It was probably no more shocking to fans of the sport then than it is today, yet, on November 27, 1934, the Toronto Daily Star saw fit to run the headline “WRESTLING STAGE-MANAGED, OFFICIAL SAYS,” in screaming capital letters, from one side of its front page to the other. The sporting world’s worst-kept secret was leaked during a bribery scandal, when the local wrestling promoter Jack Corcoran, owner of the Queensbury Athletic Club, was accused of knowing the outcomes of his matches before the first head was locked. Corcoran’s reputation survived the scandal (he denied wrestling was anything but legitimate), and fans chose to continue to turn a blind eye—or simply not care—that their favourite pastime was more an entertainment than a sport.

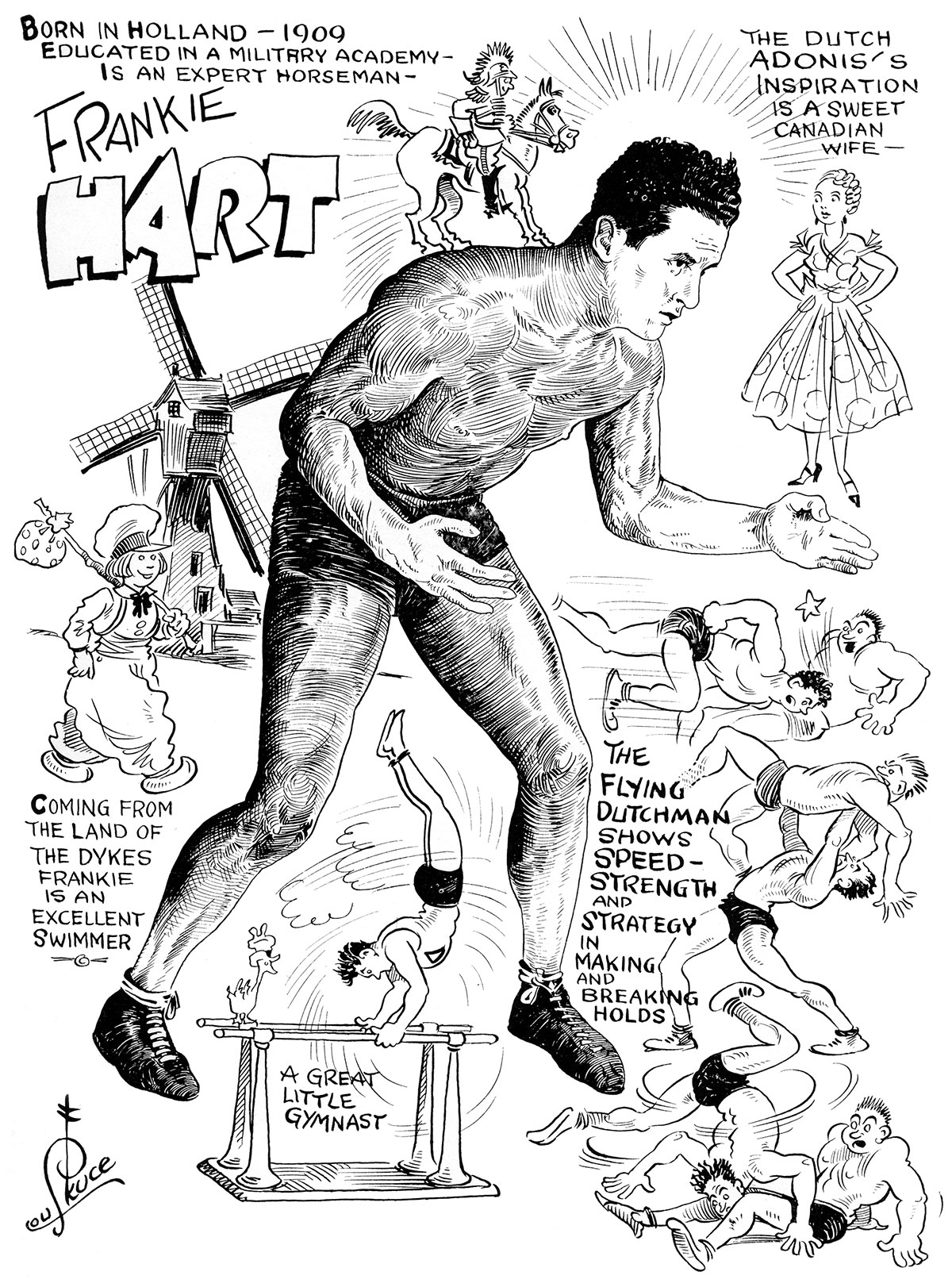

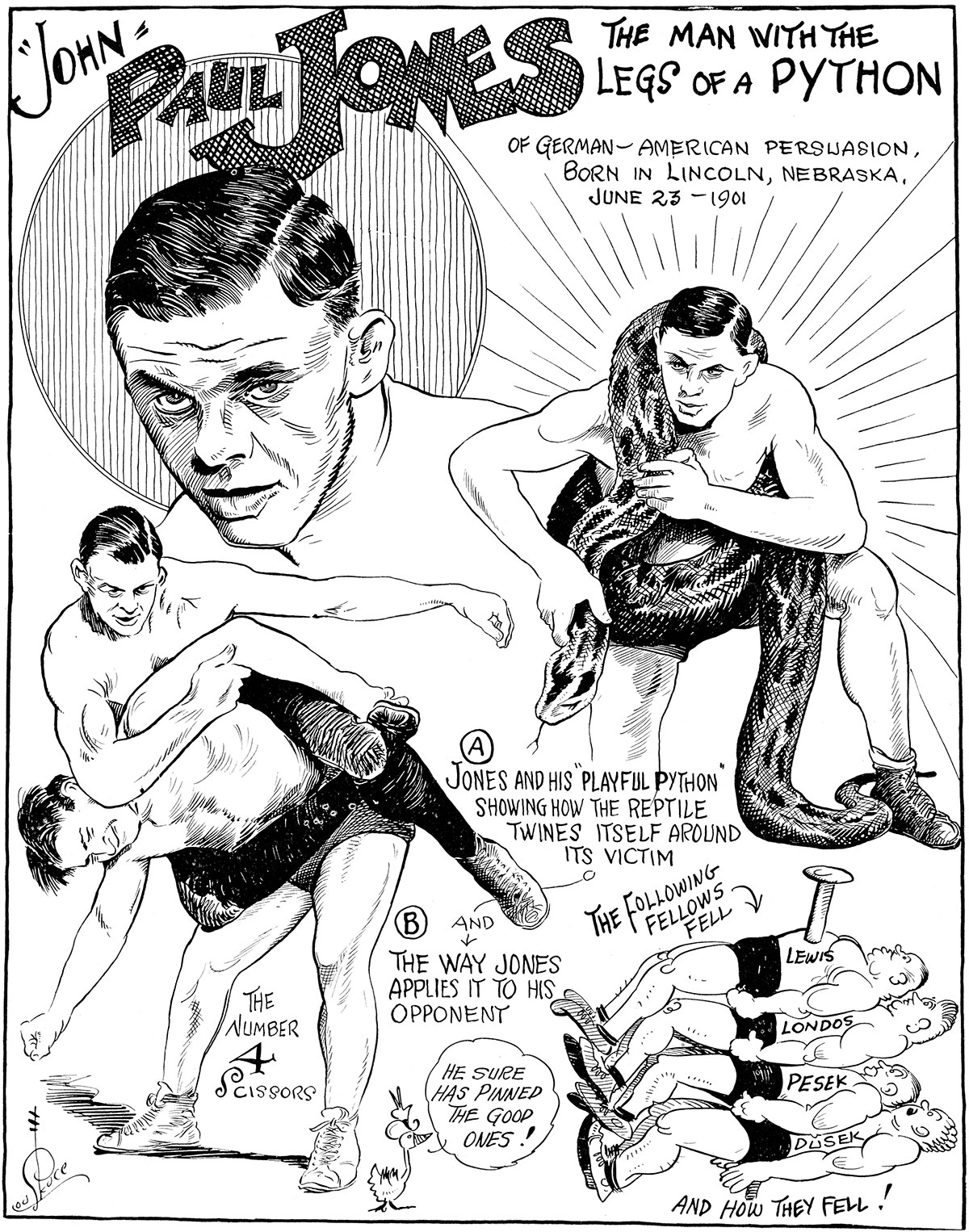

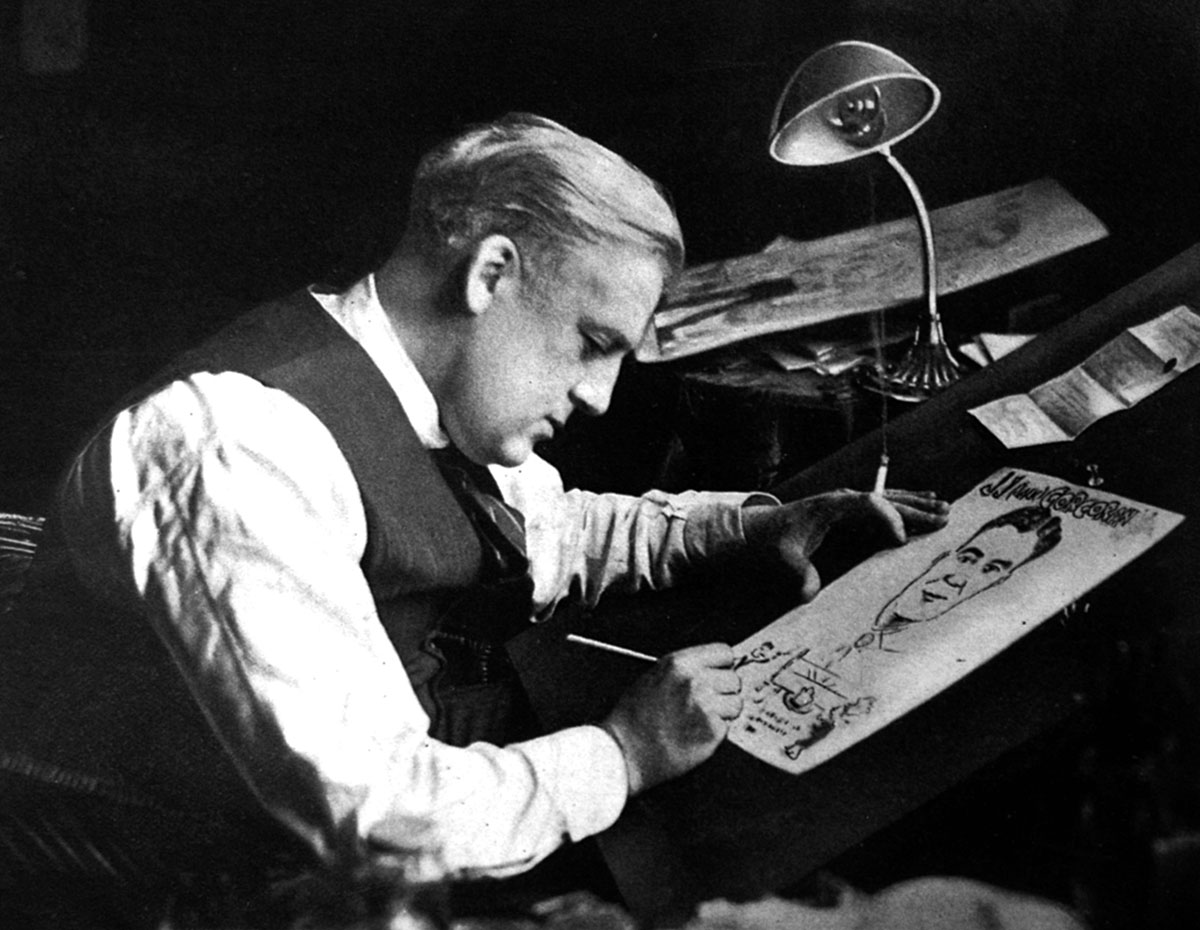

In 1935, Corcoran published Corcoran’s Wrestling Guide, a program featuring illustrated biographies of some of the day’s wrestling talent, drawn by Lou Skuce. A strip and editorial cartoonist, Skuce became something of an international celebrity throughout the thirties and forties, achieving a level of fame unthinkable for a newspaper illustrator today. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a strip artist like Gary Larson, or even a graphic novelist like Art Spiegelman, appearing, as Skuce did, in advertisements for the contemporary equivalent of Buckingham cigarettes or Plymouth automobiles. In the early thirties, the Tamblyn chain of drugstores even offered a free Lou Skuce comic scribbler with every twenty-three-cent purchase of Minty’s toothpaste.

