Dale locked his car door and walked toward the parking meter with a handful of change. A note, written on a piece of lined yellow paper, was taped to the glass that protected the time-indicator arrow. Instead of the usual out-of-order explanation, the note read:

DEAR WENDY,

I know only you’ll understand. Please read them all.

Yours,

MARCUS

Dale looked back at his car, a blue Volvo with four doors, distinguished only by a small dent below the driver’s-side lock. His gaze returned to the note, then to the right.

The next meter also held a piece of yellow paper. A long glance showed that each grey, metal, coin-eating tree appeared to have similar specks of yellow.

To the left was the same. Across the street was also a flip-flap of yellow.

He wasn’t late or early. If he fed the meter now, he could shop for low-sodium cereal and tins of organic chickpeas at the health-food store one block north and still be on time for lunch with his sister, Rachel. Alternatively, once the money was in the meter, he could wander this block, study each of the notes, and forget about shopping.

Dale lifted the yellow note and slid a dollar into the slot. He turned the dial. One hour purchased. A quarter and a twist. Fifteen more minutes. Another quarter, and a final turn of the dial.

A parking meter was a vending machine in reverse, Dale thought, where coins didn’t buy a crappy toy in a bubble or a tiny handful of stale peanuts. Only time and the absence of a parking ticket.

He decided to walk to the meter to his right. If the note added anything to the first, he would keep going in that direction—the yellow tags, he assumed, were in sequence. If the note was confusing, he would retrace his steps and walk right.

The street was a short dead end, an overlooked place to park at the very rear corner of the city’s historical district. On one side was a tall wire fence, protecting a large field of yellow grass and rusty weeds—a prairie made toxic from decades of industry. Across from Dale’s car, on the other side of the street, were the backsides of several buildings: a restaurant, a ceramic store, a rug shop. It was a tame part of town, a compromise choice for meeting with Rachel.

His sister had no doubt used the pay garage two blocks over, Dale thought. He had saved himself at least four dollars by parking here.

At the next meter, the note read:

We loved love letters.

Dale lifted the note and studied its underside. Moving in the opposite direction, he walked past the first note, to the meter on the left.

The virtue of defects is oft overlooked.

Dale stopped and called his sister to say he was running late. She sighed into the tiny hole of her cellphone.

Near the dead end was a large oval lump meant to facilitate U-turns. There were another three parking meters with yellow notes on the left. The first read:

Anaphora. Let me say it again: anaphora.

Next:

Pen will kiss paper, again.

Finally:

First memories stolen from a hotel lobby.

The notes did not seem to be in any sequence. The first note, the one attached to his parking meter, was meant to be read first. But the rest were random offerings.

Across the street were nine meters. A red four-door occupied one spot near the dead end. A Yamaha motorcycle was in another spot, closer to the entrance of the street. There were no other cars or observers.

He crossed the street to read the other notes.

I still hear your footfalls echo inside dead malls.

Our happiness developed in the pauses between photo-booth flashes.

You stitched random moments together into an insecurity blanket.

Everyone but me thought it foolish to chase after a girl with a ten-speed.

These notes, unlike the notes on the opposite side of the street, seemed to build toward something. But then the next note read:

DEAR WENDY,

You’re in the middle of things. Be sure to read all my thoughts.

Yours,

MARCUS

Dale peered past the wire windows created by the fencing. A chipped slab of concrete lay even with the debris. He walked toward the final four notes on this side of the street.

Too much suction, not enough foresight.

The best answers blur like a Lomo photo.

You wanted cigarettes without the cancer.

I wanted affection without affectation.

He crossed the street to read the remaining three notes.

String and glue and I love you.

Two corrugated lives can never walk smooth.

Too much coffee. Not enough gin.

The circuit complete, Dale stood one parking space away from his car. After looking at his watch, he decided to put another quarter in the meter.

He jangled the remaining change in his pocket. He ignored the cellphone as it began to vibrate.

Then there was a glint. In the middle of the street was a quarter, a few metres away from his Volvo’s rear bumper. He walked over and pocketed it, listening to the tinny clatter as it joined some new friends.

He paused for a moment and looked down at the road. He put his right foot on the white line that bisected the asphalt and moved his left in front of it, as if he were walking a tightrope. Arms spread for balance.

Slowly he turned his head toward the backs of the buildings on the block, all antiqued red brick. Former factories. The three-storey building on the corner had large windows on the second and third levels, and a smattering of ivy creeping north. Offices. The ground floor had a double set of metal doors where restaurant staffers smoked cigarettes and tossed heavy garbage bags into a communal Dumpster located near the street’s rump.

One of the desks on the third-floor office faced the window. There was a man sitting at the desk. This man worked in a loft, and no doubt lived in one too. Dale immediately hated this loft man, and then hated himself for coveting such an obvious, airbrushed lifestyle—a guilty pleasure torn from an expensive, glossy magazine.

The third-floor-office man looked up from his silver laptop and saw a strange fellow standing on the white line. The office man stared, then stared some more. Dale moved his left arm toward the office man, at the same time lowering his right arm, like a child pretending to be an airplane. He waggled his hand.

