The house located at 189 North Avenue, in Burlington, Vermont, is what is known as a four-square. Built in 1911, it is a two-storey cube, unpretentious but commodious, capped by a lofty pyramid—a tall hipped roof, punctuated on the four steep slopes by dormer windows. Instead of a point at the very top, a brick chimney rises forcefully near the middle of the house, through the attic’s muscular framing, which supports a heavy slate roof, and out to a high, blunt perch where pigeons like to gather.

“It’s sort of squire-like, being able to look down on your neighbours from up here,” my friend David Barber said to me when we visited the house, on August 1, 2005. The surrounding working-class neighbourhood, where my mother and grandfather grew up, sits on a high bluff, and from the west dormer of the house there are glimpses, through trees and over house tops, of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains, in New York state, to the west.

During the afternoon, thunderclouds rolled up the lake from the south. Because the attic gets hot in summer, the dormers are left open. When the rain came, you could hear the downpour, muffled by the slate. Members of my family have been living here since 1922, the current residents being my parents, Clem and Sylvia Holden. It’s fair to say the house has a Tut’s-tomb aspect to it. Treasures and trash lie indiscriminately about, one ever-morphing into the other. In the attic, under a drop cloth, a box containing a run of the first year of Fortune magazine. Over there, a shelf of Upton Sinclair novels. There’s technology: Garrard, Lenco, and Webcor turntables, from the days of hi-fi; an operable history of Bell telephones since about 1910; movie and slide projectors that still do service at Christmas and during summer vacations. An early Eames moulded-plywood chair sits under another cloth, while near it is a box of clay my uncle Buz used to sculpt model-car entries for the General Motors Fisher Body contest. For a long time there was even an Eclipse mattress up here with a tag that read, “AS APPROVED FOR THE USE OF THE DIONNE QUINTUPLETS.”

To one side, under some plastic sheeting, are toys, mostly vintage building sets. There is a heavy box of stone Anchor Blocks, from our ancestral Germany, played with by generations of children, and remnants of my brother Jeffrey’s Kenner Sky Rail, including a box top picturing the suspended vehicle, the one I remember weaving its way around futuristic towers we built during the 1963 Christmas season. Also here are some Tri-ang train sets—a C.N. freight, Canadian Pacific’s Canadian, with its dome car—and my Lego Town Plan. A measure of my skill as a lobbyist before Christmas of 1966 was its price: $27.50 (about one hundred and seventy 2006 dollars). “For Xmas Alfred,” I wrote brazenly on a Lego brochure, part of a substantial campaign resulting, arguably, in the biggest coup of my childhood.

But, on this rainy summer day, we were focused on something else. In a corner, David and I located large cardboard boxes, six or eight of them, dusty with coal soot from a notorious, now-defunct waterfront power plant. They were light for their size, as though there wasn’t much in them, and tightly sealed with tape. I’d promised David, a kindred spirit, that within these boxes was something of an Atlantis—the great, lost metropolis of a vanished civilization.

