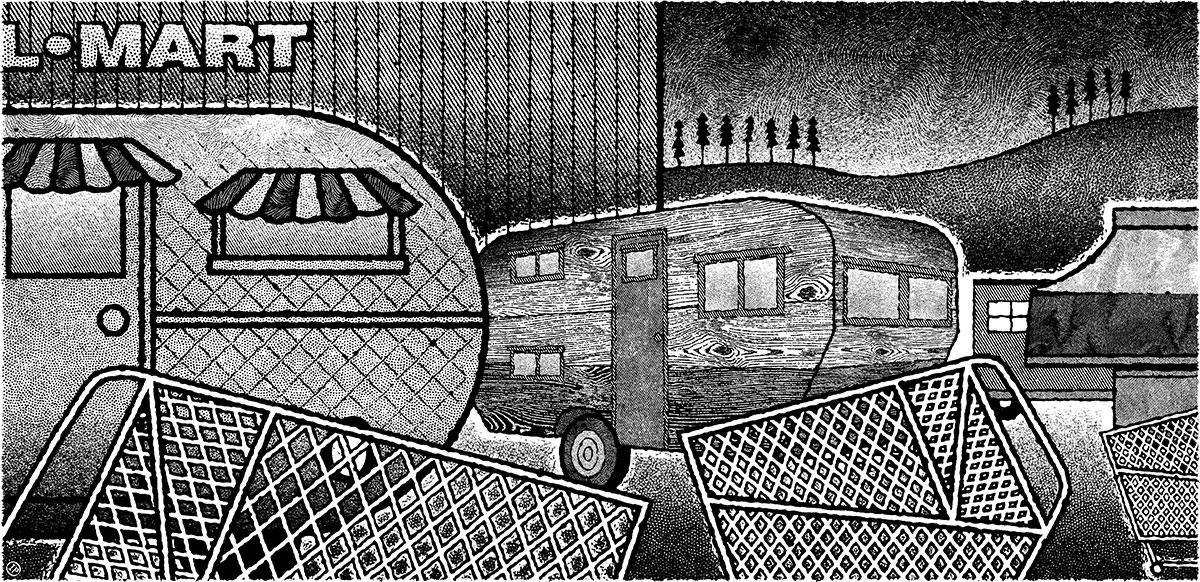

Eureka parked the Airstream too close to the garbage Dumpster and she’s too stubborn to move it, even though at night half the neighbourhood comes driving up with their headlights off to slip their trash bags in with Wal-Mart’s.

“I can’t believe it,” I tell Eureka. “Can’t these people wait for garbage day? ”

“Oh, Evelyn, it’s summer,” she says, as if I can’t smell that it’s summer, “and they probably got their garbage pickup cut to once a week.”

Eureka thinks nothing of changing towns once a week, taking her whole life with her, but she don’t think it’s strange that those people can’t handle a change in their garbage pickup. Eureka’s from the that’s-just-the-way-God-made-them school. It’s always, “Settle down now, Evelyn! No reason to get in a flap! That’s just the way God made that lady driver. She’s going places, that little lady. Nothing we can do about it.”

Mouth the words with me: “Nothing we can do about it. That’s just the way God made her.”

I’m gonna tell you something that Eureka doesn’t know I know. This is it right here: Eureka doesn’t even believe in God!

I wish I could really ask Eureka, “If you don’t believe in God, then who did make that little lady and all those fine people out there? ” But I can’t ask her, because Eureka is a recovering alcoholic, and to keep on being a recovering alcoholic, she’s not allowed to not believe in God. That’s why it’s a secret.

Eureka lets things be what they are. She’s really my granny, but she’s been watching me for years. I’m gonna be fourteen soon—as old as my mom, Cathy, was when I was born. When I was almost thirteen, Cathy said she was gonna leave town and take me with her—“Little Evvy” she called me, even if I’m taller than her now, I bet—so Eureka just walked out and started up the truck with the Airstream hitched on, and I hopped in right beside her, because ever since Eureka got to be a recovering alcoholic I’ve had to keep a close eye on her.

Our first night at this Wal-Mart, someone knocked at the door, and I started staring at Eureka like we were in trouble for sure. But she just waddled over, wiping her hands on her dress, and crouched down at the door with a friendly smile, and I could just see below her jiggly arm that a nice looking guy was there, and his girlfriend was waiting on his motorcycle. And he said, “Hi. I was admiring your trailer. You folks come all the way from the coast? I wouldn’t mind making you an offer if you’re thinking of putting down roots here. Always wanted an Airstream.”

I know this trailer is a collector’s item. When we stop in cities there’s people that always stare. They look at us like we don’t deserve it, too, just because Eureka’s so wide and I’m, whatever, scrawny, or maybe I don’t wear makeup so I don’t look like a model yet, which is what I’m gonna be when Eureka lets me. Eureka’s careful, and that’s why the Airstream still looks so nice, and still a bit shiny, and not hardly dented, and why I’m not a model yet. I know those people might look nicer than us with an Airstream trailer, but that don’t bother me, because one day I’m gonna look nice too, sitting here, right here, all alone in the driver’s seat, hauling this hunk of aluminum all over the country.

The other time my mom said she was gonna take me and go somewhere, just me and her, and Eureka said, “No way, Jose,” in her calm voice like vanilla pudding, Cathy yelled real loud, “It’s my goddamn, God-given right,” and Eureka said, “There ain’t no such thing.”

