Katherine Collins is known throughout her Vancouver neighbourhood of Commercial Drive as the woman who sings. She is the woman who sings on the street, the woman who sings at the Safeway, the woman who sings at the bank. When Collins does speak, it is akin to a performance piece, with flailing arms, a lilting voice, and a beaming face. “I’m the biggest ham in the world,” she said with a laugh, something else she does often and easily.

Collins’s small apartment is modest and homey. Vintage travel posters and California fruit-crate labels hang on the walls, and personal photographs are scattered throughout. Bookcases front much of the wall space in her living room. A few shelves contain novels by the likes of Alice Munro, but most are filled with comics. There are volumes of reprinted newspaper strips like Terry and the Pirates, Prince Valiant, and Krazy Kat, and slipcased hardcovers of vintage Donald Duck. Some shelves are devoted to old New Yorker cartoon albums and books by the magazine’s artists and authors. On the floor, an antique wooden trunk is filled with clipped Sunday comic pages from early-twentieth-century broadsheets. Stacked on and around the trunk are two boxes filled with recent purchases still to be shelved.

When I visited Collins in February, a pile of original art spread out on the dining-room table was the only visible evidence that this sixty-nine-year-old woman with perfect pitch once was the cartoonist Arn Saba, creator of Neil the Horse, a rubber-band-legged character drawn in a style reminiscent of early Disney cartoons and best remembered for a unique fifteen-issue run during the black-and-white-comics boom—and bust—of the nineteen-eighties. Saba spent more than fifteen years combining his love of cartooning with his love of music to produce the adventures of Neil and his friends: Soapy, a feline grifter, and Mam’selle Poupée, a living doll in search of true love. Collins had dusted off the large boards and sheets of film in preparation for a collected Neil the Horse volume Conundrum Press will publish this spring, the first time the character will appear in print in nearly three decades.

Collins did not intend for Neil to vanish along with Saba when, after a life-time of confusion over his gender identity, Saba began transitioning into a woman, at the age of forty-five. When the publisher of Neil the Horse Comics and Stories shuttered in 1989, Saba forged ahead with his plan to transform Neil into a multiplatform brand. He spent tens of thousands of dollars creating a show bible for an animated Saturday morning cartoon, and began shopping a full-colour Neil graphic novel to publishers. A theatre producer in San Francisco who had obtained a copy of Neil the Horse and the Big Banana—a musical comedy that had run on CBC Radio—asked Saba to work up a script and some new songs for a potential stage version of the show. One afternoon, in the fall of 1993, Saba—who had begun his transition but was still presenting as male when conducting business—and his agent met in the producer’s office to receive feedback on the finished product. Earlier that day, Saba’s agent told him the final publisher still in play had passed on the graphic novel, but the possibility of a live Neil musical kept Saba’s spirits up. When the producer arrived, he launched into a lengthy tirade, berating Saba, his script, and his songs, before walking out, leaving Saba and his agent to watch though the office window as he stormed across the parking lot. “That was it,” Collins said. “We had already batted out on the animated show, and now I didn’t have the play. I didn’t have anything.” Saba completed his transition and spent the next year taking on commercial freelance work, none of which was ever used. After that, “I didn’t ever draw another line.”

Arnold Saba, Jr., was born in Vancouver in 1947. His grandfather was a Lebanese immigrant who settled in the city near the turn of the twentieth century and, with his brother, opened a garment business on Granville Street. Saba Brothers was so successful that, by the time it was inherited by Arn’s father, Arnold, Sr., the Sabas were an extremely affluent family. They lived on an acre of property in the city’s Kerrisdale neighbourhood, and their home often was filled with the sounds of swing jazz and show tunes—music that came to mean as much to Arn as comic books.

Saba’s relationship with his father became strained when Arnold arrived home one day and found three-year-old Arn in a Cinderella outfit, playing dress-up with his grandmother. Arnold flew into a rage, and from that point on was convinced his son was a homosexual. When Saba later told his father he was transitioning, Arnold cut him off and refused to speak to him for the rest of his life.

Saba’s mother, Allison, was a cheerful woman who painted and drew cartoons for small magazines. She had a keen interest in newspaper comics and comic books, and introduced Saba to the work of Carl Barks, the Disney artist who created the character Scrooge McDuck and whose stories featuring Donald Duck and his family became a comic-book gold standard among readers and cartoonists. Allison also introduced Arn to the colourful full-page Sunday newspaper adventures of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, which she had clipped and collected in scrapbooks throughout her own youth. When Saba was nine, he began producing a two-year run of weekday strips and Sunday pages of his own Caniff-style adventure comic, to see if he could keep up the rigorous pace.