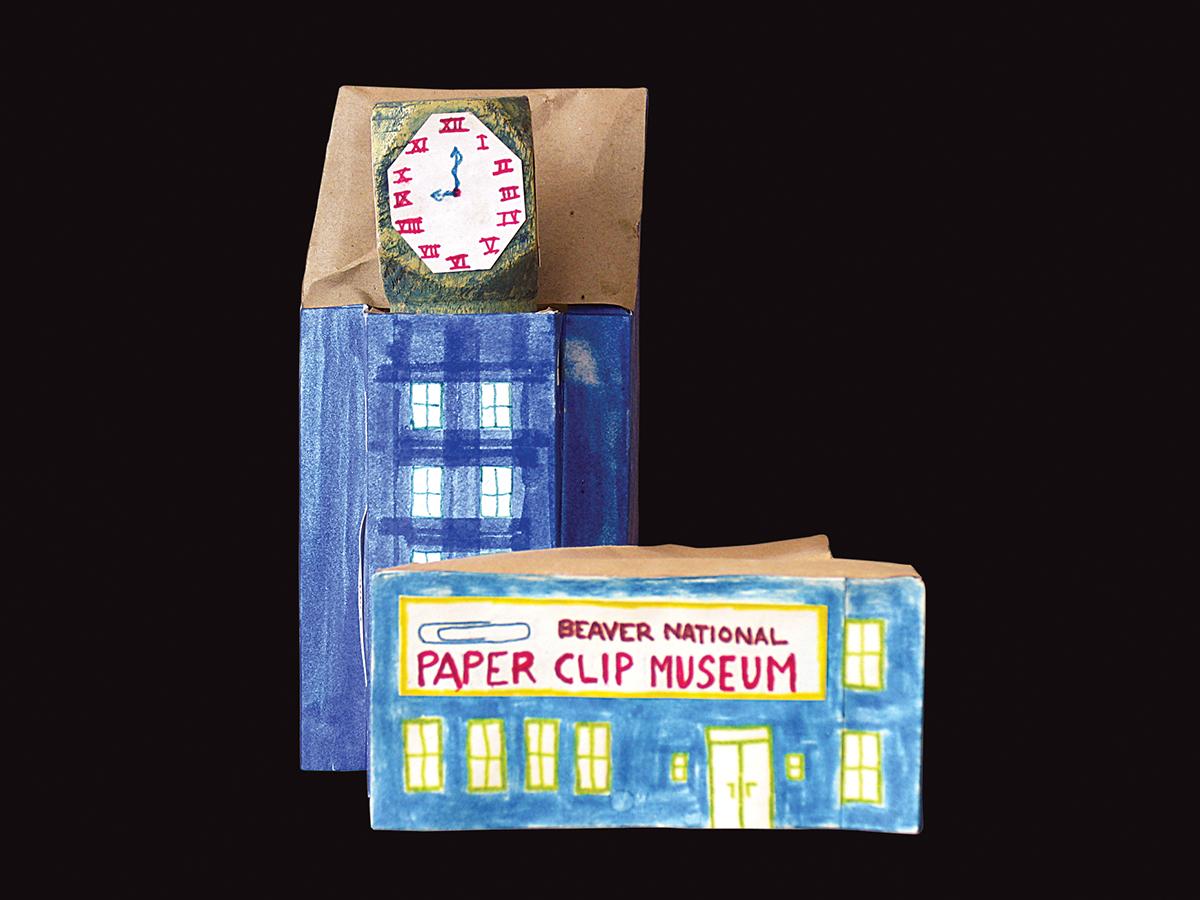

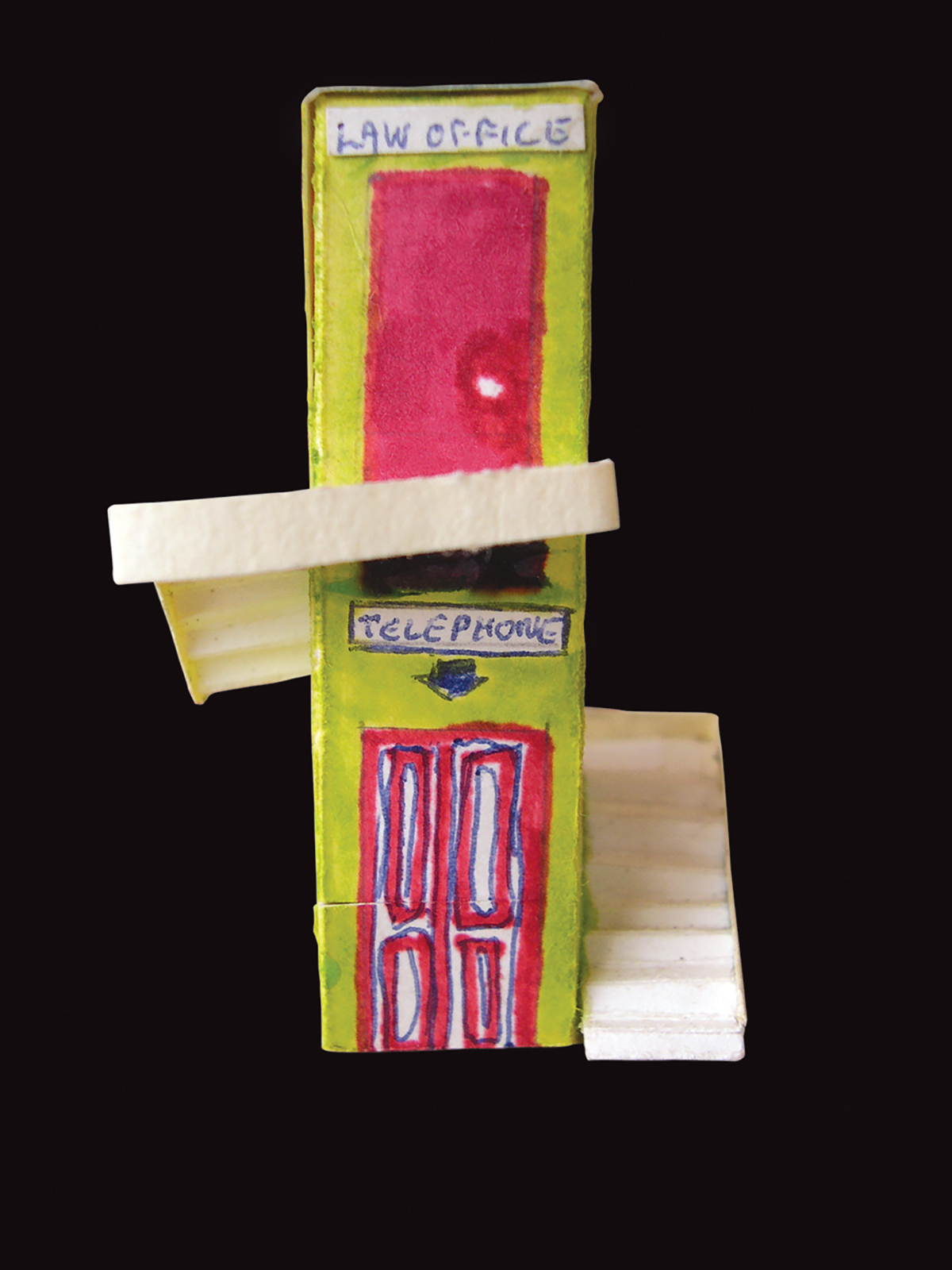

Time machines are the stuff of fiction, but time capsules turn up everywhere. A famous one is the Westinghouse time capsule, placed at the site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, not to be opened until the year 6939. More common are the accidental time capsules—the forgotten drawer, the back of a closet. Cardboard boxes aren’t the best material for making time capsules, but they served well in our watertight attic, as David and I discovered upon opening them. Inside were hundreds of handmade paper and cardboard buildings—a whole model city, as it had been packed and left nearly thirty years ago. Victorian, modernist, square, round, quadrilateral, short, tall, ordinary, and a few extraordinary, they were nested within each other such that, as they were being emptied, the contents of each box seemed to grow exponentially. Soon, the floor was filled with urban structures ranging from telephone booths to skyscrapers several feet high.

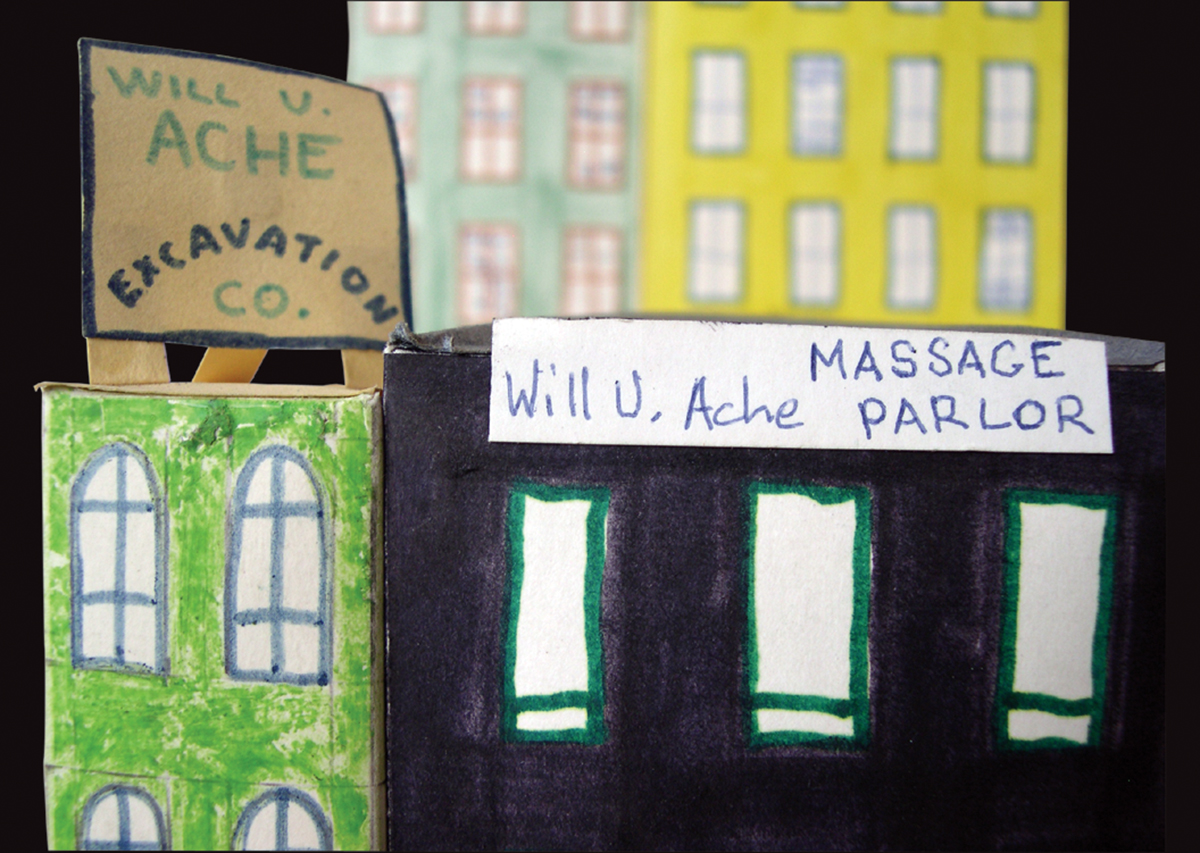

“Were you out of your minds? ” David asked, as the buildings piled up, knowing just a little of the history of how, as children, my brother, cousins, and I built this tiny town, bit by bit, summer by summer. He noted the human labour represented, the sheer number of buildings, and, on closer inspection, signs of the bizarre civilization that inhabited them. This cardboard city was, on many levels, a community of signs, figurative and literal, with much of its content improbable, silly, macabre, and cuttingly satirical.

