They pour from their offices into elevators, which carry them down to the lobby, from whence they crowd into revolving doors and spill out onto the sidewalk. On hands and knees, their snouts pressed hard against the pavement, their ears alert, they proceed home. When I say “they,” I mean “we.” We sniff the sidewalks and catch a bit of ourselves from earlier in the day, and the scent of urine and chewed gum and leaves that have drifted down from the trees. We love our jobs and we love autumn. Our hearts are big.

I stepped into the supermarket and walked through the aisles, sidestepping careening shopping carts and towering displays of baked beans. A piece of paper in my back pocket contained the words “canned tomatoes,” but I didn’t need to consult it. However, when I reached the pertinent shelves, a cow blocked my way, waving her tail. Two grocery clerks pushed at her haunches, trying to move her along, but she wouldn’t budge. I couldn’t get to the canned tomatoes. The cow mooed. I decided to pick up a pizza on the way home.

At an intersection, waiting to cross, I turned to a man beside me. He looked dimly familiar. I was convinced he was my Grade 7 geography teacher’s son, because he was the same age as me, and so could not be my Grade 7 geography teacher. “A cow stood beside the canned tomatoes,” I explained. “Nobody could move her, and nobody knows how she got there. I’ve changed my dinner plans.” As I got closer to my home, a boy was playing hopscotch on the sidewalk. I kicked him, and he tumbled into the street.

I had a pizza in my hands. The elevator door in my building opened. There were five of us waiting to board the elevator, but a cow stood inside, taking up all the space, and likely using up the legal weight limit for the elevator. “His name is Otis,” said a woman I often saw in the laundry room. “No, Otis is the elevator’s name,” said a man I had never seen before. Fearing he was an intruder in the building, possibly responsible for a recent rash of break and enters, I kicked him, which made my pizza fall from my hands.

I gazed out my apartment window at the mountains. My stomach was empty. They were coming down, down from the snow-capped peaks. They were in the supermarkets, blocking the aisles, and they were in the elevators, making me walk up the stairs, which hurts my legs. I couldn’t recall whether or not I lived with anyone. “I’m home!” I shouted, but there was no response. In my bedroom closet, there was only my clothes. I fell immediately to sleep and dreamed that I lived with a girl who was in my Grade 7 geography class.

Shuffling barefoot out of my bedroom in the morning, wearing my red terry-cloth bathrobe, I heard music in the living room. It wasn’t a CD that I owned, because it had words, and I had no CDs with words. A cow is a four-legged mammal bred for its milk production and because you can eat it. One stood in my living room, gazing at my stereo system, mooing. The song the cow was playing was “Long Tall Glasses,” by Leo Sayer. After that song came “The Passenger,” by Iggy Pop. After that song came “Stumblin’ In,” by Suzi Quatro, and then “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” by Elton John and Kiki Dee. I did not understand how the cow came to be in my apartment, but it had eclectic taste in music.