Saba attended the University of British Columbia on a creative writing scholarship. In his freshman year he created the comic Moralman – a superhero whose “power” was a righteous sense of right and wrong—for the Ubyssey student paper: “The last story I did was about a hippie character who ended up going to the moon, and somehow he met Aiken Drum. I decided the characters were going to sing the song, and that was my first published comic with music in it.”

Saba dropped out of U.B.C., with a stated life plan “to take LSD and draw comics.” He drifted for several years and in the early seventies joined Circus Minimus, a travelling children’s theatre. Saba’s signature role was Professor Smoothie, a braggart in a white velour and satin tuxedo (fabric by Saba Brothers) who would promise to sing the audience the most beautiful song ever written, before spending an uncomfortable length of time scolding his pianist. Professor Smoothie never failed to be booed off the stage before singing a note, much to Saba’s delight.

In 1974, Saba began testing several ideas for a new strip, but had trouble creating characters flexible enough to fit comfortably in a wide variety of situations, as Walt Disney’s characters had for Barks. One day, an idea “hit me like a thought balloon. I had this whole vision and that’s where I thought of Neil the Horse and Soapy and how they would relate to the world and how they would relate to each other and even what they would look like.” Neil was good-natured, childlike, and had a predilection for bananas. His spindly legs and pie-shaped eyes resembled the early Disney style so much that casual readers often told Saba they remembered his character from their own childhood. Soapy was a realistic-looking cat who smoked cigars. He was smart and cynical, but always a loyal and dependable friend to Neil.

As Circus Minimus travelled the province, Saba visited every weekly newspaper in the vicinity, pitching his strip. In September of 1975, Neil the Horse debuted in thirty newspapers. Saba’s early strips resembled the Mickey Mouse adventures drawn by Floyd Gottfredson in the nineteen-thirties, but were more farcical and often set to song. In 1977, Saba moved to Toronto to be closer to the country’s art and media epicentres. He joined a group of local cartoonists syndicating their own strips to Canadian weeklies under the name Great Lakes Publishing. This second version of Neil was a nonsensical gag strip that Saba often said was more symbolic of a comic rather than actually being one, but was crucial for the addition of Mam’selle Poupée, a jointed doll with large breasts and a small waist who spoke in a broken French accent. Poupée was smarter than Neil and more scrupulous than Soapy. Her romantic nature let Saba indulge in more heartfelt storylines, and her desire to “make it” in show business allowed him to bring his own love of song and dance to the forefront.