As the office man gave a cautious wave in return, the first click occurred. Dale stopped waggling and stood straight again, rigid in his tightrope posture. A second click. A third.

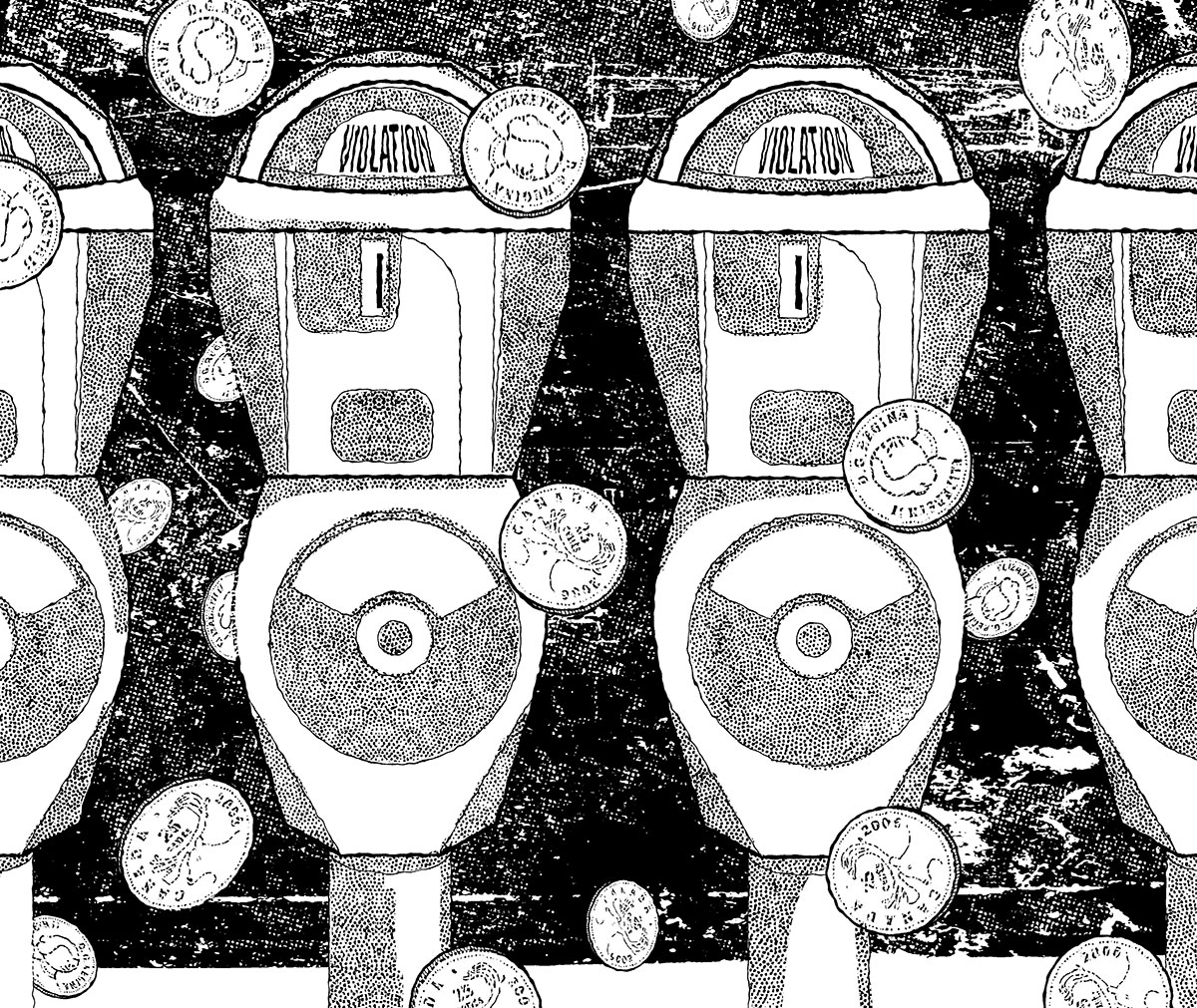

There were four parking meters in front of him, and four behind. To his left he heard another click, saw a flash of red. To his right, a “VIOLATION” sign appeared for a moment behind one of the yellow notes in a meter window.

Now there was a click from the opposite direction. The knobs of the meters were turning on their own, alternating from side to side. He watched them ping and pong until all eighteen had clicked and clacked on their own.

For a moment, enough time only to exhale, there was silence. Then the clicks resumed, and every knob turned, in perfect synchronization, to the right. Then the clicks leapt from side to side in a rapid staccato. The intensity of the clicking increased, and then increased again.

He waited, shoes on the white line, silent and motionless. His cellphone began to vibrate again. When it stopped, quarters dropped from the sky, a cloudless blue canopy. The percussive, shimmering rain of coins became the opening bars of Dale’s favourite new tune, a song like a jukebox being emptied of money.