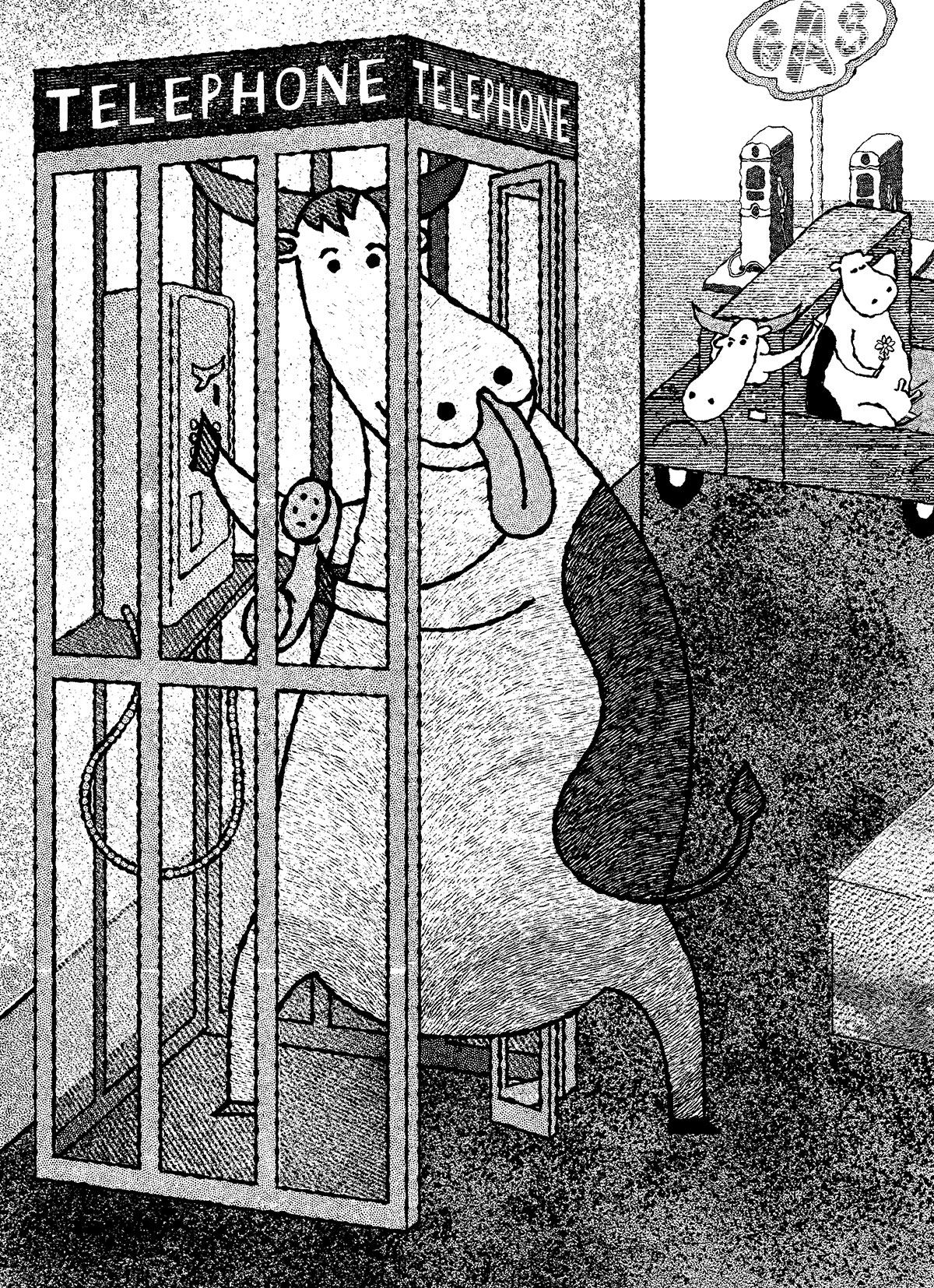

At the gas station at the corner, I waited by the telephone booth. Inside, a cow stood on its hind legs, its face pressed against the glass, looking at me. If it hadn’t stood on its hind legs, it wouldn’t have been able to fit in the booth. When I was in Grade 7, Murray Nightingale came to school with a cow’s heart in a jar. What surprised me was that the heart was white, not red. There was sediment floating in the water in which the cow’s heart was submerged. Murray’s father owned a slaughterhouse, and Murray was always bringing parts of cows to school. I hated when this happened, because it made me sick to look at this stuff. He once brought a cow’s eyeball, also in a jar. It looked at me like the cow in the phone booth was looking at me. I kicked Murray Nightingale.

On my way to the police station, where I wanted to report the cow incidents, I saw a boy lying in the street. Concerned for his safety, I pulled him up onto the sidewalk and lay him in a large rectangle formed by a chalk diagram. Children used this diagram for a jumping game called hopscotch. At the police station, an officer asked me to sit down and catch my breath. “First there was a cow beside the canned tomatoes, in the supermarket,” I explained. “Then there was a cow in the elevator at home, and we had to use the stairs. Also, a cow played music this morning in my living room. Most of the music was from the nineteen-eighties and the nineteen-seventies. When I went to phone you from the phone booth, there was a cow in the phone booth.” It was like a TV show in the police station. A girl wearing leg warmers looked like a prostitute, and some people were angry and there was a lot of “commotion.”

When everything was normal again, I felt a certain emptiness. I sat in my office and made big decisions, but it just wasn’t the same. I swung around in my chair and looked out the window, into the mountains. I knew they were up there, and when they felt the time was right, they would come down again. After work, on our hands and knees, our snouts to the pavement, the sidewalks didn’t smell right. We all looked at each other and agreed that the sidewalks just didn’t smell right anymore.

In the mountains, there was activity.