The Shady Finance Company, we saw, was a tidy, three-storey business block with a shed roof. Martin Nock offered his wares at Fire-Trap Mobile Homes & Vampire Supplies. At Shody Protection and Security, a small sign on the back door read, “WALK RIGHT IN.” Towmaine’s Restaurant (“LIVING ENTERTAINMENT”) occupied the same building as Dr. Corpse, M.D., the municipal morgue, and Hal’s Auto City (indicated in a fourth-floor window). A sign over one four-storey business block read, “Grace Smedley, Precision Tricycles.” (That one I built myself, I could see by the coded dates we took to writing on our structures as we built them, in this case: “ACH 30/7/76.”) A law office occupied space above a phone booth, reached by exterior stairs. Good Housebreaking Magazine (“Journal of Professional Burglary”) took up residence in a pink business block with bars on the windows. Swipe! Magazine offered a competing vision of the trade from its own four-storey block across town.

Most of the buildings were free-standing, custom-created to fit a particular spot on our city’s map, such that the whole went together like a three-dimensional puzzle. No building is known to have gone astray, although the key map indicating exactly how everything fits together has, so a puzzle it truly is.

At a glance, this was a city of small business and endlessly gothy, arguably healthy, irreverence (partially inspired by a compilation of Charles Addams cartoons found on the camp bookshelf). Funeral homes such as Diemart (“DISCOUNT FUNERALS”) were numerous, as though people could hardly wait to go, while Count Alucard’s Fright Club, its offerings to the public vague, was designed by my cousin Lynn Sawyer in a style of dungeon adapted to Main Street—entry through a guillotine-like contraption of bars.

Main Street, Everytown, appeared to be the model from which this city grew, a community of tightly packed business blocks rising from the efforts and enterprises of its citizens—some good, such as Otto Flatte (musical supplies) and G. J. Blight (tree surgeon), some questionable, such as Bill Bogus (printer of bank notes), and Pierre DeCline (stockbroker). One of the more active small-business owners—at least by count of the many matchbox-sized properties on which his name appeared—was Ned Erp, whose storefront portfolio included Erp’s Dirt & Dust, Ned’s Erpburger, Erp’s Discount Horse Entrails, Erp’s Brand Name Junk, Erp’s Discount Rocks, and Erp’s 7-Day Old Discount Fish Shop.

On emptying the boxes, it became clear that, like the real world, a handful of large corporations and dominant families ran this city. J. Milford Squigley held fort in his “multi-national headquarters,” a nineteen-sixties–era Le Corbusier–style podium, with its second-storey overhanging the first. Its twin towers simultaneously reflected the shape of the era’s Quaker Oats box (from which they were made), and the brutalist style then in vogue. Squigley seems to have had his fingers in a department store, discount accordions, and a Squigley’s Diner, whose menu, if you trust the specials listed in the window, included yak eyes and giraffe steaks. (On another corner, Geoff’s Giraffes, a pet shop, sold the live article.)

An also-ran family, the Nosdurs, headquartered its cabal in an orange eleven-storey building whose tower was just one window wide. They positioned themselves as rivals of the Rudsons (their name was even Rudson spelled backward), but the real rivalry in this city—and the region—was between the Rudsons, whose many members had their fingers in businesses both big and small, and one Grace L. Ferguson, who, according to the 1960 Bob Newhart comedy skit she was stolen from, ran an airline and storm-door company. As on Newhart’s LP, here she was cast as a grasping, greedy Leona Helmsley type. Headquarters for the airline division, a deliberately bare-bones operation, was a tiny, two-storey, two-window-wide purple and orange box. But Ferguson’s corporate headquarters was one of the tallest, most imposing buildings in town—a soaring, slim red cardboard edifice, its modernist tower with just three sides.

The Ferguson tower contrasted with the Rudson empire’s stepped-back skyscraper, three feet tall and reminiscently Empire State Building–ish. Nominal head of the family was Bunkabard (Bunky) Rudson, a buffoonish young man who drove an olive-coloured Oldsmobile (the town was fully inhabited by miniature Matchbox toy cars and their ilk). The Rudsons had interests in everything from airlines to outboard motors (“Everude”) to fast food, including Rudson Peanut Butter and Jelly Sandwiches, a one-storey building with two pieces of bread floating over its roof, layers of brown and red felt acting as the filling.

In comparison to the post-9/11 era, the nineteen-seventies seems like an age of innocence. But we were reminded by these playful, homemade artifacts that no, it wasn’t. Elections shaped this fantasy town and so, ultimately, did real-world events. The egotistical Bunky was also a political figure, faintly modelled on U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy, who also drove an Oldsmobile. On one of the Rudson family enterprise’s buildings is the painted sign: “BUNKY FOR KING” (the years ’48, ’52, ’56, ’60, ’64, and ’68 are crossed out; apparently 1972 was on the horizon when the billboard was last revised). In a small, five-storey building, one window wide, could be found the Idee [sic] Amin Charm School. The big event of the era is hinted at by graffiti drawn by one of us on the side of R. Weardly’s drugstore: “UP WITH NIXON.” U.S. President Richard Nixon’s troubles dominated public discourse in the early seventies, and my cousins the Sawyers, from Washington, D.C., were naturally well-versed. On our imaginary city’s storefronts and signs, up popped takeoffs on the names of prominent Watergate characters—then household words in the U.S., now nearly forgotten—most notably the storefront of Rebozo the Clown Amusements, a reference to Watergate figure Charles “Bebe” Rebozo, a friend of Nixon’s who accepted, on the president’s behalf, a hundred-thousand-dollar campaign contribution from the millionaire Howard Hughes. Innocent we might have been, but we weren’t naïve.

