Mr. Roldo thinks that X-rays show he has no heart.

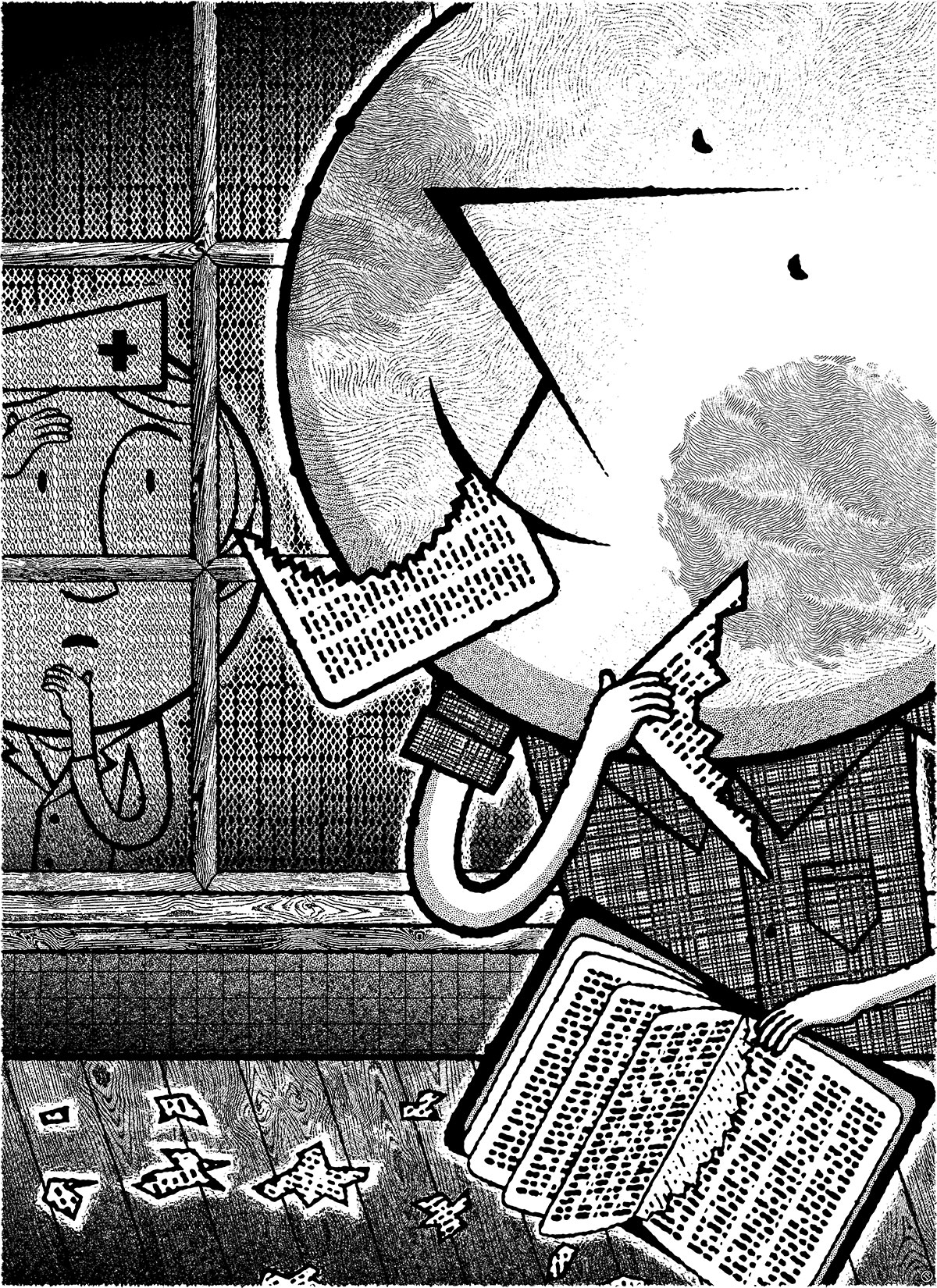

Markus eats bibles, page by page. When he is completely done an entire bible, he starts on another.

