Rebecca and Jack are on the chairlift early in the morning. Rebecca says her ankle still hurts from her fall the previous day. Jack looks off toward the horizon, balances his poles carefully, and taps the front of his skis. A tune. He taps out a tune that makes Rebecca sit up and listen and briefly stop complaining about her ankle, until eventually she says, “It won’t stop throbbing. Like there’s a miniature heart in my boot.”

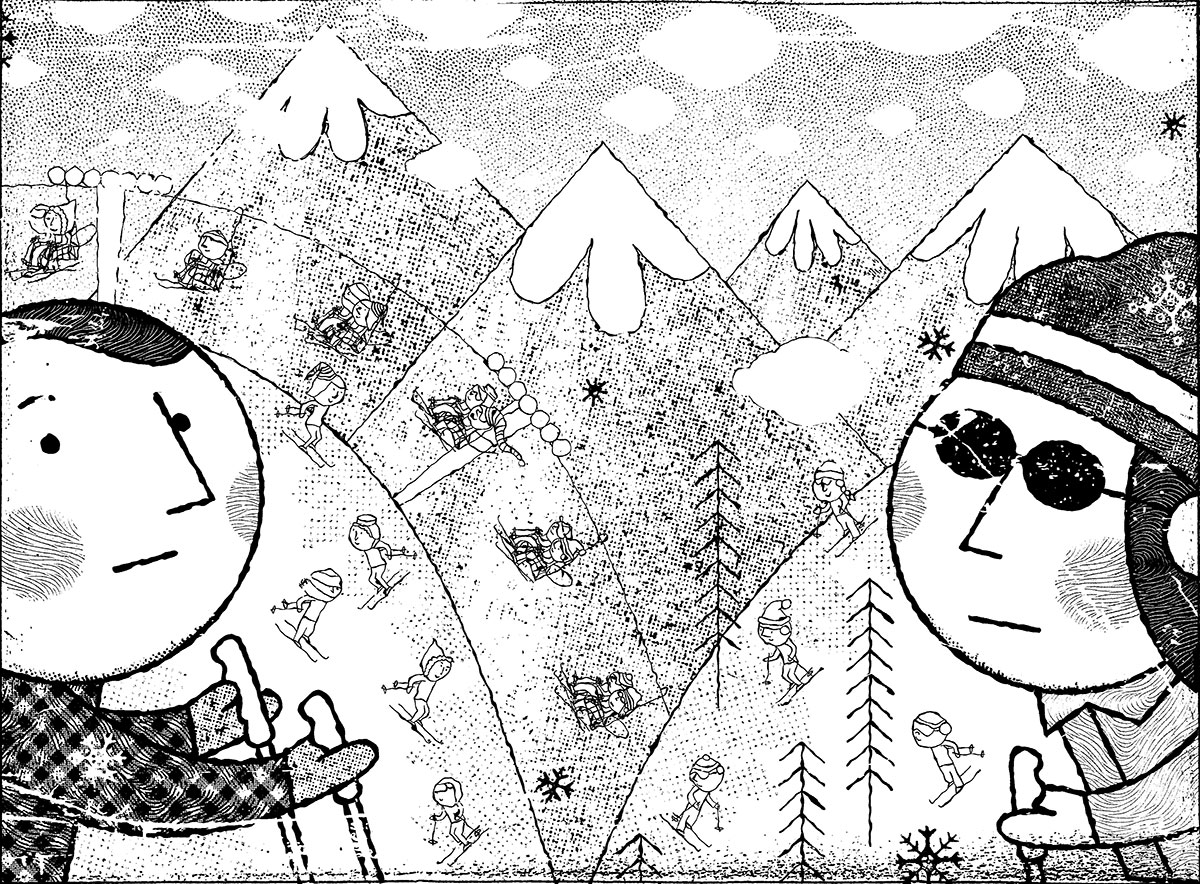

At the top of the lift, Jack wants to turn away from Rebecca, to ski off onto another hill, another chairlift, but this is their first vacation in ten years, their ten-year wedding anniversary vacation, and she wants to talk. And talk she does. That’s why Jack wants to be on another hill. What about the tune in his ski, the tapping tune? Or the bird calls? Or the calls of all the kids? Those will come later. They are not up and skiing yet. Too early. But soon. The calls of all the kids as they fall down the mountain. It amazes Jack that they do that. Fall. All the time. Up and down, up and down. Especially the snowboarders. Jack would like to snowboard, but Rebecca won’t let him. She says he’ll break his ankle and then, Jack thinks now, it’ll throb. Throb, throb, throb.

