Perusing the shelves of a used bookstore isn’t always about finding something you need. Many of us enjoy the thrill of finding something we don’t need or even didn’t know we needed. This could include a remaindered copy of a recent best-seller, an under-priced first edition, or a piece of local literary ephemera, like a chapbook, journal, or event program.

Unfortunately, the latter group is becoming especially hard to find, as independent booksellers trade their high-overhead–low-profit shops for virtual storefronts on the Web, or just get out of the business altogether. Big-box stores offer us books at sizable discounts, and Web sites like Amazon, AbeBooks, and eBay provide access to almost any edition of any title we might want. The way we shop for books has changed, and the discovery of an interesting item we weren’t looking for has become a casualty.

I first came across The Varsity Chapbook about eight years ago while flipping through the box of slim curiosities Janet Inksetter, the owner of Annex Books, used to keep on her counter, before moving her business on-line, in 2007. As a graduate of the University of Toronto and a former staff member of its Varsity student newspaper, the book caught my eye. It had a publication date of 1959, and contained thirty poems, some by names I recognized—Jay Macpherson, James Reaney, John Robert Colombo—and many more by writers I’d never heard of. I purchased the book for five dollars and went on my way.

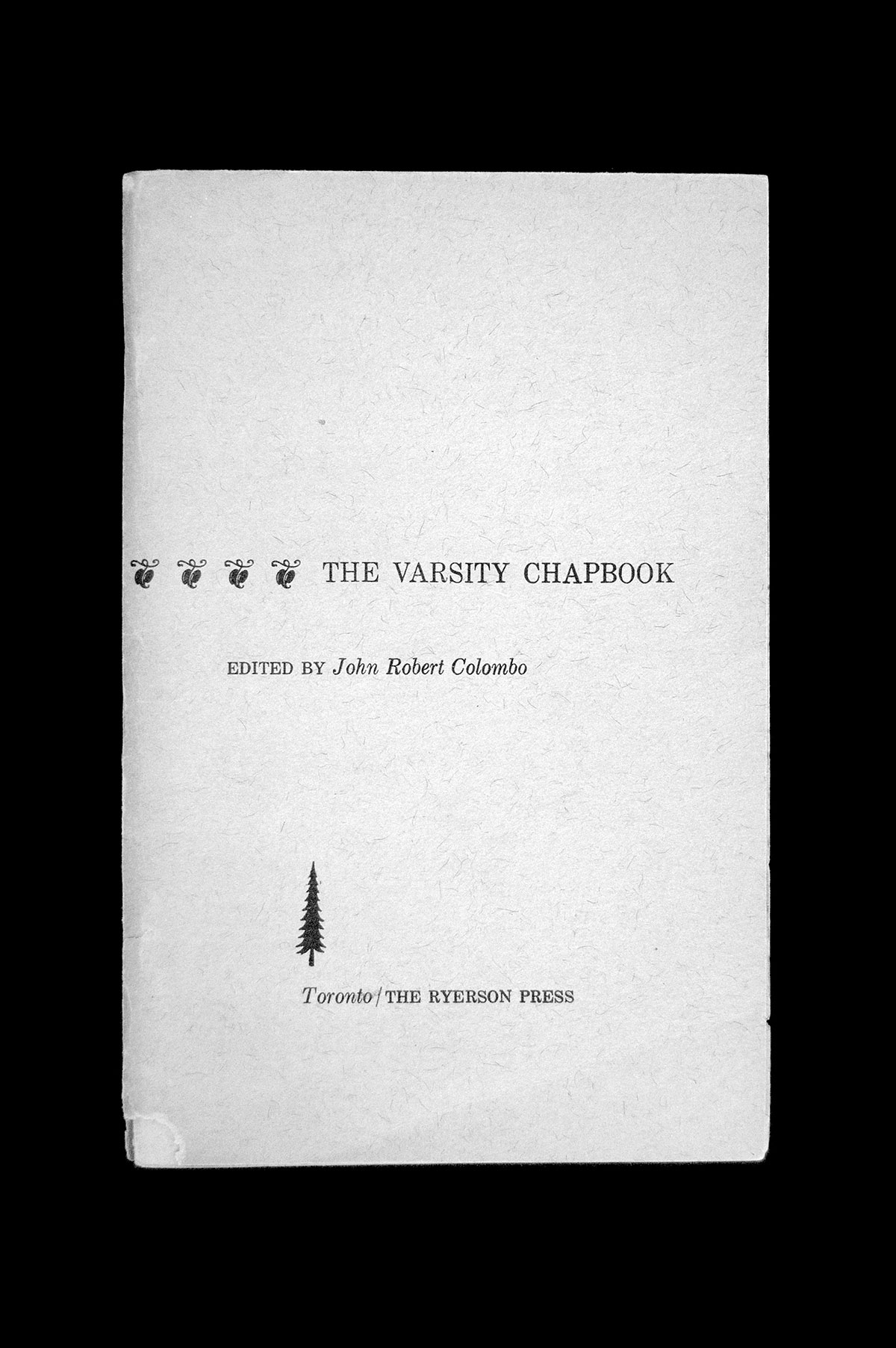

I occasionally still flip through The Varsity Chapbook. At five-by-seven-and-a-half inches, it’s much more handsome than the photocopied eight-and-a-half-by-eleven pieces of paper folded in two that are considered chapbooks today. (A chapbook is a small booklet of poetry or stories, usually self-published. Its name is taken from “chapmen,” the peddlers who initially sold them.) Its pages are book quality, and the card-stock cover has the added touch of a French fold (a sheet double the necessary size, folded twice at right angles to each other—sort of a double cover).

Finding such an interesting piece of Toronto history by chance once is rare, yet I have inexplicably come across copies of The Varsity Chapbook for sale twice more since my Annex Books find. Last year, I recognized the name of one of its contributors, Alexander Leggatt, on Taddle Creek’s subscriber list. I contacted him to see if he was the same Alexander Leggatt, and received the following note in return: “Yes, it’s me. Two things I’m curious about: why did you ask…and how on earth did you come by a copy of the Varsity Chapbook? ”