Noodle starts a dance every morning in honour of her dead father, but after breakfast she sits in front of the TV and watches Markus eat.

Meg is the nurse here. She has a bumper sticker on her beat-up convertible that says, “BE KIND TO YOUR CHILDREN. THEY ARE THE ONES WHO WILL CHOOSE YOUR NURSING HOME.” She often wonders why some of the words are capitalized and others aren’t. “Who chooses that?” she thinks. “Who makes all the decisions?” Meg doesn’t like to make decisions, and so she can’t fathom, even for a moment, who makes the complicated ones.

When Noodle first moved in, she had spaghetti in her hair. Mr. Roldo picked it out and ate it. His motions were soft and soothing, calming. But Noodle became so agitated that Meg had to lock her in her bedroom and put on the lullaby tape in the office. She had to project the sound down the hall, and so she pulled the tape recorder out of the office, the cord taut, and tilted it toward Noodle’s room so the hush-little-baby noise would settle down the screaming. Meg used to do that for her mother. She used to hum sweetness into her mother’s ears when the world was so close it hurt her mother to think of it.

“You’re all in a noodle,” Mr. Roldo said.

“Holy, holy, holy,” Markus said. “The Lord Almighty is holy!”

And Meg shuffled on her swollen feet, back and forth, from the office to Noodle’s room to calm her, back and forth.

Every morning, Markus starts with a new page. Then he visits the washroom down the hall. Then he goes to the TV room, settles in, and tries another page; swallows hard to get it down.

Even though she’s in charge, Meg always wonders why. She doesn’t know what to do half the time, and there are moments, lying in bed in the dark, her nightgown twisted around her stout form, that she thinks she might be the crazy one and the others are the nurses. Meg can imagine Markus as a nurse. He has eaten so many bibles in his fifty-two years that the words of good seem stuck to his ribs. It’s as if he’s become one with the morals.

“When the Lord your God gives you victory in battle and you take prisoners, you may see among them a beautiful woman that you like and want to marry,” Markus says. Even though Mr. Roldo has no heart, he takes a moment to be still and contemplate.

The Good News Bible Markus is working on is 1,138 pages, not including the map, chronology, word list, and all the other forwarding pages.

“Do you ever start from the back and eat forward? ” Meg asks.

Markus’s mouth is full.

Noodle says Markus hasn’t ever read the bible. She says that he wants to get into heaven just by ingesting it. And then she wonders aloud what ingesting means and whether you can out-gest.

Today, they are going on a field trip. Meg locks up the home. She wants to tie them all together with rope to make them stay safe, like little children, but, instead, she has them each hold hands. Meg holds hands with Markus, and Mr. Roldo and Noodle take hands and walk up front. Over the parking lot toward Meg’s car they walk, the other patients in the other scattered homes throughout the compound around the asylum look out the windows.

“We’re going on a field trip,” Noodle shouts. “We’re escaping.”

Meg requested this field trip several weeks ago when she saw the weather turning golden and clear. She asked Doctor Mayburn if she could take them out, just her three charges, into the sunshine, away from the home. Doctor Mayburn wondered about the request for awhile, the long fingers of one hand holding his chin as if his mouth might fall open. He smelled of wine and garlic, a cheesy smell lingering behind him somewhere. There were gnats above his head. Meg thought to herself, “There’s a peach pit rotting somewhere in this room. I just know it.”

And now they are in Meg’s car. Markus is belted into the back seat next to Mr. Roldo, and Noodle sits shotgun next to Meg. Meg starts the car.

“Once, I was looking out the window of my house,” Markus says, “and I saw many inexperienced young men, but noticed one foolish fellow in particular.”

“Oh? ” Meg says, grinding gears. “Which house was that? Your childhood home? ”

“He lived all over the world,” Noodle shouts. “He told me before.”

