maureen sat back in the sofa, legs crossed. She sipped a daiquiri and cackled with Rita, while the footage that had moments ago rendered her psychotic with grief went unnoticed. As he sat there contemplating the lacklustre Saturday mornings of his near future, it slowly dawned on Andrews that the contrived and empty gestures of another man’s dead marriage had been the only source of intimacy in his adult life. He would miss them. He would miss them like he missed every other illusion that had once sustained him: the meaningfulness of life, the institution of marriage, and the consolation of having had children. Andrews realized that when Domingas had wondered aloud how two people could live like this, he’d been referring to them—to Domingas and Andrews.

In the backyard, Andrews removed his housecoat and folded it neatly on the bench beside him. Then, with some effort, he lowered himself, groaning and wincing, first on to his knees and then his belly, so that he was lying face down in cool, damp grass. It was prickly against his cheek, but he didn’t mind. He ran his fingers back and forth though the springy turf, and deeply breathed in its earthy scent. It was the scent of final destinations—something Andrews had not yet lost faith in. He closed his eyes and steeled himself as best he could, determined, as he was, to stay the course.