Maugerville’s Big Potato Man has been charming locals and tourists for more than half a century.

Last spring, a Facebook friend of mine posted a photograph of a white plastic shopping bag adorned, in green, with a smiling anthropomorphic potato and the words: “Fresh Vegetables from ‘the potato man.’”

I quickly did a Google search that confirmed my hope: Harvey’s, the Maugerville, New Brunswick, vegetable stand listed on the bag, was indeed home to a four-limbed, top-hatted giant smiling potato.

I spent my first eighteen years living an hour from Maugerville, but somehow, until that moment, I’d been completely unaware of this Eighth Wonder of the World. So, last July, I flew to Saint John, got in a car, and drove the hundred and twenty kilometres to Maugerville, a small community on the east bank of the Saint John River, just outside of Fredericton.

Maugerville (pronounced “Majorville”) is located in Maugerville Parish, in the county of Sunbury. On a map, Maugerville Parish, home to fewer than two thousand people, looks like a narrow, rectangular lot that juts eastward on about a forty-five-degree angle from the river. The portion of Maugerville most non- residents see is its approximately twenty-kilometre- long southern border, on Route 105, which runs along the river’s east bank and features a handful of homes, a few farms prone to flooding, and Harvey’s Big Potato, a long wooden structure with a cement floor, a high peaked roof, and horizontal slat siding.

Whether you pass through Maugerville from the east or from the west, you’ll be greeted by the Harvey’s mascot, known only as Big Potato Man—a twenty-foot-tall spud with spindly stick-like arms, somewhat thicker legs, a black top hat, and the same smiling face on either side of his “body.”

I arrived less than an hour before closing and met the proprietor, Daniel Boudreau. For the past few seasons, Boudreau has leased the stand and its adjoining farm from Buzz Harvey, the grandson of the original owner. “Last year was our first year growing,” Boudreau said. “Potatoes, corn, peas. We’re trying to see if we can make it pay.” I asked him about Big Potato Man. “Probably twenty, thirty, people a day come by to take a picture of him. Most of them buy something. Even in springtime, when we weren’t even open, there’d be twenty, thirty cars a day.”

Buzz Harvey retired in 2015, at the age of sixty-two, but still lives on the farm next door. Boudreau offered to invite Harvey to join us and telephoned him. A few minutes later, Harvey pulled up in his truck, dressed in hiking boots, beige shorts, and a plaid button-up shirt, with a ball cap over his white close-cropped hair. “The original farm here was about fifty acres,” Harvey told me. “We added another hundred and fifty over the years, and I sold some off. Now it’s about seventy- five acres. My grandfather bought the land in 1921. I think it was up for tax sale. It was a farm when he bought it. I don’t think they were growing much. He started the roadside market in 1952.”

By the late sixties, Harvey’s father was running the farm and decided business might be improved by the addition of a roadside attraction. “We were going to put two corn cobs there,” Harvey said. “We were known for our corn. And Dad said, ‘Well, the background of the business for years and years has been the potatoes’—the Green Mountain potato. So he said, ‘Let’s make a potato man.’ We hired someone to design and build it. My dad was a flying instructor, and he’d taught the artist to fly. His name was Winston Bronnum.”

Winston Bronnum, circa 1960.

Winston Bronnum was a well-respected, somewhat renowned artist, particularly in his home province. He had a practical attitude toward the intersection of art and commerce. Bronnum once referred to his career as “more a commercial venture than an art venture,” and said, “I get a lot of pleasure out of it but I like to eat well while I’m doing it.”

Bronnum was born in 1929 and grew up in New Denmark, a rural community in New Brunswick’s Victoria County, south of Drummond and about twenty minutes east of the Maine border. New Denmark is known as both the country’s oldest and largest Danish settlement, and its main industry is potato farming. Bronnum frequently got into trouble as a child for carving horses into the pine desktops at his school. Most accounts of his life say he dropped out during the Second World War to help work the family farm, though a few say he was thrown out for his artistic destruction of property. As a young man, he moved to Ontario to work in construction. Bronnum had a natural engineering ability and soon he was supervising rigging on hydro dams and bridges. He continued honing his carving abilities and, in the nineteen- fifties, returned to New Brunswick and opened a studio, first in Grand Falls, then in Fredericton. His sculpted animals, usually local woodland species, of which he was fond, became popular with hunters and tourists. Bronnum’s reputation quickly grew, both as an artist and an eccentric personality. A local paper once described the familiar site of Bronnum’s “maroon- colored station wagon with a horse’s head carved out of wood as a hood ornament, a pair of hands holding chisel and mallet sculpted against a maple leaf and the name Bronnum inscribed on either side.”