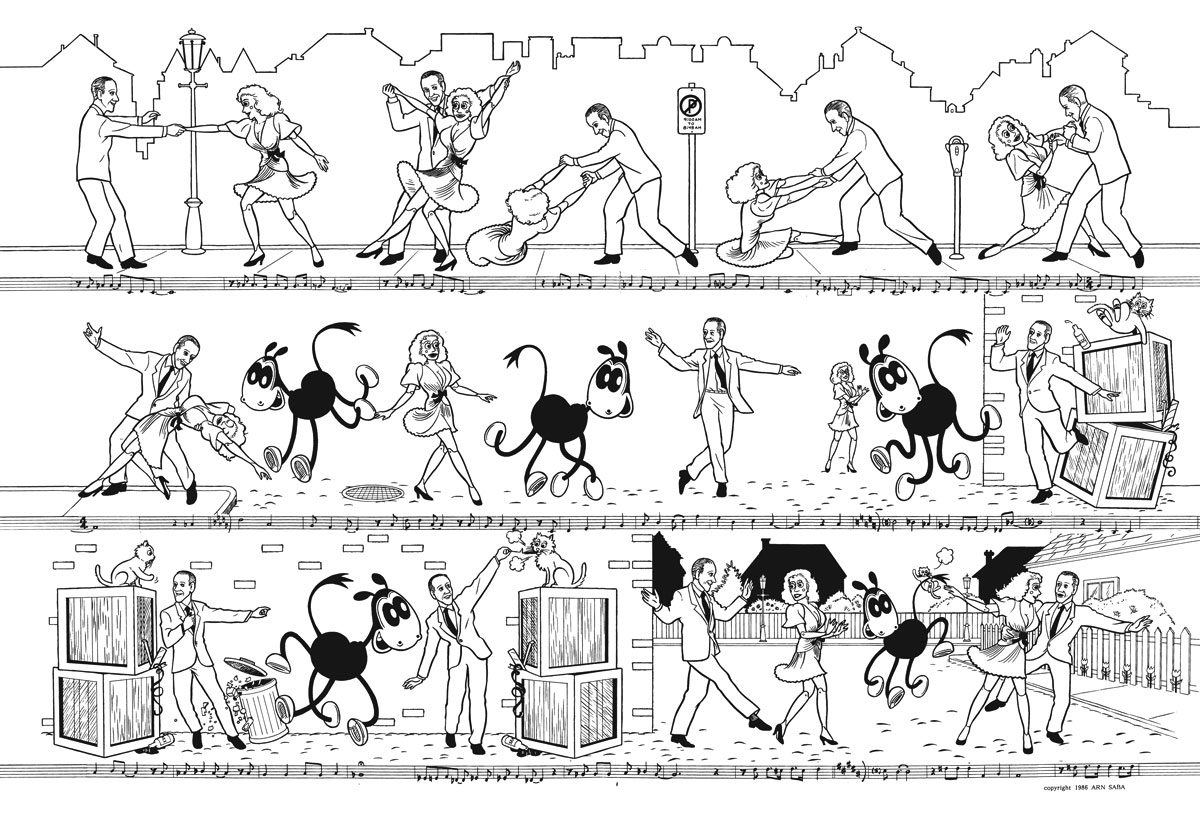

Song and dance were integral to Neil stories. This was especially evident in Saba’s two-issue tribute to Fred Astaire

Saba frequently contributed lighthearted reports to CBC Radio while living in Vancouver. When he arrived in Toronto, he became a regular contributor to Morningside, the network’s weekday morning program. Saba and host Don Harron, who was also a comics lover, had an instant chemistry. Together they discussed Saba’s favourite artists and performed skits based on old newspaper strips. In 1982, Morningside found itself with a year-end budget surplus. Saba offered to spend it, and quickly wrote a script and five original songs for a musical comedy. Neil the Horse and the Big Banana saw Neil, Soapy, and Poupée travel to South America in search of a jewel-encrusted banana. Once again Saba’s story had its Disney influences, this time Barks’s treasure-hunting plots starring Donald Duck and his nephews, with Saba’s characters taking time out from their adventure to sing. The five-part program was a critical success. Saba hoped to produce more radio plays, but his CBC career soon ended when internal restructuring made it more difficult for freelancers to get airtime. Saba also felt less welcome at Morningside after Harron departed and was replaced by Peter Gzowski, who did not share Harron’s love of comics—or of Saba.

Black-and-white independent comic books began to grow in popularity in the late seventies and early eighties, as titles like Wendy and Richard Pini’s Elfquest, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Dave Sim’s Cerebus found a welcoming audience though the burgeoning direct comic-shop market. Sim, based in Kitchener, Ontario, was a fan of Neil the Horse. “It was a very odd strip,” Sim told me recently. “It was definitely far more in the charming category than the funny category, though it had its moments there, too.” When Sim and Deni Loubert, his then wife and business partner, decided to expand their press, Aardvark-Vanaheim, beyond publishing Cerebus, they contacted Saba, and in 1983 the first issue of Neil the Horse Comics and Stories appeared on stands.

Sim and Loubert’s mandate was complete creative control for their artists. “We had a huge discussion about what he wanted to do,” said Loubert, who remains close friends with Collins today. “We’d never really done something like this. Cerebus kind of grew organically. So we talked at length.” Saba settled on a format reminiscent of the Rupert Bear children’s annuals he had loved. Every issue of Neil the Horse was a grab bag of newspaper strip reprints, lightly illustrated prose pieces, a letters page answered by Saba in character, and paper dolls with accompanying outfits for Poupée, drawn by Barb Rausch, who had been a popular “reader-contributor” of fashion designs to Katy Keene, Bill Woggon’s teen-model series published by Archie Comics in the nineteen-fifties and sixties. Rausch and Dave Roman, an artist and jack-of-all-trades, assisted Saba with much of the plotting and pencilling work, allowing him to follow Walt Disney’s model of stepping back to oversee others as they worked on his creations.

Saba did not set out to make comic books, but they were the format that allowed him to perfect his creation. Neil, Soapy, and Poupée’s new adventures were non-linear and surreal. Many took place in their home base of Bananaburg, but the characters also could find themselves sailing to New France with no explanation, and none needed. The more grounded Neil stories featured settings that seemed timeless, with only occasional present-day flourishes: in one story, Poupée wears Olivia Newton-John–style workout gear; in another, Neil breakdances with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

