A mild, bright afternoon in a dripping town weary of winter, traffic hissing along the slushy streets. Waites, in black jeans, a denim shirt, and snowmobile boots, sat at the counter over the Toronto Sun, two copies of the application form beside him. Aaron finally remembered him from years ago, when he and his friends visited the Donut Cove to use the pinball machines at the back. Waites had always been nice to kids, and a soft touch for cigarettes.

—Why don’t you fill this in, and then we’ll get some lunch? Waites said, without looking up. —You’re not working today, are you?

—No, I’m off, Aaron said.

Hoping lunch wouldn’t cost more than the four dollars in his wallet, he borrowed a pen from the waitress. He had tiny, precise handwriting, from writing in his journal, but for this application he printed in slow, block capitals.

Waites read the application over when Aaron was finished.

—Look’s good, he said.

Aaron got excited then; when he’d tried to apply at Allied Plastics, last fall, he’d been told they weren’t accepting any applications.

Outside, Aaron looked for Waites’s brown Caprice in the parking lot until Waites unlocked the passenger door of a black Chevy van.

—My new girlfriend, he said. The lenses of his glasses were darkening in the daylight. —Picked her up this week.

The van’s interior smelled of pine air freshener and cigarette smoke, and a black curtain hung behind the two bucket seats, blocking off the cargo area.

—I’ve got to make a quick stop before we eat, Waites said.

They drove around the park downtown, then north along Pulcher Avenue in a sudden, sun-drenched shower of big snowflakes. Waites steered with the wrist of his right hand, while his left hand held a cigarette aloft. If Waites could run two cars on what he made at Allied Plastics, Aaron would go along for the ride. A job there was his ticket out of the boarding house, extra money for his sisters, and eventually a car of his own.

—I told my mother about you, Waites said. —She said she knew your mom, used to see her up at the Red & White and Woolworth. We’re sorry about your loss, Aaron.

—Well, that was a while ago, Aaron said. —I miss her, but not as much as my sisters do.

—That’s what a life of hard work does, tires you out. Then you get sick and you haven’t got the strength to fight it off.

They pulled into a plaza where Pulcher Avenue became Highway 11, on the northern edge of town. Though the recession had emptied many units, there was still a lumberyard in operation, a Christian bookstore, a hair salon, and Spectacular Sounds, a small audio equipment dealership. Waites pulled a Blaupunkt car stereo from behind the black curtain.

—This ought to buy us a nice lunch, he said.

Inside the store, a big Technics system was blasting the song he was hearing everywhere, the one about standing in the dark by the band with the blond hair. Aaron recognized the owner as the fat man in the Hawaiian shirts who would d.j. all the high-school dances. Brian, the guy’s name was. As they approached the counter, Waites took him sharply by the arm.

—Why don’t you check out the merchandise? Waites suggested, as he released Aaron toward a display of portable stereos.

Smarting from the rebuke, Aaron fingered tape decks and tuners, some with the new digital displays, that were five times what he paid in rent. Soon he’d replace the turntable he’d inherited from his mother. If he didn’t screw up again. He should have known the transaction being conducted in murmurs at the counter was likely illegal.

Then they were outside again, Aaron blinking in the sudden brightness while Waites stuffed a roll of bills into his pocket.

—That fat idiot thinks he can screw me for a good radio, Waites said. —He’ll get his like the rest of them.

In a convenience store further along the plaza, Waites bought two packages of Player’s Filtered from an Asian woman and quickly unwrapped one to get a cigarette into his mouth.

—Goddamned immigrants are taking over everything, he said.

—So I hear, Aaron said. He hadn’t heard anything like that, and knew he’d have to overlook much more before he got the job.

—White people don’t work as hard as they used to, Waites said. —That’s why we need immigrants, ’cause they’ll work the hours we won’t anymore. Then we complain that there’s not enough jobs. I say people should stay in their own country and sort their problems out there, rather than bring them here.

—I heard English is the most difficult language to learn, Aaron said. —It must be even tougher trying to learn it while you’re working.

—That’s if they’re working at all. Lots of people come here looking for a handout.

They drove north again. On both sides of the highway bare patches of dark earth, dampened by the recent snowfall, showed in the windswept centres of the fields. This was the direction in which Aaron’s grandparents had lived. The countryside would soon turn marshy, the scrubby cedar and pine forests divided by the highway. He hadn’t been up this way since he was a kid.

At a crossroads named Reunion, Waites pulled into Galaxy Burgers, a flying-saucer-shaped drive-in restaurant. The silver-and-pink dining room was full of farming families at the end of their Saturday shopping expeditions. It smelled of vinegar and wet wool, the floor sloppy with muck. Aaron was relieved when Waites asked him what he wanted.

—Burger, I guess, Aaron said. —And a Coke. No, water. Water will do.

—You don’t want fries? Galaxy makes the best fries.

—I’m not that hungry, Aaron said.

—Sure you are. Have some fries. I’m gonna get some onion rings. You get some fries.