Bronnum’s commissions and selling ability grew with his reputation. For Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, he carved a coat of arms to hang in the Historic Beaverbrook House. His work was displayed in New York’s Waldorf Hotel and Rockefeller Center. In 1953, Bronnum spent sixteen days carving a memorial plaque of the royal coat of arms, to commemorate Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. He then sold replicas, created by pouring plaster of Paris into a rubber mould, which the Moncton Daily Times said Bronnum felt “would make suitable memorials in public buildings.” He began incorporating his engineering skills into his art and developed a technique of modelling Portland cement reinforced with steel to create sculptures that withstood the ravages of nature. Bronnum regularly created floats for the Moncton Santa Claus Parade: One year, he built a nursery-rhyme-themed twelve-foot-high old shoe made from eleven hundred feet of fibreglass, six hundred pounds of steel rods, and thirty gallons of paint; another year, his float consisted of a twenty-four-foot-long rooftop crowned with Santa’s sleigh and eight animated reindeer. And until the redevelopment of Saint John’s Haymarket Square, in the nineteen-seventies, a life-sized horse carved by Bronnum sat for many years on the roof of the city’s Gladstone tavern. When the horse was offered at auction, years later, the auctioneer marvelled, “Why, look at his nostrils and feel the conformation of his hips. You know Bronnum really studied animals.”

