John Brook in his Avenue Road office, circa 1963.

Had you walked out onto Bloor Street on a spring evening in 1960 and turned north up Avenue Road, you would have seen, next to the old Park Plaza Hotel, built solidly of brick, the hostelry’s new wing, standing there in juxtaposition. It was spare, glassy, shimmering—a tower that looked as modern as the Avro Arrow jet fighter.

The street lamps switch on. You glance up from the sidewalk, seeing their incandescence against a thicket of hydro wires—a stringy mess of the type that appalled the sophisticated Peter Dickinson, the young architect who designed the Park Plaza addition. A few years earlier, Dickinson, on arriving with his wife, Vera, from England, had declared Toronto the ugliest city he’d ever seen. With such modernist efforts as the Park Plaza addition, he had done something about it.

But at dusk, on this mid-twentieth-century night, the contrast between spanking new and weary old only emphasizes the problem—for the hotel addition sits amid crummy urban flotsam. A few yards up the street, garish strings of bare light bulbs illuminate the chrome-encrusted, obsolescing Buicks, Chryslers, and Oldsmobiles in the used-car lot of British & American Motors. Across Avenue Road, at Yorkville Avenue, the Supertest gas station adds to the clutter, its washable, white-enamelled exterior plastered with versions of the company’s circular crest, a red maple leaf underlined by the claim “ALL CANADIAN.”

But something else across the street catches your eye.

With darkness deepening and artificial light editing the midtown cityscape, what you see is a squared-off, spare slice of something like the new Park Plaza, grafted onto old Toronto—a modern, glass storefront added to an old three-storey Victorian house.

The sign over the huge show window says “J & J BROOK LIMITED.”

What’s in the window grabs you: a couple of chairs under a spotlight. They are not the monstrous recliners you see perpetually on sale down at Lyon’s at Yonge and College; these chairs bear no resemblance to the chesterfield suites upholstered in flower-patterned chintz fabric that Consumers Furniture sells at “warehouse prices” out of its big showroom at Bloor Street and Dovercourt Road. They are extraordinary chairs, as scant and simple as one of Dickinson’s buildings. Their structure is slim—just bones really, merely there to hold up their throw cushions.

A recent headline from the newspaper flashes back as you stand there on Avenue Road under the street light. “ARE YOU ‘MODERN,’ OR ‘BORAX’? ” it had read. With this recollection, everything clicks—this is that “modern” furniture everyone is talking about. “‘Borax’… is the huge, bulky, overstuffed variety [of furniture] that plugs up many a small-scaled home in Canada today,” the actual news story had reported. “Yes, ‘borax’ is disappearing… Instead furniture makers are streamlining their products… riding the tail of the Scandinavian rocket currently sweeping around the world.”

“J & J Brook Ltd. opened their doors in January 1952 and at the time was one of the only, if not the only firm doing contemporary interior design in Canada,” Canadian Interiors would reflect in 1965. When John Brook, who was born in Salmon Arm, British Columbia, in 1914, came of age in the nineteen-thirties, industrial design was so nascent in this country that there was not yet a program in the field offered at a Canadian university. Though Brook’s inclinations might have been to become a Canadian Raymond Loewy or Henry Dreyfuss—U.S. industrial designers of the nineteen-thirties whose names became household words—he pragmatically majored in chemical engineering, earning his degree at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. But he was not a pragmatic man, he was an idealist; those he came to admire included Noam Chomsky, Maude Barlow, Mel Hurtig, Mel Watkins, and journalist Linda McQuaig. Like Toronto architect Wilfred Shulman, he was a feisty N.D.P. supporter.

Brook met his future wife and partner, Joanne Price, in Niagara-on-the-Lake, where her family summered and she attended school part of the year. “I saw him at the first day of school, in flannels and a blazer, and I decided that was for me,” Joanne said. The Price family’s ancestors were Welsh, but Joanne, who was born in Cleveland in 1917, also had German blood on her mother’s side. Her outlook was distinctly Canadian, the result of years of her time spent in Niagara-on-the-Lake, which, she recalls, had less pretence than now; it was “a little Irish town, dropped in the middle of nothing.” She spent her youth in a state of flux, desperate not to return to Cleveland, and, casting about, found and took a design course in Toronto, “learning to make patterns for clothing. I tried very hard to get a job in that [garment] district on Spadina Avenue. I climbed up and down the street.”