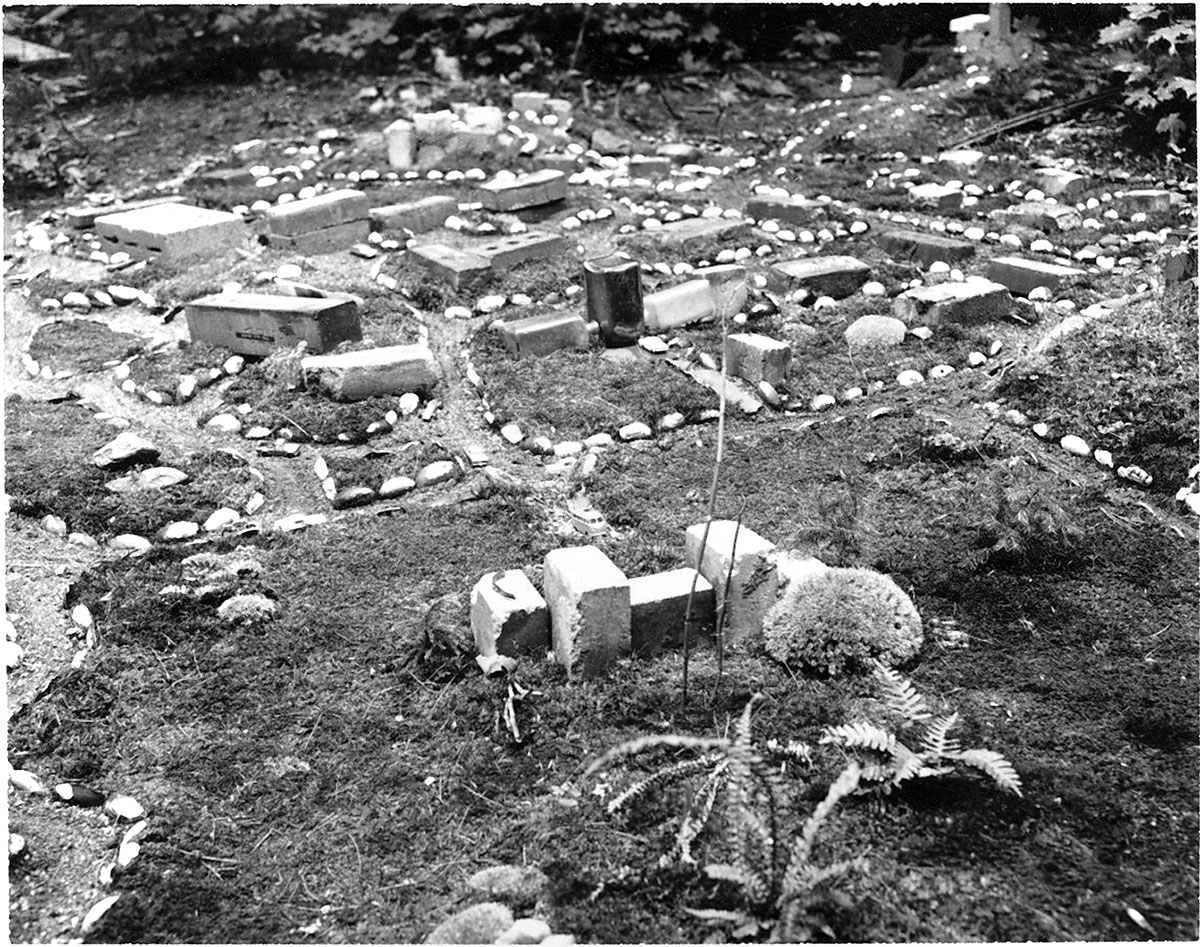

Boston, with its moss lawns, brick houses, and ferns, 1969.

We called our city Beaver, which sounds more virtuous than those shady characters inhabiting it, or their strange enterprises, or all the architecture of paper, ink, and Scotch tape seems to justify. The name was strictly a practical matter, the brand stamped on yellow fireplace bricks that were lying around, but knowing that tells us the city’s origins.

The story begins nearly a century ago, in 1914, when a plumbing contractor, Harry Wheelock, built an Adirondack-style summer camp (the term “cottage” is not used in the region) in the dark, lovely woods of Coates Island, just six miles from the house at 189 North Avenue. My mother’s parents bought the camp in 1946, and ever since it’s been a family gathering place in the summer months. As a youngster and teenager I’d do what I could to extend my stay when my cousins came.

Many of us have long assumed Coates Island trees aren’t in a hurry—can’t be—because of the thin soil and clay on the rocky island. It was that very clay, combined with gravity, that caused the camp’s original limestone fireplace to sink and shift toward the lake until it had to be dismantled—a noisy, disruptive project, lasting most of the summer of 1964, and still remembered with regret. The brick replacement was a handyman’s special, lacking details such as the original’s masonry arch over the top, which let smoke out the sides but deflected dangerous sparks back down the chimney.