That was my first clue. After that, I watched Eureka pretty close. We are not the only people in this parking lot. There’s a family with a tent trailer across the lot. They shop all day and put the tent up at night. They never seem to buy anything, but I’ve seen them waiting for the doors to open in the morning.

I think our truck has broken down again. We’ve been camping here for six days now, and the only time Eureka stays somewhere so long is when there’s no gas or the engine’s busted. Mostly she’ll find someone, maybe someone from the back warehouse or a hardware store, or one time it was a guy from a slaughterhouse, someone who knows about motors, and they’ll just fix it for her. She says big men like big engines and they’re happy to help. She sends me shopping or walking a while, but I know what’s up. First they tinker with the engine, then they fiddle with Eureka.

Eureka says we might have to go meet those people with the tent trailer, because it would be the neighbourly thing to do. I just look at Eureka like she’s nuts.

O.K., I’m gonna tell you a sad story and it’s totally true. There’s two girls living in that tent trailer with their dad and his girlfriend, and they never, ever, if you can believe it, lived anywhere else. Jennifer told me. She’s nine, which isn’t as bad as it sounds.

Eureka made me go and talk to them after I got back from the store. She always sends me shopping when we need toilet paper or cheesy crackers or whatever. She always says I’m so skinny that if someone looks at me I should just turn sideways and I will disappear. That’s not true, though, because my shopping jacket is pretty baggy.

When I got back from Wal-Mart, those girls’ dad was by the Airstream. Jenn and Reba were hanging out, staring at me, and Eureka said all happy, “Evelyn, honey, these girls can’t wait all day! Off you go back to the store with them and have yourselves a nice time.” She looked like she was gonna give me some money, but she just squeezed my hand.

Jenn says her dad’s girlfriend sleeps all day in the car and her dad always says not to wake her. How can someone sleep all day for nine years in a row?

There was another clue right as soon as we stopped in our first town. Eureka left the keys in the washroom at the truck stop and a lady came running out after her—actually a real lady with little heels and a little jacket that matched her dress—and after she gave the keys to Eureka and Eureka opened the truck door, the lady just stood there looking at her and at me. Then she reached into her purse and pulled out the Holy Bible, and she said in her pretty voice, “In the Scriptures, the good Lord tells us—” And Eureka didn’t even let that lady finish. She just climbed in and closed the door.

Jenn is tiny. She’s almost as short as Reba, who is only seven, but she’s smarter. When I ask her, “How come the shopping carts don’t roll down the moov-a-tor? ”—that’s what she calls the flat escalator that goes to the basement level—she looks at me like I am so dumb. I say we should go down and up again so we can make sure Reba isn’t following us. But really it’s so I can get another look at the wheels on those carts.

Halfway down, I stretch my arms out along the moving handrail and say, “I’m going to be a model, you know.”

“You’re too short.”

“Eureka thinks I’m tall as anything,” I say.

“You just think you’re tall because your dress is too small,” Jenn says. “Your sleeves are too short. Your arms hang out like a monkey. And I can see your underwear.”

I drop my arms and hold my dress lower. I’m mad at Jenn now. I forget about the shopping carts. I move my eyes around, looking for a mirror. At the bottom of the escalator, Jenn walks off first. It takes ages for us to pass a mirror, then all I see is my face, looking almost like a crybaby.

Jenn stops in the girls’ department and smiles at me. “Let’s pick out something nice for you.” She smiles at me for a long time.

I want to hug her.

I hardly even look at the dresses Jenn points out. I’m thinking I could live in that trailer with her, and she could dress me up and go to model go-sees with me. She could even sign my pictures for me, the ones I send to boys who write, if they write nice things. I keep on thinking about it all the way up to the main floor. I don’t even know which dress Jenn has under her sweatshirt when we burst out into the parking lot. She’s giggling, so I do too.

In the Airstream, Eureka is sleeping. I strip down to my underpants and Jenn helps me wiggle into my new dress. It’s navy blue, with pleats that start at a white ribbon below my chest and go all the way down. The hem zigzags just above my knees. Jenn closes the buttons in the back then stands behind me without saying anything. I don’t know what to say, either. I can feel Jenn’s breath on my neck. I can smell the sweat from her. My arms are locked to my sides, pressing everything inside me into a tight, hot bundle. It takes me a minute to realize that Jenn is holding them there. The insides of her elbows are damp where they cross over my arms. Her hands are flattening the pleats over my belly. Her little body is pressed against mine and the posts of the buttons are pushing into my back, up and down my spine. It takes me a minute to really know all that.

By then, she’s already out the door.

This morning the stink is gone from the Dumpster, just like that. It’s a cool morning, a bit windy. Eureka says we’re leaving. It’s my birthday, but Eureka’s tired. She woke up and said she feels old today, but she didn’t say, “How you feeling, Evelyn? ”

She didn’t notice that I’m older today.

Across the parking lot, Jenn is sitting on the hood of her car with her legs dangling down. Reba is sticking stones in Jenn’s sandals, under her toes, and Jenn’s feet are jumping.

Jenn slides off the car and Reba begins to run. Jenn runs after her. Their mouths are open. They are laughing. They look very far away.

Eureka turns the key and the engine starts up. I’m still standing at the Airstream window in my nightgown when we start to move.

I think I will stand here all day today, like a photograph going by. I’ll take a marker and write on the window: “MISSING.” Let Eureka drive up front while my face and my word flash by all the people on all the sidewalks.

Years from now, those folks will still be looking for me. They’ll see my real picture, my model picture, and say, “I’ve seen her face before; before she started wearing that navy dress.”

The dress is under my mattress. It’s flat, still asleep.