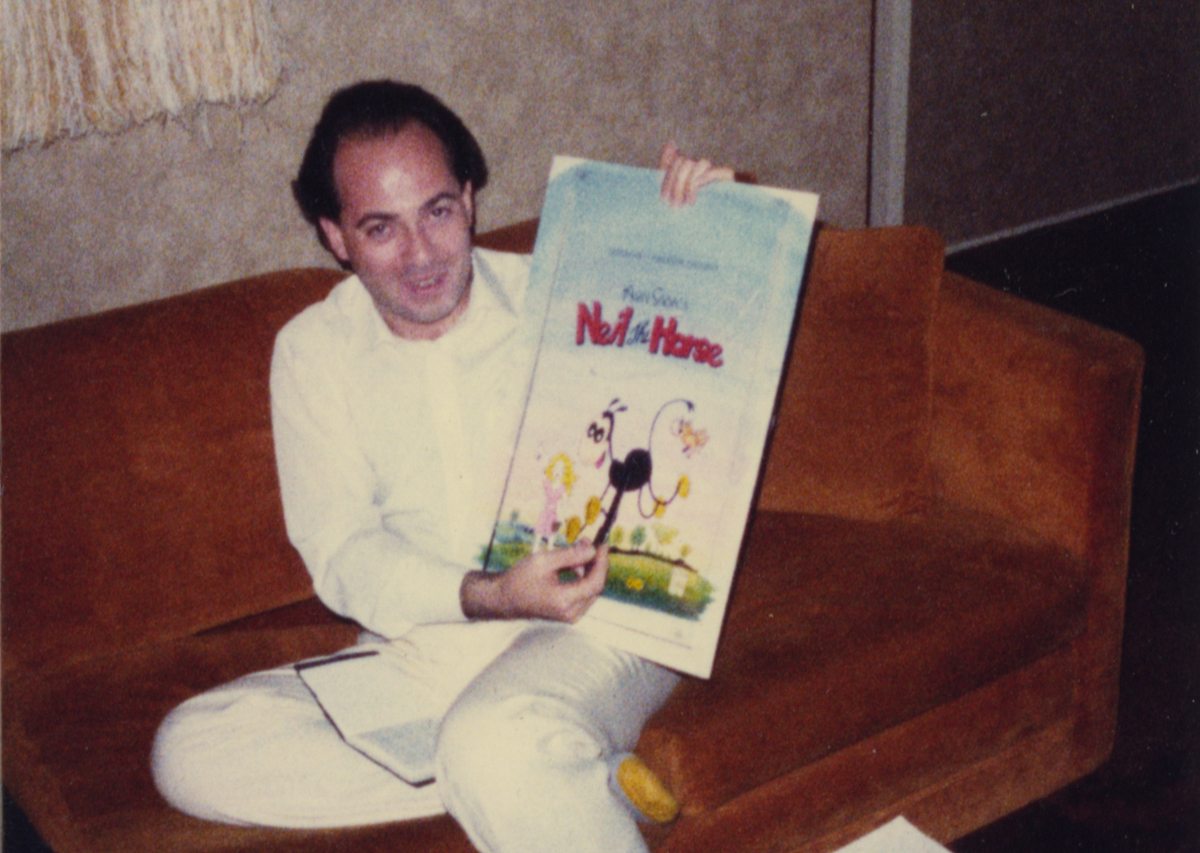

Arn Saba, holding the original cover art for Neil the Horse Comics and Stories No. 1, circa 1982 (Courtesy of Dave Sim)

Characters in the Neil comic—which often featured the tagline “Making the World Safe for Musical Comedy”—broke out into song and dance even more frequently than they had in Saba’s newspaper strip. The book’s most uncommon feature was the sheet music for original songs Saba wrote as a soundtrack to the new Neil stories in each issue. A two-issue tribute to Fred Astaire featured not only several new songs, but extensive dance numbers between the Hollywood icon and Poupée, which Saba slavishly choreographed by printing out stills of Astaire in motion on a thermal printer attached to his VCR.

Sim and Loubert’s personal relationship ended in 1983, and Aardvark-Vanaheim’s assets eventually were split between them. Sim retained Cerebus and Loubert took all the remaining titles, including Neil, and formed a new company, Regenade Press. Neil’s numbers were strong—between six thousand and ten thousand copies per issue, according to Loubert—but by the end of the decade, the black-and-white market was suffering from rampant speculation, and Renegade folded in 1989. The final issue of Neil the Horse debuted the animation-friendly characterizations Saba had been working on. Neil remained largely unchanged. Soapy gained fingers and the ability to walk upright, while Mam’selle lost some of her over-the-top sex appeal. Several production companies, including Toronto’s Nelvana, optioned the animated Neil over the next several years, but ultimately all passed on turning it into a series. After Saba’s ill-fated meeting in San Francisco, all avenues were exhausted, and Neil was never seen again.