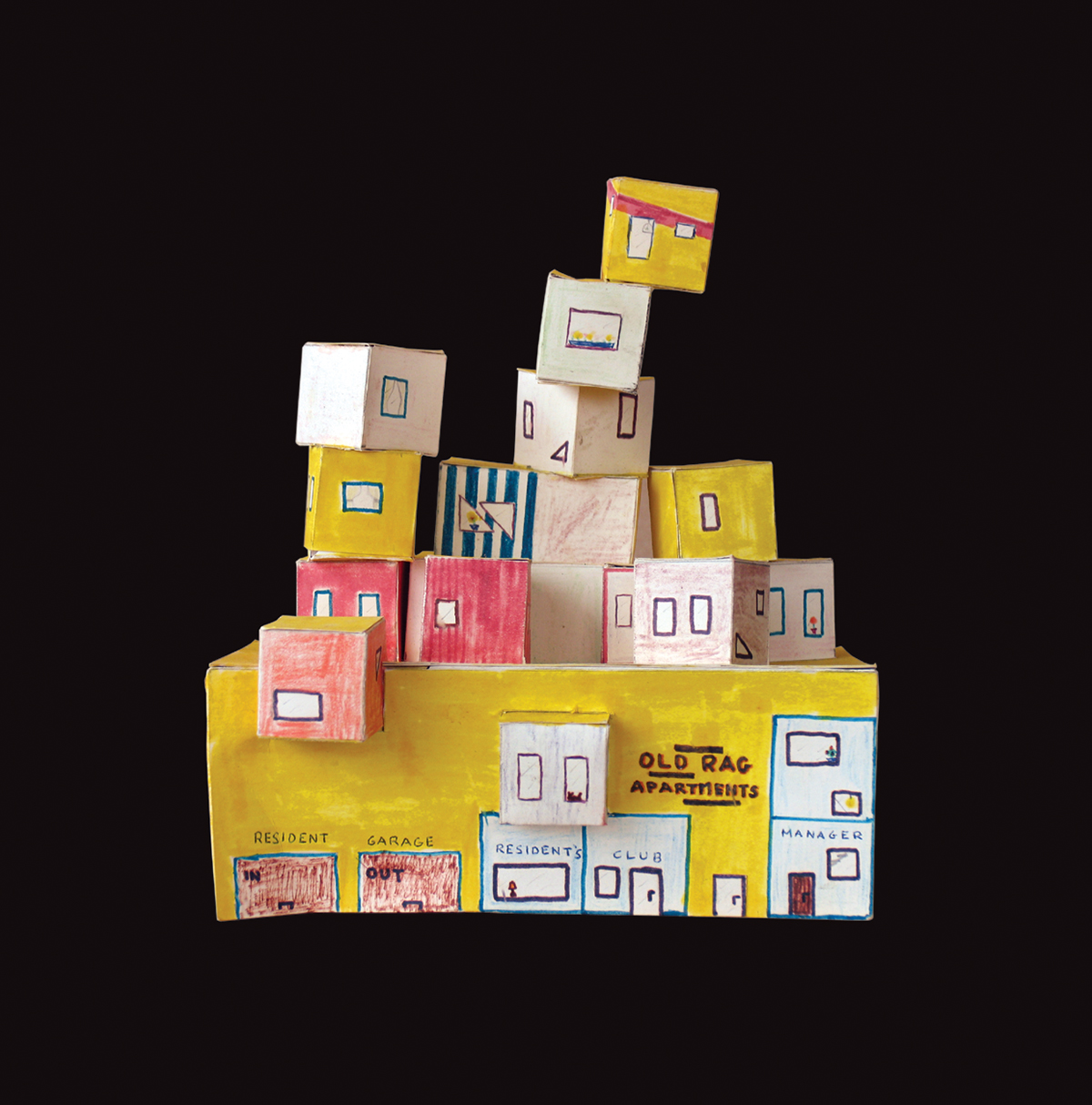

But cataclysmic events are not without their positive outcomes. The event released materials and energies throughout Camp Cedar Ledge that shaped us for decades. A pile of sand dumped near the garage, not used up in the making of mortar to lay bricks for the new fireplace, became a play area. We drove around in the sand with Dinky, Corgi, and Matchbox cars, and sometime in the summer of 1967, we began grouping bricks into a village we called Boston.

In succeeding summers, in the hands of young town planners, Boston grew rapidly along pastoral, suburban lines. “I think of it as having evolved from making mud pies with [my sister] Lynn up there,” my cousin Carol Sawyer remembers today. It was controversial from the start, due to the materials and methods used. “I remember it met with opposition from adults who wanted the parking space and objected to rocks in the woods being denuded of their moss to make our city’s front lawns,” says Carol. The bricks from the demolished fireplace, we decided, were convincing abstractions as buildings: hardy (they could be left out all winter) and versatile (they could be stacked and cantilevered like Expo 67’s Habitat).

We strip-mined the ancient rocks and sides of the cliffs of their moist moss coverings to use as lawn. As supplies ran low near the camp, we’d go on poaching expeditions far into the boulder-strewn woods. We also took rowboat trips to the other side of the island, to a cove near the camp of our other cousins (on our dad’s side), the Laidmans, where we would gather bucketfuls of freshwater clamshells washed up on a pebble beach. These black-and-white shells we used as curbing, to outline the streets. They achieved an original, pleasing, and urbane effect. We’d transplant hemlock seedlings and columbine flowers to gardeny Boston, both of which looked good on the landscape in combination with the geometric shapes of the bricks. We transplanted various other plants, from walking ferns to domes of an odd puffy moss that grew in circular mounds on dead wood. Since they weren’t far from home, most of the flora survived well enough. At season’s end, we’d lay plastic sheeting over the whole thing to minimize winter damage and keep leaves and needles off. A fringe benefit was that the clear cover created a terrarium effect, keeping Boston clean and moist and extending the season a bit. We assigned our aliases (I was Alfred Molden) nice lots, and put mansions on them. Lynn (Leitchen Treebird) had a thick piece of purple Vermont roofing slate to park her Matchbox Lincoln Continental on. Her estate was well-landscaped with ferns and rocks. My brother, Jeff (no alias), drew up a map, and from his numbered key I see that he, I, and the Sawyer cousins Carol (Carol Harbog), Brian (Nairb Reywas), and Lynn were all inhabitants. Two of the Laidman cousins, Stuart and Andrew, also took up residency.

By 1969, when I was eleven, with the cousins relatively close in age, there seemed no way to curb our desires to develop these Vermont woods. We began planning and building a whole region of satellite cities. Sprouting deeper and deeper into the forest were clusters of bricks from the expired fireplace, and now whatever else we could scrounge that made convincing buildings, including wooden blocks and glass booze bottles, mined under Uncle Alan Sawyer’s supervision, from an old dump on the property. There was Springfield, behind the garage. We located Mountainville high on the cliffs, as close to the edge as we dared—then and now a beautiful spot, where towering eastern white pines have engineered out competition by laying a luxurious pinky-brown mulch of dry pine needles that matt down so nothing else can grow. The cliff area was also cottage country for Boston, below. Each of us pretentiously developed, for our aliases, luxurious summer homes at choice rock outcroppings.

All over the place appeared villages whose names, such as Carol’s Cave and Jeff’s Rock, mirrored long-standing territorial claims among us. The names of Septic City, Leeching Fields, and Flushing Meadows reflected the 1970 installation of the camp’s new septic tank. Next to an oak rose the town of Rudson, the name a play on “sudson,” the suds being the real-life intermittent rivers created when anyone washing dishes in the camp kitchen finished up and dumped the plastic tubs of grey water outside (supposedly to “save” the septic tank). Rudson was never more than a hamlet, actually, but the name was attached to one of the power families of the state, the aforementioned Rudsons.

Further west of the camp, into forbidding woods, and past what we called the Poison Ivy Preserve, appeared the villages of Treton, Lone Swine, Birch Heights, and, finally, the Brasilia of the empire, Hillton.

The first Hillton was too daring, laid out Boston-like with bricks as buildings, amid sharp protruding rocks on a steep, eroding slope. On Jeff’s trail maps of the island, he called this area Dead Tree Ridge. The forest canopy above was so thick the lower branches of the ancient cedars there were starved for light and died off, creating a dimly lit wood of craggy, twisted dead branches. In 1971, we moved Hillton to a more gently sloping spot where a big rock jutted out toward the lake (though Old Hillton remained marked on my cousin Brian’s map). Like Brasilia, Hillton suffered from its remoteness. A colour slide I took with my Kodak Instamatic around 1972 shows nothing of the park-like grooming of Boston. At Hillton, leaves and forest litter falling from above triumphed constantly.

These towns all had to be connected, of course, by road and by air. The latter was easy. We cut out plywood planks in the shape of runways, coated them with polyurethane, and laid them on a flat spot with the usual strategically arranged bricks for airport terminals. The fleet was my own collection of Revell, Hawk, and Airfix plastic models—classics of period air travel, including Lockheed Electras, Vickers Viscounts and Vanguards, Convair 880s and 990s, and various Boeing and Douglas jets. One year, I built a cardboard model of Washington’s Dulles airport—Eero Saarinen’s masterpiece, with the roof that dips in the middle—and then waterproofed it with a coating of LePage BondFast glue (which wasn’t waterproof, and that forest insects ate).

As in real life, road building proved a more taxing undertaking. Surviving maps show dotted lines proposing an ambitious network of four-lane highways linking the three states of Cliffton (Boston, Mountainville), Trefernia (Hillton), and, eventually, Middiland (Beaver) as roughly a triangle.