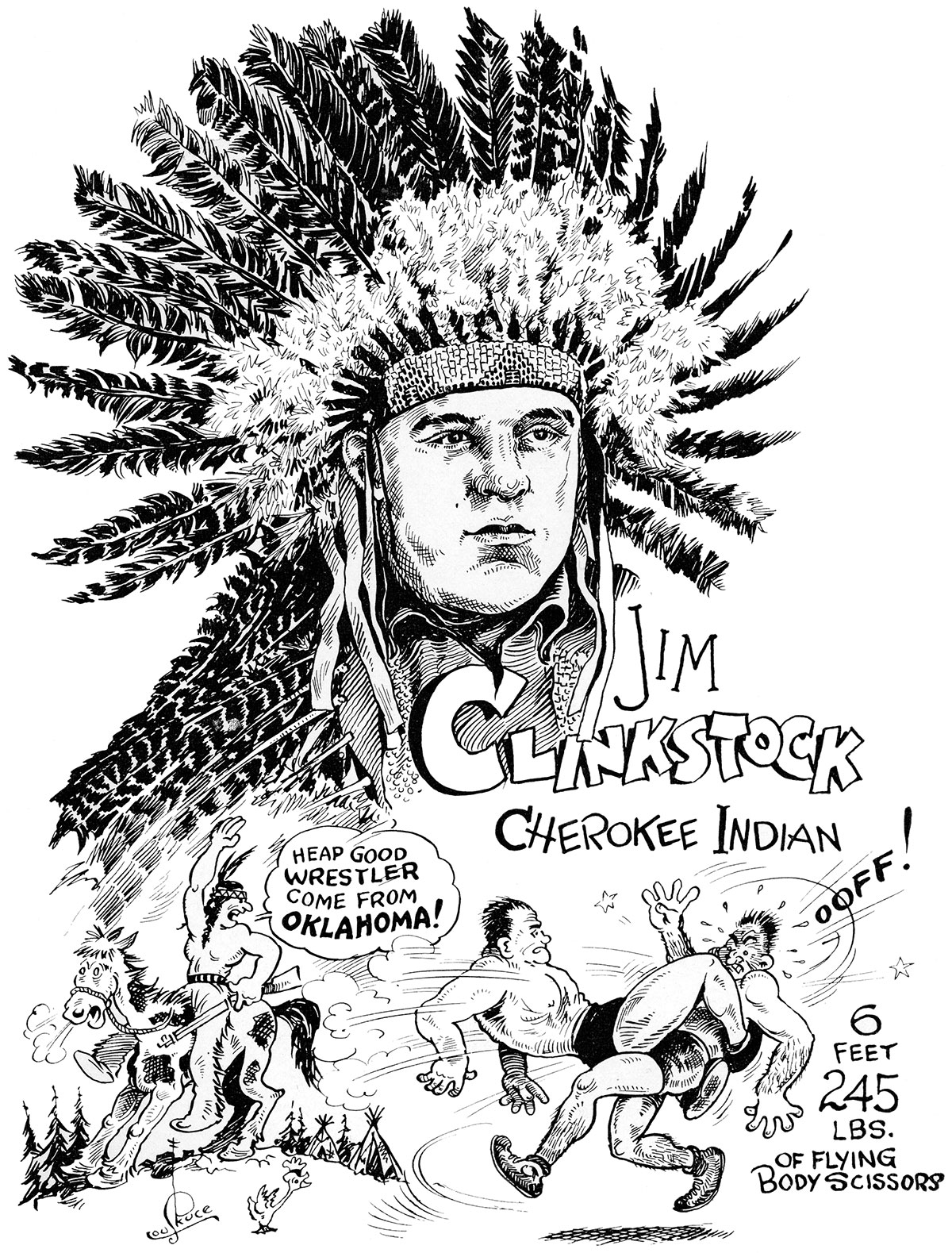

Corcoran’s guide showcased Skuce’s talents as a fine illustrator, top-notch cartoonist, and talented letterer all at once. Skuce, who specialized in sports cartooning, drew every wrestler with an elegance and grace that made each one look like a champion—even cultural stereotypes like Matros Kirilenko, “the Terrible Cossack,” with his ushanka fur hat; and Jim Clinkstock, shown in full Cherokee headdress.

Although forgotten today, by 1951, the year he died, Skuce was being billed as “Canada’s greatest cartoonist.” Perhaps fittingly, given his association with professional wrestling, he was remembered at the time not just as a cartoonist, but also as an entertainer, having made frequent public appearances, often at children’s shows, with his Cartoonograph, a projector that enlarged his drawing board onto a screen for audiences to watch him draw in real time—lest there be any cries of stage-managing.