—O.K. I’ll get some fries.

Waites bolted his hamburger and onion rings, his chin shiny with grease, then started in on Aaron’s untouched mound of French fries.

—You ever fire a gun? he said.

—A bunch of times, Aaron said. —There’s a shooting range at the high school.

—Oh, I forgot about that. How about a handgun?

—No, sir, never.

—How come you didn’t stay on to finish Grade 13? You’re smart enough.

—Things were still kind of screwed up for me last year. I wasn’t ready for it. I’m going to college, though, when I get some money saved up. That’s why I really need this job.

—Leaving school will be the best thing you ever did. All it does is brainwash you into thinking you’re supposed to be poor. Doesn’t matter how hard you work. My father worked his ass off for years, and all it got him was dead.

Waites leaned closer to Aaron over the crumpled food wrappers and dirty napkins.

—People are cattle, he continued, almost in a whisper. —Take a look around you. They go to church every Sunday, they never break any laws. They think they’re happy because they’ve got food on their plates and a roof over their heads. Our prime minister talks about a just society, but justice for him means keeping things creamy for his rich friends and to hell with poor people—they know their place.

—I never thought about it that way, Aaron said.

—You’re a little young yet. You have to be out in the world a while before you see what’s really going on. Everything I know I had to teach myself.

—Well, you’re doing pretty good.

—I’m still working the morning shift at Allied, aren’t I? It’s even worse in England. There they elected a woman who actually tells people they’re stupid and lazy, that it’s their own fault they haven’t got any jobs.

—Doesn’t seem like there’s much a guy like me can do, Aaron said. He picked at the wax on the side of his paper Coke cup.

—Sounds like you’re giving up already. Did you read Dune? All’s we need is a real leader like that. But I’m too old now, and too ugly for TV. You like sci-fi?

—Yeah, but I haven’t read Dune.

—I’ll loan you my copy.

They drove back south on Highway 11, Waites smoking in silence, before turning onto a narrow sideroad cut through the cedar swamp. Meltwater had sloshed onto the road, leaving icy patches. When they crested a hill above the swamp, Aaron began to find the surroundings familiar. A turn in the road as they climbed, the first farms overlooking the swamp; this was the way they had gone to his grandparents’.

—I think we’re near where my dad grew up, Aaron said.

His memories of the farm consisted of isolated sensations and textures: his grandmother’s fat fingers as he helped her shell peas, the warm eggs he collected with his aunt, or sips from his grandfather’s bottle of beer as he sat beneath the lawn chairs. He had no memory of his sisters there, but sensed his mother’s presence in the way he could still feel the cool grass of the lawn against his leg. His sisters probably hadn’t been born yet.

—Tough farming in these parts, Waites said. —Did you want to stop in and say hello?

—I don’t know who lives there now, Aaron said. He mostly remembered his grandfather from the Castlereagh Oaks nursing home. Where his grandmother had gone he couldn’t say.

—I had an uncle and an aunt. That’s it ahead, I think.

Waites slowed as they approached a wooden farmhouse at the end of a tamarack-lined lane, its windows boarded up, the doors drifted in with snow, and the sun-blistered red paint showing many patches of wet, grey wood. The barn behind the house had collapsed, leaving jutting beams and mounds of blackened, rotten hay.

—For rent, Waites said. —Farmers are the poorest of the fucking poor. Anyone thinks he works hard should be a farmer for a week. Say, you’re not part of the Stanhope clan, are you? They’re from these parts.

—Who are they? Aaron asked. He had never known his mother’s parents, and had always assumed his mother was from town.

—Screwed up family, every one of them. Always getting into fights. Then one day, the son goes nuts, shoots his father and mother, chases after his sisters with an axe. When the cops came, he climbed a tree and shot himself. I was just a kid when it happened, but I remember playing Stanhope at school, climbing the tree and everything.

—I don’t think so. I’d remember hearing about that.

—You sure? Waites asked. He was smirking at Aaron, his eyes unreadable behind the brown lenses of his glasses.

—Come on. I’m just fuckin’ with you. The van moved faster on the better road above the swamp. Stands of pine and birch trees were reclaiming fields left fallow for too long. There were few farms in this area, and Aaron hadn’t seen another car since they’d left the highway.

Waites was smoking again, which Aaron had determined meant they were nearing their destination. They turned onto a rutted lane through the pine woods, at the end of which was a clearing with two great mounds of snow standing beside a massive hole. A gravel pit, he realized.

—This is a nine-millimetre Beretta, Waites said, as he pulled a black pistol from beneath his seat. —You are not really seeing this gun, because I do not have this gun. Understood?

—Yes, sir, Aaron said. —I got you.

—I got it in Michigan a few years ago. In the States, they understand that a man has a right to bear arms in his own defence. It’s right in their constitution. Our new constitution I wouldn’t use to wipe my ass. That goddamned Trudeau.