Toronto’s literary scene in 1959 wasn’t as robust as it is nearly a half-century later. Book launches were usually small, invitation-only affairs, and reading series were still such a novelty that they garnered attention in the daily news. Most of the activity was taking place on university campuses, and writers such as Margaret Atwood and Gwendolyn MacEwen were just starting to define what would become modern “CanLit.” Like almost everything at the time, the literature and poetry of Toronto were considered second-rate compared to that of Montreal.

One of the more sizable presses publishing poetry in Canada was the Ryerson Press. Founded in 1829 by the Methodist Church, the Ryerson Press had a history of publishing everything from denominational material to trade books to fiction. The press’s editor since 1922 had been Lorne Pierce, a Methodist minister. Pierce’s determination to restore Ryerson’s reputation as a major publisher of Canadian literature helped launch the careers of several noted Canadian authors and poets, including Frederick Philip Grove and Dorothy Livesay. In 1925, he launched a noted series of poetry chapbooks that, unfortunately, was often noted for its varying degree of quality. Pierce’s desire to develop a large Canadian list had its downside: Ryerson had to accept some manuscripts that weren’t very good.

John Robert Colombo was also publishing poetry in 1959, but on a smaller scale than Ryerson. His imprint, the Hawkshead Press, released broadsides and other small publications by Colombo and others. (In 1961, Hawkshead would publish Double Persephone, Atwood’s first collection of poetry.) Colombo transferred to the University of Toronto in 1956, after two years of undergraduate studies at Waterloo College (now Wilfrid Laurier University). By 1959, he was a student in the university’s School of Graduate Studies, and active in the student press, writing for various newspapers, and editing Jargon, U. of T.’s first campus-wide literary journal. Soon, he also began organizing events at the Bohemian Embassy, a loft on St. Nicholas Street operated by the writer Don Cullen, presenting readings, jazz, theatre, and comedy.

“John was an entrepreneur, to put it mildly,” says Leggatt, now sixty-seven and retired from a teaching career at U. of T.

“I’d heard a rumour that the Ryerson chapbooks were going to be discontinued. They’d run out of poets,” Colombo told me when I contacted him recently to put an end to my curiosity surrounding The Varsity Chapbook. “I wanted to meet Pierce, so I came in out of the blue and suggested not only a collection focusing on a group rather than a single poet—which was a departure that he hadn’t thought about—and second, that it survey the Toronto scene.”