Completing her studies, she returned to Niagara-on-the-Lake. One day, in 1936, as the clock ran down (“I had twenty-four hours to get a job in Toronto or I’d have to go back to Cleveland”), Joanne bought a day-trip bus ticket and returned to her Oz. “I went to a lovely little [clothing] shop” on Avenue Road near the Park Plaza, Joanne remembered. It was directly across the street from the future location of J. & J. Brook. She got a job doing alterations. The next summer she sold woollens (New Brunswick hand-woven skirts and sweaters) at that store and in Niagara, and learned that “I could sell anything, apparently.” Perish the thought, thought Joanne Price—but this was not an unhandy skill in 1936, 1960, or 2001.

Some years before, a fellow Cleve-lander, Philip Johnson—who The Conran Directory of Design called a “socialite who became an architect and a creator of styles”—had put on his famous exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, introducing the purity of European Modernism to North America. Joanne, married by 1940 to John Brook, remembers nothing of it; that their taste was, if anything, Elizabethan—fussy and florid. But modern ideas would simmer everywhere during the war years, which the Brooks spent in Nobel, Ontario, near Parry Sound. John worked in the explosives factory there, and Joanne did the midnight shift in the plant hospital office.

After the Second World War, it was through John’s brother Philip—an architecture student at the University of Toronto, where such luminaries as professor Eric Arthur taught the new Bauhaus principles—that modern design ideas filtered into John and Joanne Brook’s consciousness.

Returning to Toronto, Philip lived for a time with the Brooks and his “contemporary architecture” came with him. John worked at Dow Chemical, establishing their national sales organization. After their second child was born, he was convinced his wife would go crazy staying home. “What about a loom? ” Joanne remembers him asking. “I said, ‘That would be stupid. You’re still just looming away, all by yourself.’ ‘What about screen printing? ’ And I didn’t know what that was.”

Few people outside design circles did, but silkscreening and block printing, both on paper and textile, were to modern graphics what oil paint and brush were to baroque canvas: a simple technique that produced instant results.

“So he started making screens and doing little squares. He did a design for a drapery fabric. We made all the curtains for the house.” It was a bit like a yachtsman giving his wife a spinnaker: who was this really for? “One afternoon… Joanne Brook came home from a Niagara-on-the-Lake hospital with her new baby son, glanced downstairs and recoiled at the sight of a 30-foot table monopolizing her 30-foot basement,” Canadian Homes & Gardens reported. “Joanne, an irrepressible brunette, passed the baby over to her husband John, propped her hands on her hips and inquired tartly, ‘What are we going to do here—throw banquets? ’” But “we were transplanted,” said Joanne, “if this is what was going to happen—contemporary fabrics, not big floral English stuff.

“There was this viscous stuff, like custard,” she remembered. “You’d pour it onto the screening table and, with a piece of wood, push it across. The goopy ink went through the screens where the pattern didn’t block it out. For colour, you passed the fabric under several complementing screens that together created the whole.”

Philip exhibited some J. & J. Brook fabrics with students’ project designs at the University of Toronto, and soon Joanne Brook was making the rounds of the Toronto architectural offices, including Page & Steele, where Peter Dickinson first made a splash. Later, with his own office, “He sometimes failed to pay his bills promptly,” Joanne said. “Colin Vaughan ran the office and he said to me, ‘You know Peter.’”

In 1947, a friend of the Brooks, architect Bill Grierson, was scouting around for examples of good modern design for an exhibit at the University of Toronto’s school of architecture, and picked some J. & J. Brook fabrics. Students liked what they saw, and soon Grierson was bringing a stream of young architects to the Brooks’ home. The first big order, for fifty-five yards, came in from the head of the contract division of Eaton’s College Street for a pattern called Flight. It was specified on a job at Malton Airport (now Pearson International). John Brook had worked the pattern out in his spare time. “They looked like geese in flight, but they could also be clouds, or something flying,” Joanne remembered. With Flight, the Brooks’ fledgling modern-design enterprise took off. In May of 1954, it was reported that “from a basement, they’ve graduated to a smart third-storey shop on Toronto’s Avenue Road, tastefully furnished and temptingly draped with their upholstery and drapery fabrics. Seven years ago their taste was dyed-in-the-wool Elizabethan. Today they create only the most positive contemporary designs… to the uninitiated, some of those designs resemble the doodle you make on the wall of a phone booth. But even the confirmed critics of contemporary admit that they find the Brook creations pleasing, graceful, even entertaining.”

Joanne Brook demonstrates screen printing at Simpson’s Homemakers’ Show in 1951.