Unlike the urban visionary Robert Moses, we were not always able to finish what we started, but much did get built. The need for bridges and maintenance challenged our resources and ingenuity, but produced constructs that were worthy feats. The rule was that surfaces had to be passable by Matchbox; realism and a consistent, convincing look were the requirements. The basic engineering was to strip away surface leaves and needles, down to the soil, surface the roads with sifted sand from the sand pile (a dwindling resource, eventually; the rougher sand sifted out was used for “dirt” roads). We’d line the roads with twigs, filling some gaps with gravel or soil, and bridging others with boards cut to fit.

When fresh, they looked good. But driving them by the rules (no flying cars) proved tiring, and nature responded to our intrusion with endless rain, wind, and leaves, and the push of nearby ferns and other plants to take back their territory.

But the busiest corridor got its superhighway: the B–BE, for Boston–Beaver Expressway. It led from the sand pile next to the garage, down the hill, somehow (curves and switchbacks, maybe tunnels) across a stone stairway—built over a period of years by Uncle Alan, from dismantled fireplace boulders—past the giant red oak next to the back door, down the east side of the camp, and into the cellar through a slatted door.

Like Boston, Beaver began as bricks, but its location opened other possibilities. Lake Champlain summer camps were usually built on posts, with dirt underneath enclosed only by lattice or wood slats. Because the land slopes down, a large area under the camp’s big front porch is useful for storing small boats, motors, life jackets, fishing rods, and other dock gear.

As very young children, we played in the dirt under the camp, around the stumps of trees cut down when it was built. It had become dry and granular, turning to clay when wet. We could see that the thin layer of rich, dark soil we found in our road building in the forest had a not-too-fertile foundation.

At one end of the area under the camp a long, narrow table with checkerboard designs applied as decals had been left. We painted a network of streets over it, and placed yellow Beaver bricks from the fireplace demolition as buildings. But what worked outdoors wasn’t as satisfying here. Since 1967, when Boston began, when I was nine years old, our skills and ambitions had grown, and sometime in 1970, the first cardboard building was placed.

Browsing the boxes in the attic at 189 North Avenue, in 2005, I saw that building—an elongated colonial-style structure, white with black shutters, and rather elegant. I recalled that it was positioned diagonally at the northwest corner of the table and declared to be the parliament building. This structure, like most of the early ones, was made from scrap cardboard obtained by my father, Clem, from his office at the National Parks Service of Canada, in Ottawa. He was involved in a government grants program advertised on one side of this cardboard.

“BOURSES D’ETUDES” and “SCHOLARSHIPS” you will read inside the Spongy Worm Apartments, and many other Beaver buildings. (Coincidently, the cardboard also carried the National Parks logo: the seal of a beaver sitting on his stick home.) The other side of the big sheets was blank, and made excellent construction paper; it was deliciously white and inviting to marker-pen ink, watercolour paints, and crayons. The paper was frequent cargo in our long trips by Volkswagen from Ottawa to Vermont.

One dry run for Beaver was a crude city built by Jeff and me in the attic of our home on Renfrew Avenue, in Ottawa’s Glebe area, starting in the fall of 1967. We put the bourses d’etudes cardboard to extensive use building freeways and factories. Toilet-paper and wrapping-paper rolls served as smokestacks. This was the Cleveland of model cities—immense and chaotic, filling the whole attic.

On the Sawyer side, “I think the closest precedent for Beaver from our family was large structures of wood blocks we would make in the basement, in D.C.,” my cousin Carol relates. “Cityscapes built to scale for Matchbox cars, including elevated freeways and office towers. We also had a few stray Lincoln Logs.”

When the Ottawa attic was finished, in 1969, the industrial city had to go, and a new, finer, more detailed one was constructed by me with my school chum David Stanley, who lived a dozen or so houses east. Slides I took of this city show large cardboard skyscrapers, their proportions reflecting the full dimensions of the sheets of bourses d’etudes paper they were made from. Visible in some images are a sprinkling of smaller cardboard structures, but our Lego bricks, Kenner sets, Anchor Blocks, and Tri-ang train sets provided most of the architecture and infrastructure. A structure made from a lesser-known set, Super City, is also visible.

My parents have home movies from the mid-nineteen-sixties showing that my brother and I were building cities even earlier, when we still lived in the Montreal suburb of Pointe-Claire. One brief clip in a now-fading eight-millimetre reel, marked “A Day With the Holdens,” shows me and my brother scampering around an impressive set-up combining Tri-ang electric trains and the Aurora road-race set that Uncle Buz gave us, probably for Christmas, 1963. Everything seems to be working at once, which, as I recall, was a feat.

The problem with the projects involving building sets was there were never enough parts. The lid of a box of Anchor Blocks emphasizes our frustration. It shows a boy and a girl at a table, having completed, apparently from the blocks in that set, an impressive complex with twin towers. The backdrop is a great urban skyline, slightly abstracted. Their approving father, in pinstripe pants and neat blue-and-black tie, is seated near the model, inspecting it. Flanking the image are smaller drawings, including two monumental bridges, also apparently made from Anchor Blocks. But we knew from experience you couldn’t build any of those things with the contents of our box.

The lobbying for Lego, through 1966, arose from the same defect. From the jaws of victory that Christmas came the discovery, later, that there were barely enough parts to build the town shown on the cover, notwithstanding the beaming boy and a girl, updated versions of the Anchor Block kids. We weren’t obsessed about the parts shortage, which was a common reality, but the seeds of discontent were there, and they grew, almost literally, in the bricks, moss and ferns that became Boston, in the shift in the attic in Ottawa. The drive was to cardboard, and the road to Beaver.

Surprisingly, Beaver did not die as we grew older with each passing summer, but grew more sophisticated and absurd. It reached a pinnacle in 1976, when I was eighteen. Over time, the buildings grew ever taller, stranger, and better, increasingly becoming a shell for the characters we created to live in them. “The real root cause of Beaver,” Carol told me in 2005, “is a love of storytelling and narrative. All the absurd names of businesses, the characters. The pleasure in cooking up further absurdities.” Carol calls the camp project a “fictional city,” which suggests something more than models, that incorporates the importance of the character, whose existence was supported by increasingly elaborate fictional events. Brian would comb through magazines and find pictures of faces that, uncannily, seemed to match the mind’s-eye appearance of particular characters. A biography card shows Grace L. Ferguson, the airline magnate, for instance, as a well-coiffed senior dame, wearing sunglasses, looking over cards picturing buildings, presumably real estate. “Age: in excess of 80. Style: very clever, volatile. Hobbies: deep-sea fishing. Residence: Broken Arms, Beaver.”

One of Brian’s inventions were elections, carried over, Carol thinks, from earlier races between stuffed animals at their house in Washington. In Vermont, we’d run them by cutting up hundreds of tiny pieces of paper, on which we’d written vote increments, an equal total for each candidate. We’d then draw them for a specified period of time. At some point the polls would close, and we’d count the ballots, and have a winner or a runoff. I see by the records for the 1974 national elections that J. Milford Squigley beat Count Igor Vicoius and Treetop Wunderunder for the governorship of Trefernia. Petunia Gumbody took Middiland in a race against Athram Nosdur, J. Herbert Praetell, and Jeremiah Codfish. Beaver elected Kenneth Cinycle, forty-nine, mayor. Platform: “anti-everything.”

