Douglas Coupland has been kicking around Toronto this month, promoting his latest art installation, Everywhere is Anywhere is Anything is Everything. Coupland and I talked a bit about his early career as a sculptor, when I interviewed him in 1995—a time when he hadn’t yet fully re-embraced his visual artistic tendencies. My piece is little more than a “Hey, remember the nineties!” lark. Much more interesting is the documentary Coupland was touring (along with his fourth book, Microserfs) at the time—Douglas Coupland: Close Personal Friend. I’ve linked to it in the interview. Watch it and, as you listen to Coupland’s societal theories, keep in mind that neither the Web nor mobile culture were things at the time.

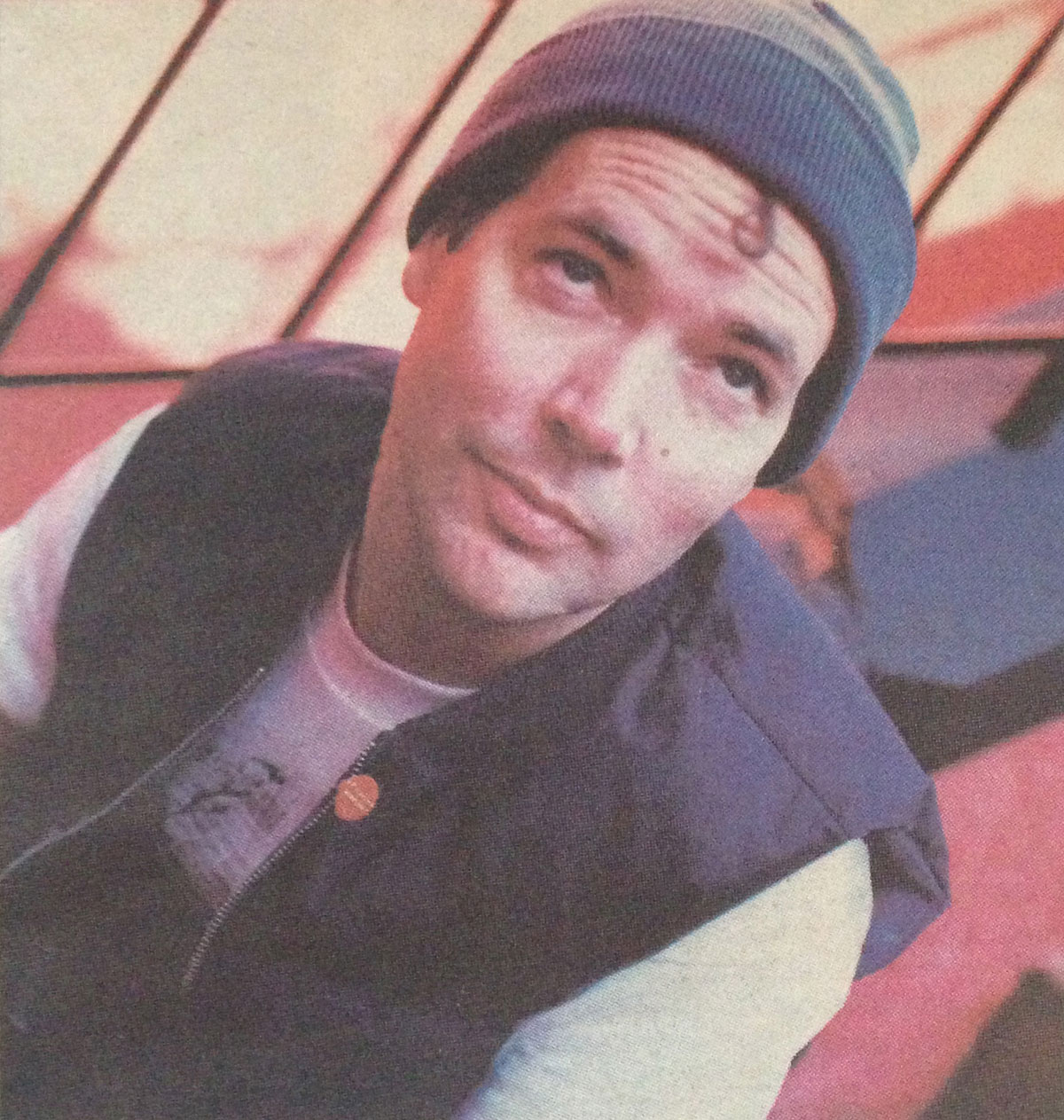

Phillip Smith and I had fifteen minutes to interview and photograph Coupland at a restaurant across from the Art Gallery of Ontario, which, combined with his already frenetic Coupland-like personality, made it probably the most enjoyable, bizarre, and memorable interview I’ve ever done. I considered this the best thing I’d ever written for quite a while afterward. It probably was. Here it is, almost exactly as it appeared in the Varsity newspaper, on September 29, 1995.

“What do you want from life?”

If anyone but Douglas Coupland was sitting in front of me, I might consider the fact that he has started our interview by asking me a question an attempt to control the conversation. But the way he asks, I believe he is genuinely interested, and likely asks it of most people he meets.

He seems taken aback by my answer (Coupland’s next book will be very different indeed), and continues by saying he doesn’t understand how people can know early on what they want to do for the rest of their life.