Looking through the plate glass of the J. & J. Brook store in 1960, you see, further back and up a few steps, modern art on the nubbly, exposed-brick walls. A photograph shows a boomerang-shaped ceramic sculpture hanging on the wall, perhaps for sale; there were often paintings—on this day perhaps on loan from nearby art dealer Av Isaacs—sometimes there were wall hangings by Karen Bulow, a Montreal weaver, one of the era’s stars of Canadian textile design.

Interest in the line of fabrics had trickled down to the broader public. “‘Tobacco Leaf’ is much in favour,” reported Canadian Homes and Gardens in a mention of one of John Brook’s patterns, created, apparently, before the era of political correctness over smoking. “It is lovely in sandalwood with chocolate brown vein on natural, or blue grey with a bright citron vein. Designers Mr. and Mrs. John Brook have it in mushroom and black on white in their living room.” A design scholar would one day comment, “Tobacco Leaf has a bold and free-spirited style that is characteristic of the work of the husband-and-wife team operating as J & J Brook, whose draperies were admired for inventive design.” By one account, Tobacco Leaf resulted when John “slapped a slice of wet rye bread on paper, admired the textured effect and turned it into a design.”

“John is the designing genius of the team,” the readers of Canadian Homes & Gardens were told in 1954. “He’s a dark scholarly-looking man of 39 with a subtle sense of humour, just a trace of British accent acquired from ten years spent in England, and a talent for gleaning ideas from the most unlikely sources….John feels that anyone, after sufficient contact with design, will develop an interest in good contemporary. You won’t acquire it overnight and you can’t learn it in school, he warns. But he believes its fresh creative forms—some of them, at least—will appeal to every person, depending on your inherent likes and dislikes.”

The Brook designs caught the attention of the National Industrial Design Committee (later Council), a body set up in 1948 by the federal government to promote Canadian industry through better design. It operated under the auspices of the National Gallery of Canada, staging exhibits and opening permanent design centres as public showcases in several cities (in the nineteen-sixties, one would be installed in the chic new Colonnade Building on Bloor Street). The council also published an annual design index of products judged to be outstanding.

John Brook’s Manx—inspired by the coat of arms of the Isle of Man—Rush and Reed, Graphic, and Scrub Oak were early award-winners in the period. In 1956 alone, six fabric designs created for J. & J. Brook by Micheline Knaff won prizes and were listed in the design index: Blockweave, Highlights, Elipse, Fiddlesticks, Weave, and Foliation. Those names aptly captured the simplicity of their rhythmically repeating, silkscreened, or woodblocked graphics. Others by John Brook included Galaxy, Squiggle, and the clever Thur-ber, which resembled the doodle-drawings by the famous cartoonist James Thurber.

“Yes, an engineer, designing fabrics,” said Joanne. “That was post-war Modernism.” John Brook quit Dow and put his chemical expertise into ink and textile production and, soon enough, industrial design itself.

Indeed, there was soon more going on at 33 Avenue Road than modern textiles. About those chairs in the window: in the nineteen-fifties, J. & J. Brook had added some famous lines of furniture—designs by Denmark’s Hans Wegner, for instance, and Paul McCobb of the U.S. Joanne recalled that it wasn’t much of a leap for John to start designing pieces himself. “We saw what people were doing with our draperies. We didn’t, either one of us, have an interior design background, but we thought we could do as well.” It wasn’t unusual for the time. “Designers took on a myriad of roles. They crossed disciplines like design, engineering, production, and even marketing, engaging in unprecedented collaborations.”

There exists a photograph, taken in 1999, of Rhea Shulman, wife of Wilfred Shulman, a University of Toronto–educated architect who designed apartment houses, sitting in her dining room on a three-legged Hans Wegner chair like the ones J. & J. Brook sold. She is next to a blond wood dining-room sideboard without legs that hangs from the wall—an original J. & J. Brook piece. In the picture, her hands are blurred as she talks animatedly.

During the nineteen-fifties and sixties, Rhea Shulman sometimes stood on the sidewalk in front of J. & J. Brook just to see what was new. Her husband’s office was in the modern building he had designed up the street at No. 99. She could walk a few steps from there, or from Bloor Street, with its clattering pre-war streetcars and stuffy traditional shops, to find in this storefront the sharpness, the newness, the optimism that radiated from post-war design.