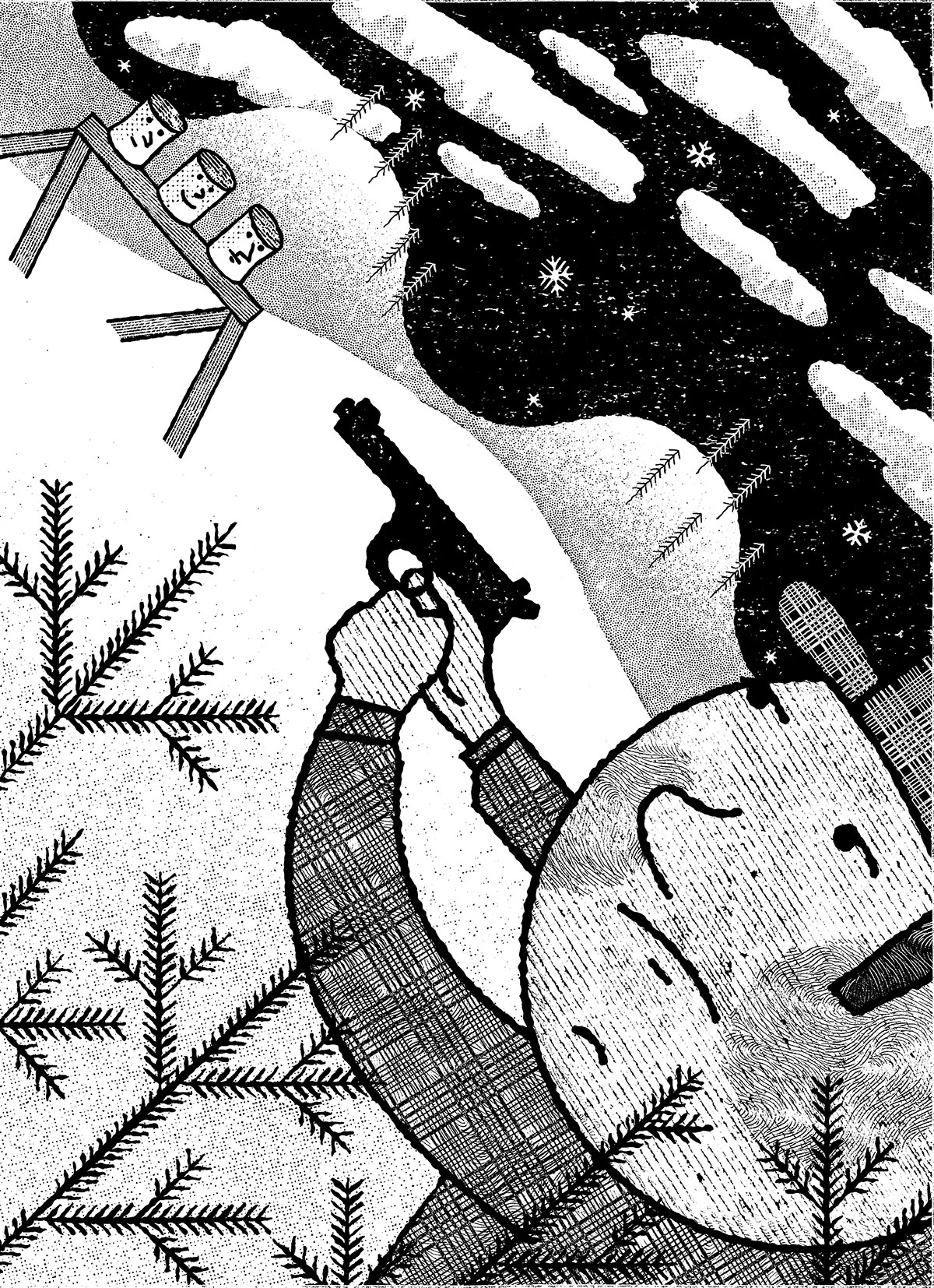

A chill had descended, winter reasserting itself after the warmer enthusiasm of midday. The wet snow creaked beneath their boots. Aaron followed Waites to the far end of the clearing, where they kicked snow off a wooden sawhorse. Then he helped dig through the snow for five rusted, bullet-holed tin cans.

—If a man’s to defend himself, he’s got to stay in practice, right? Waites said. —Here, take this. Get to know its weight. But be careful, it’s loaded.

The pistol was heavier than Aaron expected, and slightly oily. Waites pointed out the trigger and the safety as they walked back to the van. When he was finished, Aaron quickly handed it back. The gun scared him.

—Feet about a foot apart for better balance, Waites said. —You’ll be surprised by the kick this thing has. Arms like mine, right over the left. Watch now.

Waites fired off three rapid shots, wet firecracker pops that echoed off the mounds of gravel. One of the cans fell. Then he offered the gun butt-first to Aaron.

—How do I do this? Aaron asked. The gun was hot now, and the air stank of gunpowder. This was happening too fast.

—Stand like I did, Waites said. —Aim. Then think of those ass-wipes who wouldn’t give you a job.