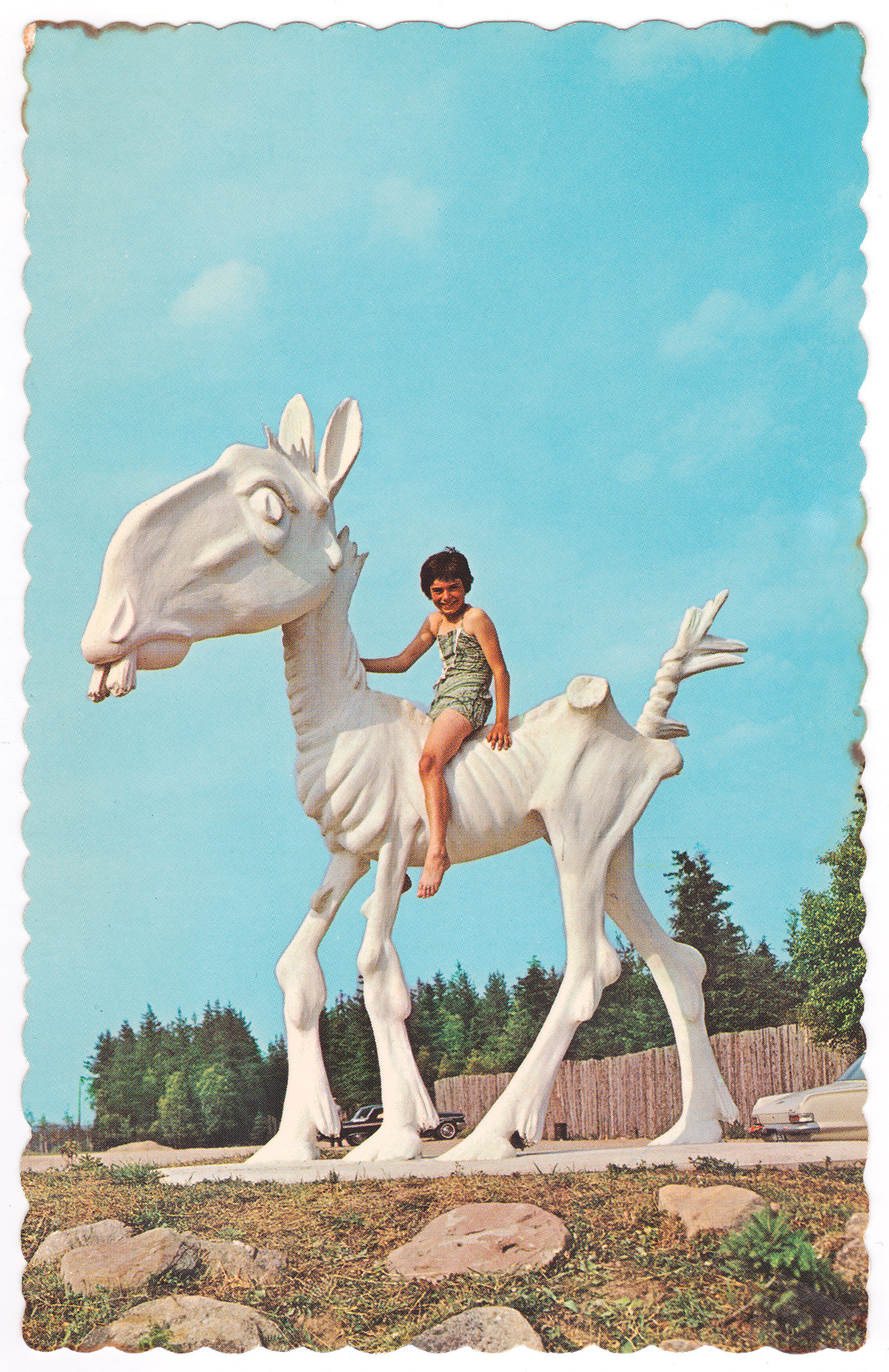

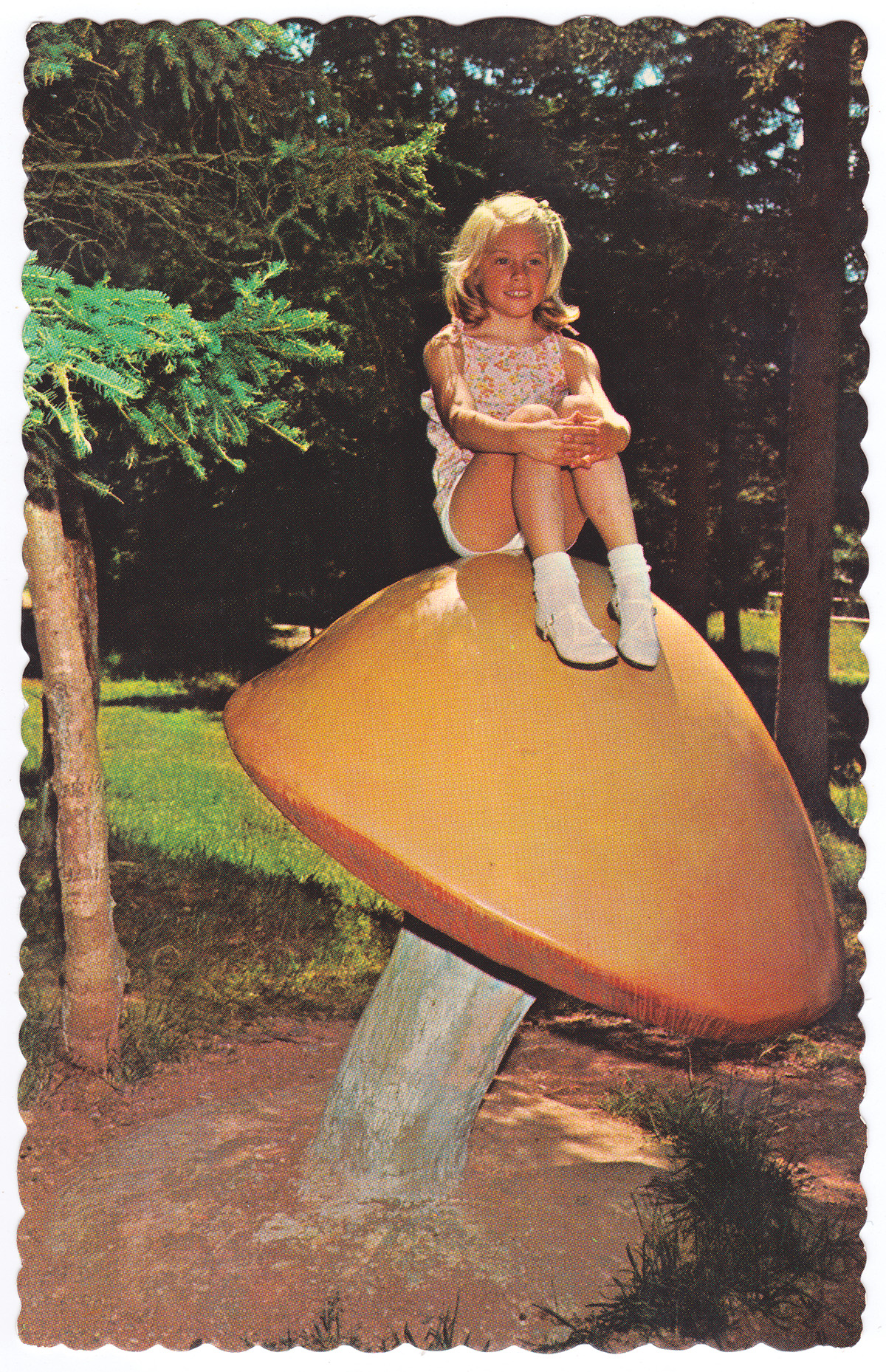

Blow Hard, Animaland’s racehorse mascot, still greets visitors today (top). The park’s play area featured rugged, climable statues for kids.

Bronnum’s most substantial wildlife tribute was not a single sculpture but a garden full of them. In the nineteen-fifties, he began work on Animaland, a nineteen- acre amusement park, near Sussex, along what was then the Trans-Canada Highway. Blow Hard, a white, skeletal-looking racehorse, welcomed visitors at the entryway and acted as the attraction’s mascot. The park eventually featured dozens of additional life-sized sculptures—Bronnum added to Animaland for years—including bears, a giraffe, a lobster, and an octopus. It also included a playland, with animal statues children could climb, a gift shop, and an aquarium, featuring real-life sharks. Animaland shuttered shortly after Bronnum’s death, in 1991. It sat derelict for years but recently started attracting an increased number of curious trespassers, some old enough to be drawn in by nostalgia, others young enough to be intrigued by the park’s legend. In 2016, the friends of Bronnum who bought the park after his death reopened it as a campground, leaving all of the sculptures in place. Ulie Fournier, one of the owners, said his reasons for reopening after so long were partially to take advantage of the asset but also to avoid the growing liability issues. “There’s no real financial gain,” he told the Telegraph-Journal. “The real issue was people assuming it was abandoned and coming in here and vandalizing and taking advantage of it. We just didn’t want to be subject to it anymore so the only way to do that is to have fun.”

Bronnum’s humane tribute to Jumbo, in St. Thomas, Ontario.

In 1882, P. T. Barnum, the legendary American showman, purchased an elephant named Jumbo from the Royal Zoological Gardens, in London’s Regent Park, for the sum of two thousand pounds. Jumbo was nearly twelve feet high and weighed seven tons, earning him the title of the world’s largest elephant. Jumbo was not named after a word for big things—big things were named “jumbo” after him. The sale didn’t sit well with the British public, who saw the elephant as a national treasure. Despite protests, the