“When I started writing, it was just a way of paying the bills,” he says. “I need a new drill. I’ve got to pay the rent. I’d better write something. If you asked [in my twenties], I’d say ‘I’m a sculptor.’”

Coupland was indeed a sculptor in his earlier days, writing only occasionally for various Vancouver-based magazines. When I ask if he ever regretted his decision to leave the art world behind, he quickly becomes preoccupied by the decorative paint splattered purposely on the top of our table, which he tries to scrape off with a dinner knife.

Upon further questioning, he says he has no regrets concerning his eventual career choice.

“When you’re thirty, you have to choose one thing to do with your life,” he says. “People don’t respect you if you want to do more than one thing. [Sculpturing] wasn’t what I wanted to do. It was what I thought I wanted to do. I guess if you do what you want, even if you’re not making much money, you’re definitely happier.”

Coupland is in town promoting his fourth book, Microserfs, the tale of a group of Microsoft employees who give up their secure, albeit dull, lives of working for would-be world dominator “Bill” to go into business for themselves.

Although he is appearing as a part of the University of Toronto Bookstore’s reading series, Coupland will not be “reading” from his latest work this evening. Ironically, he will be showing a film, entitled Douglas Coupland: Close Personal Friend.

“It’s like the Charlie Brown Christmas tree of films,” he says. “When I was working on this book, I knew I couldn’t read aloud from it. So, what could I do? Talk about my day? So I called Jen.”

Jen being Jennifer Cowan, the film’s director, who Coupland had first worked with several years earlier on an installment of Citytv’s MediaTelevision.

“I don’t like doing television,” says Coupland. “I did too much TV. You come out of it feeling bruised. But, out of all the people I worked with, Jen got the point.”

Together, the two produced a semi-scripted “interview” with Coupland. The result resembles an issue of Wired magazine come to life.

We couldn’t pay [the crew] much, so we let them do whatever they wanted, which was a big risk,” says Coupland. “They might have been in a White Album phase: ‘I wanted to say everything and nothing.’”

I ask Coupland if, as an author, he feels like an outcast in an age where films (such as The Breakfast Club, in the eighties, and Reality Bites, in the nineties) more than any other genre, seems to hold a monopoly on defining the era in which we live.

He then reaches across the table and picks up my Ray-Bans with his left hand and his own identical Wayfarers with his right. He looks as though he is about to use them as a part of a visual demonstration to explain how film and literature are similar, yet different.

“I bet if we mix these up we won’t be able to tell which is which.”

After proving him wrong, I re-ask my question.

“I just do what I do,” he says. “It’s not a conscious thing. The books I’ve done start from a curiosity and go from there. If I’m going to write a book from a trend, it’s doomed. My books are imagine-based.”

At this point, less than fifteen minutes into our interview, Coupland’s publicist runs into the restaurant we are seated in and tries to rush him off to a sound check at Convocation Hall, where he will be not reading in three hours.

With time for only one more question, I decide to ask Coupland about an essay he wrote for the June issue of Details magazine, titled “Generation X’d.” In it, Coupland calls for an end to the misrepresentation and media-hype surrounding the phrase popularized by his 1991 book of the same name.

Coupland’s essay cites three early-nineties events in the major artistic genres as sparking the generation X frenzy: his book, Richard Linklater’s film Slacker, and the Seattle explosion of grunge music.

“The problems started when trendmeisters everywhere began isolating small elements of my characters’ lives and blew them up to represent an entire generation,” the piece read. “The result? Xers were labeled monsters.

“And now I’m here to say that X is over. . . . Kurt Cobain’s in Heaven, Slacker’s at Blockbuster, and the media refers to anybody aged 13 to 39 as Xers. Which is only further proof that marketers and journalists never understood that X is a term that defines not a chronological age but a way of looking at the world.”

“It just seemed like the right time to write it,” Coupland says. Before he can elaborate, however, we are forced to hurry out of the restaurant so he can make his sound check.

We rush to snap a few shots of Coupland on the stairs outside. He feels he would like to wear my sunglasses for the photo shoot, again to see if the two pair can be told apart. This is the last I see of them. (Although, in fairness, I managed to swipe his.)

As he stands up, I notice the picture on his T-shirt through his partially open vest.

“Is that the Unabomber,” I ask.

A very wide smile spreads across his face as he opens the vest and reveals what is indeed the now-famous police-composite of the “Weird Al” lookalike. The significance is lost on me until I hear the story he relates later that evening.

Coupland does decided to read at Con Hall, although not from Microserfs. Instead he reads three other short pieces he has written in the past twelve months, one of which is a thesis presenting O. J. Simpson, Bill Gates, and the Unabomber as the three main media focuses of today’s society.

Coupland’s film is better seen than described. Not a documentary-type interview, it more closely resembles a film version of one of his books, with him as the star, and speckled with clips from nineteen-sixties and seventies television commercials. Actually, many of the pop culture comparisons Coupland makes to life in the nineties are taken directly out of the mouths of his characters.

Seeing this reminds me of one other question I had asked Coupland earlier that day. Given that he is so quick to point out the problems and complexities of today’s world in his books, I wonder if he feels he is, at the same time, providing any answers.

“Yes,” he says, but will not elaborate.

“They’re there, but they have to be found.”