“It only seemed natural to cook up our own elaborate plots or drawings,” Carol says. But, she thinks, “another factor in Beaver being created is probably the fact that Brian doesn’t like to swim. Think what there is for kids to do at camp: swim, go out in one of the boats, swim… play records on the Victrola, walk in the woods, swim, play cards, help the adults (pretty low on the list), go into town. Subtract the ones that aren’t fun to do when it’s rainy, and voila—a paper city is born, a participatory art/sport that many can play all day, an ongoing comic narrative.”

One of Brian’s inventions was a game called “fraughpp”—the national sport. No one knew how it was played, only that large sticks were involved. Brian managed to clip from magazines lots of photos of people holding sticks, from boaters wearing life jackets to seniors holding canes, and use them to put together the Fraughpp News, the sport’s official organ. Beaver’s team was the Pollutocrats (coach, Bealls Mutterly). Leading goalies at the time included Cashewbutter and LeToad. Sponsors who advertised inside the stadium Brian built for Beaver included the Lumpy Bread Company, Nosdie (the Nosdur’s run at competing with Diemart), and Ned’s Barnacle Removal (another member of the Erp group).

The Fraughpp News reported that one elderly player, the Awksford Goobers’ Voxsmith “Ace” Durk, “had a big night scoring 108 points as Awksford downed the Sprigfield [sic] TRILLIUMS 67–44¼.”

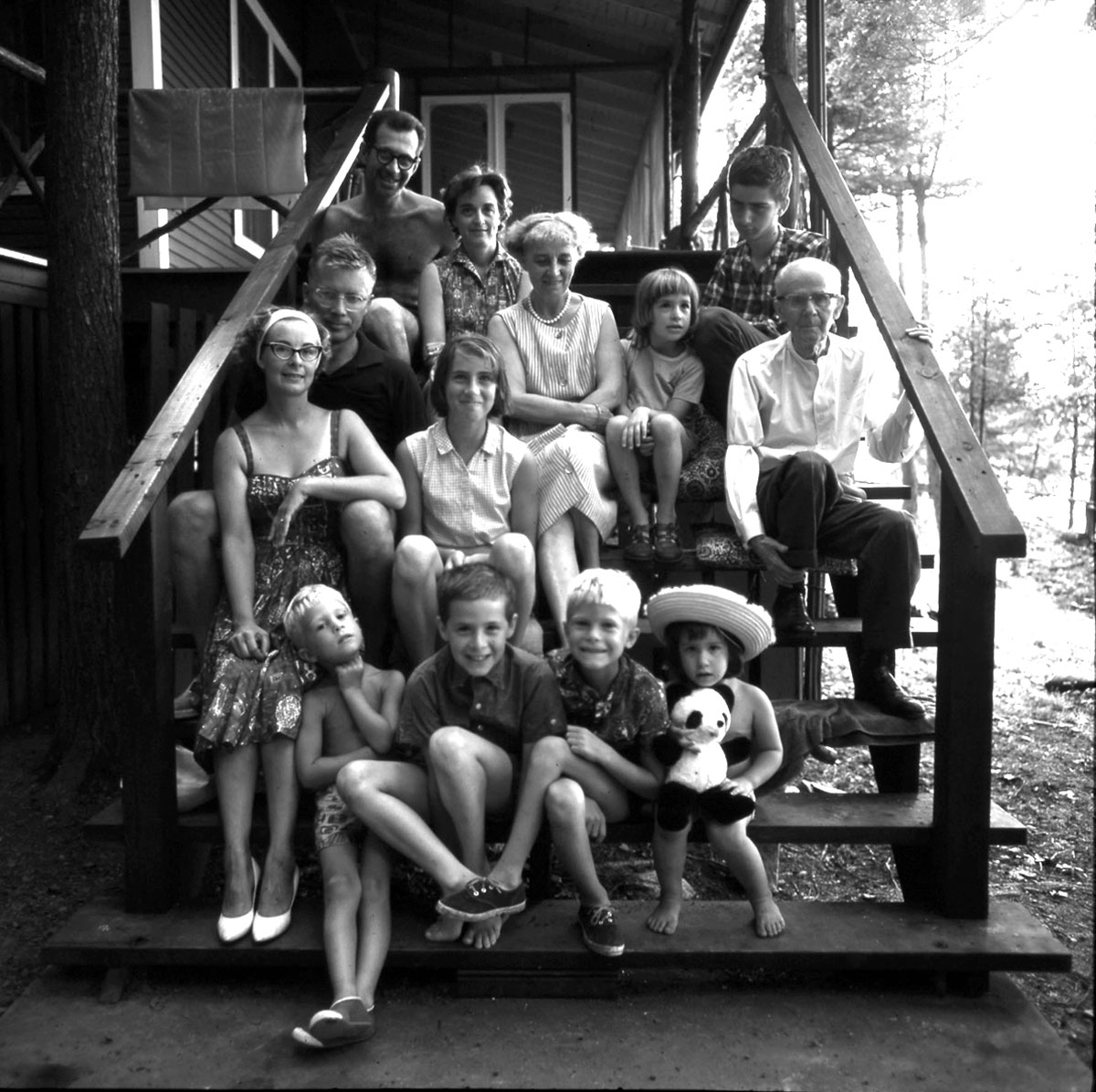

The author and his extended family, at Camp Cedar Ledge, circa 1963. Back row: Alan Sawyer, Erika Sawyer, Dana Sawyer; second row: Clem Holden, Erna Heininger, Lynn Sawyer, Alfred Heininger; third row: Sylvia Holden, Diane Sawyer; front row: Alfred Holden, Brian Sawyer, Jeff Holden, Carol Sawyer.

The building process was a rite of summer with its tensions and fallout. Alan Sawyer once famously said that humidity at the camp was so high you could “untie a pretzel.” It also buckled cardboard and led to mould. Add to that the fact the camp’s wood-slat skirt offered no protection from wind, which blew buildings over, and rain, which destroyed them, and it is clear both Beaver’s creation and survival were miracles. We dealt with the problems creatively, with partial success. Scrounging around the camp we discovered an ancient piece of canvas that had been cut to hang inside the screened-in front porch, a kind of storm curtain that we appropriated and hung just inside the slats. But the heavy, opaque fabric stole our light, so we switched to plastic, stapling the translucent sheets to the wooden slats. As young sailors, we should have been more aware of the power of the wind, which quickly tore the plastic away, and we took to nailing boards to the inside of the slats, spreading the load away from the staples.

None of these solutions truly worked, and Beaver regularly got blown away and rained on, something the boxed collection testifies to today, in running ink, leaning towers, and warped walls. Still, Beaver grew. When the long game table was filled, we made new real estate from gypsum board found in the garage. Sporadic urban renewal displaced some buildings; others were rebuilt. But there was nothing planned about it—our buildings grew taller and our city spread out, presenting visitors under the camp with quite the skyline.