The convertible shoots forward and back, Meg’s foot heavy on the clutch.

“Let’s take the roof down,” Mr. Roldo says. “Not that I would care at all, but it’s a beautiful day.”

Meg pulls over by the exit to the Better Living Mental Asylum sign. “PLACE YOUR LOVED ONES WHERE THEY ARE CARED FOR IN STYLE,” the sign states. “AFFORDABLE YEARLY RATES. GOOD DOCTORS. LIVE-IN NURSES. PATIENT TO NURSE RATIO AVERAGES 4 TO 1.”

Meg sighs. Four to one until someone dies, she thinks. Then it’s only three to one. Better deal for your money. She gets out of the car and starts to struggle with the roof.

Noodle begins to push the buttons on the radio. Billie Holiday sings the end of “Fine and Mellow,” and then “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good).”

“Billie has heart,” Mr. Roldo says.

Meg remembers back when she was little. When her mother used to take her to the dances at the recreation centre down the street from her house. All the little babies screaming in the corner while the mothers danced until dawn. And Meg was in charge of the babies. Again, she didn’t know what to do. She’s never known what to do it seems. Meg would change one diaper and the next until, suddenly, she was changing only clean diapers, her fingers flying over open safety pins, and the babies kept screaming and spitting up and wanting their mamas, and Billie Holiday was singing heartbreak and sorrow all night long.

Meg gets back in the car.

“Where are we going again? ” Markus asks. “I want to make sure I brought enough to eat.”

“You’ve got an entire bible, Markus,” Noodle says. “That takes you a month, doesn’t it? ”

“We’re only going out for the day.” Meg turns left out of the exit and heads south to the beach.

“Good God, it’s fine to be alive,” Markus says. He chews on the bits of paper stuck to his teeth.

But Meg has been wondering lately if it is fine to be alive. She’s been shuffling with swollen ankles, edema from too much salt and improper shoes, back and forth down those hospital halls for over twenty years now. She’s lived in that room next to the kitchen, one tiny room, for fifteen years; moved in to take care of her mother, just after the debt collector took the house and furniture, took everything but the tiny yellow dresser in Meg’s room. Her mother died last year. In the asylum. Died with her head in Meg’s lap. And Meg’s been with Markus for eight years, with Mr. Roldo for six years, and with Noodle from the moment her daddy died in her arms, one year and three months ago. Noodle, the tiny little woman with the big head and hollow eyes. Her dance every morning is eerily perfect. It is noiseless with large movements and pained facial expressions. She dances to the music in her head.

But Meg wonders if dancing sadly is enough. She wonders if helping others is enough. When, she asks herself sometimes, will someone help me?

Meg pulls over in the parking lot at the beach.

“This,” Mr. Roldo asks, “is it? This is where we are going? ” He spits.

“We’re going to walk the beach,” Meg says. “We’re going to get some exercise.”

Mr. Roldo holds his chest as he gets out of the car and starts to walk down toward the water. X-ray after X-ray, but nothing will convince him that he has a heart. “Hear the beating, Mr. Roldo,” the yearly doctor says during checkups. “Hear that bumpity-bump? That’s your heart, man!”

“That’s indigestion. That’s a piece of fruit travelling through the stomach. That’s bile turning in my chest.”

“There’s no bile in your chest, Mr. Roldo. Just a healthy heart.”

Of course, if Meg were to think about it, she would liken the old man’s failure to admit he has a heart to the fact that his wife is dead. No need to miss her if you don’t have a heart. No need to miss. But Meg has no family anymore and she has a heart. Common sense. Meg thinks she’s practical and Mr. Roldo is a romantic. “Surely, Mr. Roldo,” Meg says often, “surely you have a heart? ”

“I am wisdom. I am better than jewels. Nothing you want can compare with me,” Markus says, as he follows Mr. Roldo to the water.

There are several children sitting by the water with their mothers. Each child has a pile of rocks in their lap, and they are throwing the rocks into the water and applauding with every tiny splash. “I can do it,” one child shouts. “I did it.”