The hills are getting shorter, it seems. Two days into the vacation, and they’ve done all the hills, and now they know them and the hills feel short. The chairlift feels endless, slowly winding its way up the mountain, screeching and making towering noises that fill Jack’s head. But not enough to overpower Rebecca’s chatter. She reminds him of a bird, he thinks. He’s never thought that before. Ten years of marriage and suddenly his wife is a bird, a duck—something twittering and honking and…no, not a duck. More like a little bird. Because she’s small and lean and, well, her nose is a bit beaky.

Not fair, Jack thinks. This is not fair. He’s just not used to being with someone so much. He needs his alone time. That’s what Rebecca calls it. Alone time. Up time. Down time. Alone time. Ridiculous.

Down the hill and back on the lift. Again. Here they are again, seconds later it seems, and Rebecca is talking again. Her sentences stop at the top of the hill, halfway through, and then continue when they get on the lift. Right in the middle of a word even, she’ll keep that train of thought and go with it on the next lift up.

“It’s just a little throb, really,” she says. She turns her head and looks out from her ski goggles at Jack. He looks a bit yellow because her ski goggles are tinted, but he’s still handsome. She slides over toward him. Thinks about last night, about the fireplace in their bedroom and how Jack tried to light a fire and couldn’t, and how she finally took over and lit it, trying not to make him mad. She was, after all, a camp counsellor as a teenager. She spent every summer, all summer, making fires in the wind, with little or no firewood, for groups of shouting kids. But Jack got all huffy about it, and soon Rebecca was wishing she could douse the fire with water and go to bed.

Lovemaking last night, Rebecca thinks, wasn’t up to par. Distracted by the fire, Jack seemed distant. And Rebecca has been worried about her stomach lately—it’s getting pudgier than it used to be. The forty-year-old bulge. She kept trying to hold it in as Jack worked away above her. Grunting. And then she grunted, she knows she did. One big grunt. Because holding her stomach in while moving back and forth, well, it’s hard. But probably good for the muscles. Jack looked at her when she grunted. She could feel him looking, even with her eyes closed, and she wondered what he was thinking.

Rebecca takes Jack’s hand in hers. His mitt. She can’t feel his fingers through all the padding. There are probably only fifteen or twenty people on the lift. They have the lift to themselves. Rebecca talks about what they will have for lunch. And then where they should go for dinner. The hotel? Into town? Then she brings up the kids. She likes to talk about the kids. All the time. Jack stares off over the horizon. Perfect, Rebecca thinks, perfect to sit up high like this and talk about their two kids. At home with the grandparents.

Up at the top of the hill, Jack skis ahead quickly. Rebecca has to skate to keep up with him. Her ankle aches.

“Wait up. Where are we going? ”

Jack moves through a path in the trees. Effortlessly. Rebecca thinks he’s an effortless skier.

Jack thinks he almost wiped out there. One too many moguls too close together, and the trees are thick. The path through the woods is ungroomed.

They stop together at the top of a hill. One of the harder ones. Rebecca sighs loudly and says, “It’s beautiful today.”

Jack looks down toward the lodge, toward their hotel, and knows he should be feeling lucky. Not everyone can go skiing, he thinks. It’s expensive. It’s a rich-man’s sport. But then he thinks that he deserves it, this sport. Because he works hard. Not that everyone doesn’t work hard, that’s not what Jack is thinking. But that doesn’t mean he should deny himself some fun.