Design and construction took place either on an old oak table in the relatively comfortable living room, or in an area of the front porch without screens, where we set up a long folding table from town. As the creations got bigger, the term “project building” came into use, shorthand for skyscrapers, sports stadia, factories, and other complexes that took days to draw and assemble. Tensions ebbed and flowed, among siblings and cousins. “I think I resented how much time making Beaver took away from Brian playing with me,” Carol says. She still managed to create such tidy jobs as the Porter’s Slum Visitors Center (dated August 8, 1974, with bars on the windows and a second-floor back door that opened into thin air), Porter’s Slum being the original table on which Beaver was built.

Though we’d broken free of the constraints of toy building sets, materials were never as plentiful as we’d have liked. Besides improvising with cracker and booze boxes, and the then-new Pringles canisters, we went on expeditions to Ben Franklin, a five-and-dime in the North Avenue Shopping Center, to purchase Bristol board (twenty-five cents a sheet, as a price tag inside a completed building attests). We also used up old campaign signs from municipal elections in Ottawa. Ed Henry, Tom McDougall, Joe Cassey, where are you today? Your campaign signs helped build quite another municipality than the one you wanted to serve.

Carol remembers “a lot of riffing on ideas, and cackling laughter” in the building of Beaver. It was, my older cousin Diane Sawyer remembers, an infectious project. “Eventually, it captured everyone’s imagination, so that sooner or later the older kids and even some of the adults got pulled into the project,” she says. Her future husband, Gerry Yuskauskus, built Gerry’s Roofing Company, among others, and Uncle Alan carved a statue of the municipal hero Tweedledorf L. Schneidelfinck, which we placed in a square (the only thing resembling a park Beaver had). “I remember,” Diane recalls, “one night at the round table [in the living room], all of us bent over our plans, the yellow light from the paper shades on the chandelier, the skinny markers that were always running out of ink. I loved the feeling of working separately, but together.” She compares it to SimCity, the computer game where players build a virtual town, complete with inhabitants and infrastructure. “I recently read an article in a teen magazine called JVibe. It was written by a seventeen-year-old about his childhood fascination with… SimCity. As the creator of these worlds, with the power to assign body types and attributes—even happy or sad interactions—he felt that he was playing at being God.”

A set of Anchor Blocks, such as we played with at 189 North Avenue, is pictured in the first catalogue for a series of building-toy exhibits the Canadian Centre for Architecture, in Montreal, has been staging since 1990. In the text opposite, the architect and author Witold Rybczynski describes construction toys as “a magical journey to another world.” He, too, sees a godlike aspect, where for young people, miniaturization “reverses the usual order of things.” They are given “an opportunity to control and dominate their surroundings.”

Other toys our extended family knew as kids are sprinkled through the centre’s catalogues, including Lincoln Logs, Erector sets (a U.S. version of British Meccano, handed down from Uncle Buz’s childhood), the plasticky Design-a-House that Buz, who was an industrial designer, gave us, and Kenner Girder and Panel building sets. The exhibit catalogues also include German toy villages similar to one that Helene Neumann, the sister of my grandmother, who remained in Germany, played with in her own childhood in the early twentieth century. She noticed my enthusiasm when I played with it on a visit with my mother in 1971, and gave the toys to me.

As we shaped these building toys, how did they shape us? Rybczynski suggests the obvious: “We know that architectural toys influence certain children in their later choice of vocation.” If he is thinking about architects, the epitome is the greatest of all, Frank Lloyd Wright, whose geometric designs reflect the toys he had in kindergarten. They were no mean toys, actually, but famous ones created in the nineteenth century by kindergarten’s pioneer, the German educator Friedrich Froebel. Kindergarten was one of the era’s phenomena, an educational innovation. Froebel’s twenty “gifts” were an important part of the program, a sequence of educational toys that included building blocks, weaving papers, sewing kits, modeling clay, and other building projects.

Norman Brosterman, an architect who collected many of the construction toys acquired by the Canadian Centre for Architecture, knew of Froebel’s creations and makes the case in his book Inventing Kindergarten that a whole spectrum of great art and achievement of the twentieth century was unleashed by kindergarten and Froebel’s constructive gifts to the children of the nineteenth. Wright was one in a million—actually, “one of millions of people, including most of the so-called ‘form givers’ of the modern era, who were indoctrinated, in effect programmed, by the spiritual geometry of the early kindergarten,” Brosterman writes. He plausibly calls the innovation “the seed pearl of the modern era.”

Such was Froebel’s influence that it was still detectable in Beaver, through such modernist buildings as J. Milford Squigley’s Le Corbusier–style headquarters. Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, who adopted the name Le Corbusier, was another notable who had absorbed Froebel’s kindergarten geometry as it conquered Europe’s education system.

Past and future both seem visible in Beaver’s cubist Ricardo de Hoya Candy Company, with its jutting, irregular walls and angles that, in the summer of 1976, uncannily anticipated the post-modern expressionism of Frank Gehry.

Froebel might not have anticipated, but surely would have approved of, the breakaway from the building sets Beaver represented. Interestingly, Inventing Kindergarten notes, discussing the prescribed uses of the gifts in kindergarten classes, “solid forms made good, albeit symbolic, models of objects… a stack of cubes a bed, and the more prismatic building blocks an entire miniature town.”

Beaver was not the work of kindergarten students, but by 1976, virtual adults. It was a detailed city, detailed in its architecture, filled out with people, politics, and a satirized (not sanitized) modern economy. It was not unlike Dominion, the model city created by the Canadian cartoonist Seth as on offshoot of “Clyde Fans,” a serialized story from his comic book, Palookaville.

Seth’s buildings, displayed at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2005, contrast with Beaver’s in their greater realism and a sophisticated greyness, though they seem every bit as improvised from nothing as Beaver’s, made from cardboard and paint. Dominion grew, Seth told Comic Art magazine, in 2004, as part of his planning for “Clyde Fans.” But, like Beaver, “it got a bit out of hand and became a project in itself.”

None of Beaver’s creators, in real life, became architects, though they largely followed the careers of their Beaver aliases. The lawyer Nairb Reywas (Brian) is a lawyer, practising in Manchester Center, Vermont. The artist Carol Harbog (Carol) is an artist, living in Vancouver. Leitchen Treebird (Lynn) became an Annapolis, Maryland–based language specialist—close enough to her artsy alias in brick-and-shell Boston. My brother Jeff (no alias), who charted the territory in the woods, today maps forests for a paper company in Federal Way, Washington. My alias, that Alfred Molden, was a lawyer. In real life I became a journalist—though one who often writes about cities, real and imagined.

Viewed from the twenty-first century, the buildings and people of nineteen-seventies Beaver appear neither real nor virtual, but occupy a vivid space in between. Says my cousin Diane, an erstwhile Beaver conspirator, a fan, and now a graphic artist based in Boston (the real Boston): “I think that Beaver represents the best of what was good about our childhoods—the time and space to dream up the ridiculous and the marvellous, and the time to play, to build, or make those ideas real.”