transaction went ahead. Jumbo was transported by ship to his new home, in New York, and became the star attraction of Barnum’s travelling circus. Over the course of the next four seasons, Jumbo travelled tens of thousands of miles across North America, warming audience hearts through his impressive size and gentle nature, and earning, in Barnum’s estimate, more than a million dollars.

On September 15, 1885, Jumbo and a smaller elephant, named Tom Thumb, were being led along the tracks just outside of St. Thomas, Ontario, when an unscheduled Grand Trunk freight train struck them both from behind. The engine pushed Jumbo a hundred feet, and he died within minutes. Barnum continued to profit from Jumbo after the elephant’s death, taxidermizing his hide and displaying it alongside his skeleton for several more seasons. The residents of St. Thomas eventually found a humane way to profit from and pay tribute to Jumbo. Ideas for a monument were first suggested soon after the accident and again on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary, in 1935, but nothing materialized. Finally, in the years leading up to the centenary of Jumbo’s death, citizens and the local Kiwanis Club raised enough money to hire Bronnum to create a life-sized effigy of Jumbo. The statue’s steel frame weighed six thousand pounds and was encased in thirty-four thousand pounds of concrete, making it several times heavier than the real Jumbo. Bronnum spent more than a year researching—including time at the Ringling museum, in Florida—and one year building the work before it was transported, in pieces, along the Trans-Canada Highway, to St. Thomas. Not long before the statue’s unveiling, in June of 1985, Bob Stollery, chairman of the St. Thomas Jumbo Monument Committee, said Jumbo’s death was “about the only exciting thing that’s ever happened here.” Bronnum sold the event with a little more Barnum-like flourish, telling the Telegraph-Journal, “The commission to do a life-size African elephant for the folk of St. Thomas was a challenge, yes. I had thought and worked mostly in terms of the smaller creatures of the New Brunswick woodlands. But an elephant? That was something else. Despite his tragic death, I have given Jumbo the up-raised trunk. That’s traditionally the good luck elephant.”