Although, lately, skiing hasn’t been so much fun. When he skis with the kids they just whine about the weather, about their socks, about the fit of their boots. They both want to snowboard, but Jack won’t let them. Not until they are old enough to drive themselves to the hospital with a broken neck, he says. Although he knows that makes no sense. Especially since he wants to try snowboarding himself.

There she goes. Rebecca swoops down the mountain. Good form, Jack thinks. Parallel skis. She bends nicely. She’s wearing a light pink snowsuit that looks great with her dark hair.

Yes, he should feel lucky. But he would rather be anywhere right now than here. He’d rather be at work. If he really thinks about it. Jack doesn’t know what is wrong with him. It’s the silence he’s missing. Or is it? Is that what it is? Quiet? At work there are noises, people all around him. Talking. Meetings. Maybe it’s the fire last night. The fact that he couldn’t make it flame brightly.

More likely it’s what Rebecca is saying. Nothing. She talks and says nothing. Jack would rather hear the kids on the hill screaming “fuck” when they fall.

Yesterday there was a girl on a snowboard. Maybe fifteen. Her blond hair braided, coming out of her helmet. Jack could tell she was pretty under her goggles and helmet. She came down the hill beside him, then in front of him, and then she fell. She leaned back when she should have leaned forward, and she toppled over in front of him. She called out “fuck” to her friends behind her. Jack passed by quickly, knowing she was O.K., and thought to himself that he’d never heard such a pretty word before. “Fuck.” It was full of laughter.

Rebecca is waiting for Jack at the bottom of the hill. She can see him, up top, right at the start of the hill. Just standing there. “What is he doing? ” she thinks. He has no helmet on, not even a hat, although it’s cold, and his hair is puffed a bit from the wind. She can see that from all the way down at the bottom. At least he still has hair, Rebecca thinks. She taps her poles on the ground, waiting. She looks around at the sudden influx of kids and parents and teens. Having slept in, everyone awoke to see the sun, and now the hills are full of people. Rebecca thinks of her mother with the kids, thinks of what her mother said to her about how only rich people can ski and how lucky they are to have been married ten years and be able to take ski vacations. Her mother, the social do-gooder. Volunteers at the Y.M.C.A., in the soup kitchen. Her mother wouldn’t ever click on ski boots and feel the wind as it hits her face going down the hill. What good is life, Rebecca thinks, if you spend the whole of it worrying about everyone else?

Rebecca knows that’s selfish, but there are times you just want to be selfish. You just want to do things for yourself, or for your family.

Here comes Jack now.

“What were you doing? ”

“Just waiting for those other skiers.”

Rebecca looks around. There are no other skiers.

“Thinking,” Jack shrugs. “We’re not racing, right? ”

“Right. Nothing is a race.” She laughs.

“You don’t have to be a bitch about it,” Jack says. He gets into the line at the chairlift. Rebecca holds back, astonished.

“Bitch? ” she thinks.

When she is sitting next to him, Rebecca taps his ski with her pole. She decides not to be angry. Just like that, Rebecca can now decide not to do something—get angry or sad or go to a party—and she won’t do it. That’s the beauty of age, she thinks. At some point you just say to yourself, enough is enough. No more people-pleasing.

Her mother, however. She can make Rebecca angry.

“I wonder how the kids are doing,” Rebecca says suddenly. The two teenagers next to them on the chairlift look over.

“Nice day,” Jack says. He nods.

Rebecca smiles.

A girl in grey and black, and a girl in a powder-blue suit. Lovely. Her hair and eyes are complemented by the blue. Her hair is braided and long. She has rosy cheeks. A snowboard. Maybe next year Rebecca will get a blue coat.

The girls just look at Rebecca and Jack. Jack knows it’s the girl who said “fuck” yesterday. He knows what they are thinking. That he’s old. That he’s there with his wife who is vomiting up stories about their kids. That he is trying to be young again. He knows they are thinking that when they are as old as he is, they won’t be skiing. They’ll be in an old-age home. That’s what he would have thought when he was their age.