Arn Saba felt uncomfortable in his body for as long as he could remember. When he was about six he told his mother “that I wished that I was a girl instead of a boy. My mother, of course, had no idea what to say.” Saba avoided traditional male activities in school, such as sports, which made him a target to other male students who “could tell I wasn’t regular.” As an adult, Saba’s confusion made him unsure how to act or feel in his relationships with women, none of which lasted for a significant length of time. While living briefly in London in the late eighties, Saba sought out the local transgender community and finally realized he was a lesbian woman in a man’s body. He explored many options and, after moving to San Francisco, began a three-year transition process. “Katherine started budding out and I realized how much of a different person she and Arn were,” Collins said. “To my great surprise, she was not initially an adult. I had turned into a little girl inside. That really gave me insight into who I was going to become, because I had to grow up through the confusions and the aspirations of being a little girl.” Collins said it wasn’t until after her transition that she realized how much Neil, Soapy, and Poupée were a subconscious projection of her own personality: “One of them is the child that I’ve retained in myself. Then there’s the bad-tempered, cynical, businesslike one. Poupée was representing my desire for a partner, which was never possible for dear old Arn Saba. She was my female self.”

In 1994, Collins met Bobbie Bentley, a former doctor whose career had ended after a debilitating car accident. “She was exactly what I was looking for in every way and she felt the same about me,” Collins said. “I had never before had what I’d call a successful relationship in my life. I was an incomplete person. If you don’t really understand who you are and you don’t know what other people want from you, you can’t really give love. I had learned finally how to give love.” Collins and Bentley lived happily until 1999, when Bentley was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and died six months later.

Collins stayed out of the public light after her transition, until 2003, when the San Francisco Examiner ran an item reporting, “When narcotics cops raided a Russian Hill apartment Tuesday night, they did more than confiscate the largest stash of magic mushrooms this city has seen in twenty years. They answered a question some underground comics buffs had been asking for years: What on earth happened to Arn Saba?” (Collins preferred not to go on the record with me about her business activities, but insisted the confiscated mushrooms were not hers.) She received a small fine, but under post-9/11 restrictions all state and municipal felony convictions were being forwarded to national security. Collins had her green card confiscated and was given a trial date. On the day her hearing was to take place, Collins opted to leave the country and return to Vancouver rather than risk jail time.

A small Neil the Horse renaissance has been slowly building since 2013, when Collins was inducted into the Joe Shuster Awards’ Canadian Comic Book Creator Hall of Fame. That same year, Hermes Press contacted Collins about releasing a collection of Neil comics, but the publisher’s plan to crowdfund the book floundered. Andy Brown at Conundrum eventually picked up the project, and will release The Collected Neil the Horse in May, when Collins also will be inducted into the Doug Wright Awards’ Giants of the North cartoonist hall of fame.

As we talked, Collins frequently referred to having been “fired” from the comics community in the nineties. She believes her transition was a factor—she was later told that the San Francisco producer who scolded her had discovered she was transiting and acted as he saw fit—but admits she has no way of knowing for sure. I asked her how she felt about a potential comeback now, at a time when a transitioned Olympic athlete can appear on the cover of Vanity Fair in a corset. “It’s amazing to think how much has changed in the past twenty-five years,” she said. “Of course I feel good about it—I’m very, very pleased. But for an older person like myself, it’s sort of irrelevant. Younger people, forty and under—they completely get it. A trans person of a younger age can do anything they want anywhere they wish. But it’s not true in my life. I don’t have a partner because lesbian women my age bought the party line of the feminist revolution of the nineteen-seventies that male-to-female transexuals were crazy, destructive, and evil. . . . It’s really dreadful.”

When Collins and I first started corresponding in 2014, she said the Shuster induction had given her back a degree of the confidence she lost after her career ended. She had recently purchased a Wacom digital tablet, and said she planned to begin drawing again. When I visited in February, she was further lifted by the chance to connect with a new generation through the Doug Wright honour, and by Conundrum’s offer to publish the long-unseen Neil graphic novel. I asked her if she still had not drawn since the early nineties. She said she hadn’t. Collins was diagnosed with leukemia shortly after returning to Vancouver. She is considered cured today, but still suffers from diabetes and a number of undiagnosed health problems that have left her with mobility issues and chronic fatigue that prevent her from drawing. “It’s ironic to have lost my career and to have gone through all those years thinking it was never going to come back, that I was a failure, that no one would remember me, and then suddenly—hey it’s back!” she said. “But I’m not well enough to do much. So it makes me feel bitter, to be honest. I’m really excited about the possibility of doing new work. I’m sorry if I die or live a miserable existence and can’t do it, but I want people to know I’m going to try.”

(Originally published in the May, 2017, issue of Quill and Quire.)