Meg stands up at the car and watches Mr. Roldo as he clutches his heart and limps toward the water. She watches Markus, bible in hand, looking down at his feet. She watches Noodle tiptoe daintily after the two men, watching them like a hawk, never letting her eyes leave their forms. Noodle’s dead father seems everywhere around her, watching her. Meg sometimes can see his soul hovering, taking care of his child. Meg wants to get back in her convertible and drive off into the sun. She wants to drive quickly and noiselessly away, her hair blowing in the breeze. It’s almost full summer now and she wants to get away fast.

The way these people wallow in their sadness makes Meg tired. Sick and tired. Meg is a trained nurse. She knows they can’t help what they do, but lately she just wants to shake them a little, knock them around, tell them to stop it. “Stop feeling sorry for yourself,” she wants to shout. “Stop it now.” Meg doesn’t know if maybe she wants to say that to herself. Maybe she wants Doctor Mayburn, with his peach-pit gnats, his garlic breath, to raise his hand and slap her. Wake her up. Or kiss her. Maybe she just needs to be kissed. Since her mama died, Meg hasn’t been kissed by anyone.

But Markus turns to her, halfway to the water, and smiles. His teeth are black from the ink. His pallor is grey. And it isn’t what he says to Meg, but more of the way he looks at her that makes her move away from her car and head down to be with him. To be with them.

“Give praise to the Lord,” Markus shouts, “he has heard my cry for help.”

“Be quiet,” Noodle says. “You’re ruining the mood.”

“Oh, my empty heart,” Mr. Roldo whispers, but no one hears him as the children sitting by the water are suddenly noisy and silly. They begin throwing rocks at each other, and their mothers shout and holler.

“Let’s walk further,” Meg says. “Let’s walk a little. Let’s get away from it all.”

The four move on down the beach. They are all wearing variations of white clothing—shirts, shoes, pants, skirts. The asylum outfits are greyish and pinkish, depending on what they’ve been washed with. Meg’s uniform is starched so white it shines in the bright light.

“Lookit,” one of the children says to his friend, as he points at the receding adults. “A bunch of lousy angels.”

His friend throws a rock, but Meg and Markus and Mr. Roldo and Noodle are too far gone for it to hit them.

Meg’s shoulders are high, her walk awkward. She doesn’t know quite where she fits in anymore. It seems as if she’s more in the middle of this group than on the outskirts and, maybe, in this sunshine, walking with this bunch of lousy angels, that suits her just fine. Why should she be in charge? Who, she asks herself again, makes all the decisions in life?

Meg takes hold of Mr. Roldo and tells him, quite plainly, “You know, when I lost my mother last year, I thought for awhile that I didn’t have a heart. I couldn’t hear it beating anymore. I thought it broke. But listen. Put your hand there. Listen with your fingers.”

Mr. Roldo places his hand on Meg’s bulky chest. He smiles with delight.

“When was the last time,” he says, “I got to touch a lady’s breast? ”

“Hear the thump, thump, thump? ”

“No.”

“It’s there. You hear through your fingers.”

“That’s silly,” Noodle says, starting up with her nervous jittery dance. “Mr. Roldo doesn’t have a heart.”

Markus opens the Bible to the first page he hasn’t consumed and starts to rip off small sections and place them on his tongue. “You have changed my sadness into a joyful dance,” he says, his mouth full.

“But, it’s there,” Meg says. “It’s the beating of my heart. My mama left it there within me.”

“I hear nothing,” Mr. Roldo says.

“How else,” Meg says, “could I take care of you? You are my children. How could I love you without a heart? ”

The group stops and turns to Meg. Stares her down. Markus chews slowly, like a cow, manipulating his mouth around the paper.

Meg laughs.

“In the beginning,” says Markus. But then he forgets exactly what he was going to say and Meg says, “Let’s move on. Let’s just keep going.”