The chairlift stops. Creaks to a halt. Swings.

“Fuck,” the girl in blue says.

“Yeah,” her friend says.

“Oh my,” says Rebecca. Like an old lady, Jack thinks. “Oh my.” When did she start saying that? She can build a fire. She can ski all day. Why is she saying “oh my”?

Jack looks down and sees a family of four skiing below them. The snow falls off his ski tip and lands quite near a little boy, who skis through it, oblivious. In fact, Jack thinks, he could probably spit and the boy would ski through it without knowing. Family of four. Perfect family. All skiing together. The father laughing proudly. The mother looking snug in her snow pants. Her ass bulging. At least Rebecca’s ass doesn’t bulge, Jack thinks.

Why doesn’t Jack talk to her, Rebecca thinks. Only in their room at night. Or in the restaurant after a glass or two of wine. But he doesn’t talk to her on the chairlift. It’s just occurred to Rebecca that maybe she and Jack are having problems. Not just little relationship spats, but real solid problems. Maybe not doing anything alone for so many years has really affected them. Maybe they don’t know how to be alone together anymore.

Their children are with her mother and father. Probably recycling and eating vegetarian and putting up protest posters and hanging out at the Salvation Army. “Ha,” Rebecca thinks. At least her mother and father have a good relationship. Solid. Her father talks to her mother, at least. They have something to talk about.

Rebecca wonders when Jack stopped talking. She can’t remember. And then she wonders when she started talking so much? It was with the kids. When the kids were born she couldn’t stop talking. Wanting more attention. Wanting more of Jack’s ear. His eyes and his mind were always occupied with the kids. Their freshness, newness, tininess. She wanted some of him.

At work, she doesn’t talk so much.

Rebecca turns to the girl in powder blue and says, “Do you mind not swinging the chair? It makes me nervous.”

The girl’s foot stops swinging in her snowboard. “Whatever,” she says. Surly.

Jack groans and looks away. The lift starts up again and rushes toward the top of the hill. Getting off, Rebecca is knocked slightly by the snowboarders. At first she doesn’t think they meant to do it. Snowboarders always seem awkward getting off the lift. But then, when they stop to put their feet in the board, strap themselves in, Rebecca can hear them laughing. Saying, “Good one.” Rebecca gathers herself and skis up to them.

And then she does something she never thought she was capable of. She pushes the girl in powder blue over. The girl is standing, waiting for her friend, both her feet in her board. Clipped in. She looks so perfect in her powder blue, her shining blond hair, her blue eyes and tinted cheeks. She has strong, long legs. Rebecca pushes her and the girl tips in slow motion, then goes down quickly. Like a domino, she knocks into her friend, who has just managed to stand up, and soon the two are splayed on the ground in the snow. Rebecca skis past quickly and down the hill. She loses Jack in her haste. In her escape.

Jack helps the girl up, lifts her under her arm and feels the small bulge of her breast with his fingers. He almost drops her he is so astonished and sickened by the placement of his fingers. As if they weren’t his own. But she doesn’t seem to notice, and she laughs as she bends now and helps her friend up.

“What a bitch,” the girls say. At once. And then they laugh. Jack laughs and says, “Yep.” As if he doesn’t even know her, even though the girls know she is his wife. They’d heard her talking on the lift about their kids. But everyone chooses to ignore this and they head down the hill together, and then up the lift together and down again. And Jack talks a bit. And laughs. And finds out the girls can say more than “fuck.” They talk about the terrain park, and which run is the best, and where the jumps should be instead of where they are now. And they talk about the pool at the hotel, and that there was a cute guy there last night who, the girl in blue says, is in love with the other girl. And they laugh some more.

Down the hill, up the next lift, down again, not thinking about anything but the feel of the hill under her skis. Rebecca spends a lot of time alone. When she sees Jack, out of the corner of her goggles, he is with the girl in powder blue. He is laughing and talking.

Jack has a good time and it isn’t until his stomach growls that he thinks of Rebecca and realizes, suddenly, that he hasn’t seen her for a long time. He looks at his watch. Almost dinnertime.