Bronnum considered the Shediac Lobster “probably” one of his best works.

Bronnum completed one last major work the year before his death, at the age of sixty-two. In the nineteen- eighties, a group of Shediac Rotarians attending a convention became enamoured with the eight-and-a-half-metre-long steel salmon located on the Restigouche River waterfront in Campbellton, New Brunswick. The statue, known as Restigouche Sam, was created as a symbol of salmon’s importance to the local economy. The club brainstormed ideas for promoting Shediac as the world’s lobster capital and eventually commissioned Bronnum to create a thirty-six-foot-long, sixteen-foot-high, eighty-ton lobster. (Bronnum’s lobster often is said to hold the Guinness record for the world’s largest lobster, but it does not.) Bronnum said the piece was the largest he’d ever created and “probably one of my best.” He built the sculpture over the course of two years at the four-thousand-square-foot studio he maintained at Animaland. “The artist began by studying lobsters while wintering in Florida, videotaping them as they flitted about in a glass tank,” reported the Moncton Times-Transcript. “He used an embalmed creature as a reference point. The massive Shediac beast started out as a pencil sketch, evolved into a 30-inch model made of clay, styrofoam and wire, ‘and from that I went on to the real thing.’”

The statue was moved by flatbed trailer to Shediac’s Rotary Park and secured to its sandstone base in time for the 1990 Canada Day weekend. In 1987, the club estimated the statue, base, and surrounding park, all told, would cost about two hundred and sixty-five thousand dollars. This sum was large enough that construction was put on hold for a year while funds were raised and critics were quelled. At the time of its unveiling, the reported cost had risen to more than three hundred thousand dollars. When the lobster, which draws five-hundred-thousand visitors a year, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary, in 2015, the total original cost was reported as four hundred thousand dollars. Bronnum brushed off criticism of the price, reportedly saying, again with P. T. Barnum flourish, that he was giving the town a concrete lobster at a rate “cheaper per pound than real lobster would cost.”

In 1953, the Telegraph-Journal reported, “Wooden potato samples, so perfect they have been okayed by Ottawa potato experts as exact reproductions of New Brunswick spud varieties, have been carved by Winston Bronnum, the artist.”

In a career filled with oddities, Bronnum’s Big Potato Man is possibly the oddest. “My father asked Winston what he could build for a thousand dollars,” Buzz Harvey told me last summer. “So, he started in the fall of ’68. He put the base in, and Winston worked on it in his shop, in Sussex, and he brought it up and placed it, and then he coated it. It’s about four to five inches thick. They had a plastic thing around it, and they unveiled in on July 1 in 1969. I did a facelift three years ago. It needs another one. We didn’t do much to it the first thirty to thirty-five years. When we put it up, we doubled our business. The Americans all call him a peanut—Planters peanut. Probably because he’s a blob. He’s the shape of a Green Mountain potato. It’s a variety that originated around 1880, 1890. A white potato. Closest to a Kennebec. It’s dry. The old fellas around here like their potatoes dry, dry. They’re good for everything. We used to French fry them. They’re high in sugar, so they brown up.

“My father was around when we had a twenty-fifth anniversary for the Big Potato Man. We reduced everything to 1969 prices for the day. It was probably our biggest day ever. We’re thinking about doing something for the fiftieth. I don’t know what yet. We never really got promoted by New Brunswick enough. It’s kind of a shame. Idaho said they had the biggest potato, but we have the biggest in the world.”