Pierce was intrigued, but insisted Colombo wage a literary battle and couple his book (which would end up featuring work by U. of T. students and faculty) with another featuring poetry from McGill University in Montreal.

Colombo wasn’t keen on pitting the poetry merits of U. of T. and McGill against each other, still he agreed and set out to find an editor for the rival publication. Within weeks he met Leslie Kaye, a McGill arts graduate, at a literary event and recruited him for the job. The war was on.

The Ryerson poetry chapbooks were designed in-house and looked anything but modern in 1959. Covers often featured line drawings that would not have been out of place in the nineteen-twenties or earlier, and many of the books looked rigid and formulaic in design. Colombo wanted his chapbooks to have a more contemporary feel, and asked to bring in his own designer, Harold Kurschenska, a fellow Kitchener, Ontario, native who was working as a compositor for the University of Toronto Press and a few years earlier had founded a small imprint of his own, Purple Partridge.

“Harold had a great deal of taste—no training, no education, but loved type,” says Colombo.

The design of Kurschenska’s two identical chapbooks is quite plain (his work on Jargon the previous year is much flashier), and yet it is this simplicity that makes them elegant. Their covers, aside from title and editor’s name, contained nothing more than a line of fleurons and the Ryerson Press logo. The interior design was not radically different from the press’s previous chapbooks, yet the placement and choice of type brought the series years ahead from where it had been.

Ryerson chapbook Nos. 189 (Varsity) and 190 (McGill) were published in December, 1959, and sold for one dollar each. They were reviewed not only in the student press (the Varsity newspaper alone announced the release at least three times), but also in the dailies of both cities and in several national journals—something no chapbook publisher could hope for today. The reviewers took Pierce’s bait and chose sides—usually McGill’s.

“The Varsity Chapbook fails to fulfill the hope of its editor that it ‘will shatter, once and for all, the illusion that, of Canadian universities, only McGill is producing its quota of top-flight poets,’” read a review in Canadian Literature, quoting Colombo’s preface. Desmond Pacey, writing in the Canadian Forum, took a somewhat more creative stance, likening the battle to a hockey game, pointing out that, while Varsity consisted of work largely from students, Kaye had stacked McGill with more established poets, such as Leonard Cohen and Phyllis Webb. “It is hardly a fair contest,” he wrote. “It’s like putting a good professional team against a group of simon-pure amateurs bolstered by one or two old pros.”

Varsity and McGill were the last Ryerson chapbooks overseen by Lorne Pierce. He retired in 1960 and died the following year. Although his successor was encouraged to let the series end, it survived for a while longer, but soon folded. By 1970, the press was hemorrhaging money, and was sold to the Canadian arm of the U.S. publisher McGraw-Hill.

Colombo’s faith in Kurschenska, who died in 2003, was well-placed. The Toronto Star, in an otherwise underwhelming review, called Varsity and McGill “more pleasantly and gracefully designed than has generally been the case with Ryerson chapbooks.” Kurschenska had a distinguished career (he designed Marshall McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy, the book that popularized the concept of the global village), with most of his working years spent at the University of Toronto Press. This past March, the Communication Designers of Toronto named him one of “Toronto’s Design Pioneers.”

Now seventy-two, John Robert Colombo has long been regarded as Canada’s Man of Letters. His youthful entrepreneurship never faded, and he has published countless poetry collections, reference works, and anthologies—The Varsity Chapbook being the first.

“I was quite pleased that I had managed to do something in a traditional way that was contemporary in feel,” says Colombo. “That’s what I’ve been trying to do all my life. It was a step in my career—a very minor one. Is it a significant one? Not as far as the public’s concerned. But it is to me.”

Montreal’s literary scene wasn’t ready to capitulate to Toronto in 1959, but even then, Toronto was starting to produce a strong team of “old pros” that would rival, and arguably best, Montreal’s in the years to come. The Varsity Chapbook didn’t give McGill poets any reason to be worried, but it may have been the unheralded first shot in a larger battle.