“Shit,” he says. And the girls laugh, because, as Jack realizes again, they think it’s funny someone his age knows how to swear.

Jack wonders how his daughter is doing. She is just six, and he wonders if she’s going to swear when she’s fifteen. Of course she is. And snowboard. And talk about guys in pools. He likes it most when she leans up next to him on the sofa, if they are watching TV together or reading, when she puts her soft head on his shoulder or his chest and she sighs deeply. Kind of like the sigh Rebecca made earlier on top of the hill. Big sigh. As if she is holding the weight of the world on her shoulders. It’s too heavy, and she has to lean her head on him for help.

Jack thinks there’s something deeper happening to him here. Deeper than a mid-life crisis, than young girls giggling in powder-blue snowsuits. Deeper than his wife’s incessant talking, than her fire-building abilities, than their wedding anniversary vacation alone. Jack realizes that this deepness has to do with his fear. He’s growing older, and the rest of the world is staying young. Or it seems that way to him. He’s growing older with his wife. And it’s almost as if he blames his wife for that. Rebecca feeds him, washes his clothes, makes the bed—can’t she control the aging too?

“This is ridiculous,” Jack thinks. And just then, as he’s swiping down the hill, making short cuts, digging in, Jack sees Rebecca ahead of him, racing toward the finish line. He speeds up, or tries to, but ends up with a face full of snow. He has to climb the mountain a bit to get his skis, which have popped off. The two girls pass him giggling.

“Fuck,” Jack says.

They laugh louder.

Jack finds Rebecca is nursing a beer, and her ankle, by the fire in the bar of the chalet. He sits beside her, picks up her leg, under the knee, and rubs her ankle. She tries to smile. His touch is rough and hard. But if she pulls away, she doesn’t know what will happen.

“Nice fire,” Jack says. “Did you make it? ”

Rebecca rolls her eyes.

All afternoon she skied alone. And quietly. She would let everyone go ahead of her on the lift so she could sit by herself. So she could look down on the skiers and up to the sky and over the top to the lake way down there, frozen over and so white it hurts to open her eyes fully to look at it. She would think about nothing. Talk about nothing. Say nothing to anyone. It was good, Rebecca thinks now. To have some peace and quiet. To not have to fill in the blank spots.

“I didn’t even know,” Rebecca says, finally, after Jack has got himself a beer at the bar and his cheeks become flushed by the fire. “I didn’t even know we were fighting.”

Jack looks at her. Looks at her small frame, her dark hair and eyes. Her hair is sticking up a bit in the front from her helmet. She is wearing long johns and a turtleneck. A fleece vest. They are sitting before a fire that Rebecca didn’t make. Their kids are at home. They are lucky, Jack thinks. And then he laughs.

“Neither did I,” he says. “I didn’t know we were fighting either.”

“It was a beautiful day, wasn’t it? ” Rebecca says. She yawns.

“Tomorrow is supposed to be nice, too. I asked the guy who runs the ski shop. Sunny. No wind.”

“Good,” Rebecca says. “No wind. I like no wind.”

“Dinner? ” Jack says, finishing his beer. He stands. He helps Rebecca stand.

“I might like to go back to the room first,” she says. “Fix this hair. Call the kids.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Jack says. “Your hair or the kids.”

He takes her hand and leads her into the restaurant. He leads her past the tables filled up with other skiers, with women and men and little kids and teenagers. There are some older couples there. Everyone seems to be smiling. Cheeks are flushed. Wine is being poured. The noise level increases gradually over the course of the evening.

In the dark, in their bed, Jack takes Rebecca in his arms. She grimaces when his leg knocks into her ankle. His elbow hits her hip. And then they fit like gloves. Tight together.

“I still don’t even know you,” Jack whispers, finally, just before Rebecca falls asleep. “I still don’t even know myself.”

“Maybe that’s O.K.,” Rebecca thinks. But she doesn’t say anything, because she’s asleep.