The Hans Wegner chairs that J. & J. Brook sold were called “completely faultless” by Danish designer Paol Henningsen. Paul McCobb was Joanne Brook’s own personal favourite. Said Rhea Shulman about J. & J. Brook: “They were, to our mind, the foremost designers and makers of modern furniture—a wonderful, wonderful design company.”

By the mid-nineteen-fifties, much of the silkscreening was farmed out to Jimmy Farquahar, a screen-printer on Front Street. The later furniture was usually made in Toronto, too. In the early nineteen-sixties, contracts from J. & J. Brook “sort of set me up in the business,” remembered Gary Sonnenberg, owner of Craftwood Products, which manufactures for Herman Miller, among others, in 2001. He used to park his sunroof-equipped Volkswagen under the shade of a big tree in the gravel parking lot behind 33 Avenue Road.

Piece by piece, then, the Shulmans furnished their James Murray–designed, radiant-heated home in Moore Park, north of downtown, with Canadian modern furniture, much of it from J. & J. Brook. “All those young architects bought houses in that area that Jim designed for medium-priced, middle-class people,” Joanne said.

As for that show window on Avenue Road, well, “It was a terrific window, marvellous window,” said Joanne. “People used to get stuck in traffic, so there they would be, looking in. I kept making curtains for all those architects, which they wanted for their modern houses. Everybody was helping everybody else get this modern fling.”

By 1960, J. & J. Brook, if it had been Toronto’s pioneer in modern, was no longer the only game in town. Continuing north on Avenue Road, the modern shopper would have seen Herman Miller’s own showroom, just south of Davenport Road; its display window—like J. & J. Brook’s, tacked to an old Toronto Victorian—stocked with Charles Eames’s new sculptural office furniture known as the Aluminum Group.

Herman Miller was based in Michigan, the world capital of borax by virtue of thick, hardwood forests that were turned into lumber, then, typically, frames for recliners and overstuffed couches. The company had deep roots there, but its products and policies evolved into the antithesis of over-stuffed—there wasn’t a ball of cotton batten attached to the fibreglass Eames shell chairs that would become twentieth-century icons. In the town of Zeeland, where Herman Miller was based, wood was not bolted into frames—it was defiantly moulded into sensuous, elastic-looking office screens, chairs, and cabinet doors.

Meanwhile, mere steps away from Avenue Road, in the pre-Bohemian, pre-chic Yorkville of 1960, Shelagh Stene was bringing in ever-sleeker teak from Scandinavia, and, in 1957, on Bloor Street, Georg Jensen, patriarch of Scandinavian modern and its more costly accessories, so thoroughly gutted and modernized his nineteenth-century shopfront to facilitate sales of silver and ceramics that, as late as the nineteen-eighties, architecture critic Patricia McHugh said it still looked good.

Readers of Canadian Homes & Gardens would have also known, from regular advertising, that the great American firm Knoll was purveying wiry Bertoia chairs and memorable credenzas from a shop uptown at Yonge and Eglinton (“WANT TO COME UP AND SEE MY FLORENCE KNOLL?” a Globe & Mail headline asked over an admiring story about them in 1998).

And, while the furniture department at the flagship Simpson’s store on Queen Street might have seemed, to some, a likely borax desert, the fact was that for some time the masses had been invited, via newspaper and magazine ads, to check out Ruspan—“IT’S NEW… IT’S RIGHT”—the informal, even cartoonish furniture lines (splayed legs made pieces look apt to up and walk away) designed by Toronto’s Russell Spanner. It was listed on the National Industrial Design Council’s design index and manufactured at a plant on Elm Street in Toronto (the building later became part of the World’s Biggest Bookstore). Ruspan became one of Simpson’s most popular lines.

From its contract division, Simpson’s sold other Canadian modern lines, such as desks designed by Dutch-born Jan Kuypers, and the chairs of Donald Strindley, first head of the National Industrial Design Council, both made by the Imperial Furniture company of Stratford, Ontario. Spanner notwithstanding, the truth was that airports, banks, museums, and office towers were the real market for modern furniture. At work, “durability and suitability were often ranked higher than cost,” and, in new showcase buildings, fussy Chippendale chairs seemed out of place—at least at the mid-point of the twentieth century.

Office buildings had complex needs, and interior designer Alison Hymas remembered specifying furniture from Knoll or Herman Miller for general purposes, “then I would design things that had to accommodate a special purpose.” By the mid-nineteen-fifties, J. & J. Brook was doing the same thing, and even had a staff of its own designers, including Tony Wolfenden from Britain. Hymas remembered them as formidable competition, “a major force, progressive and aggressive.”

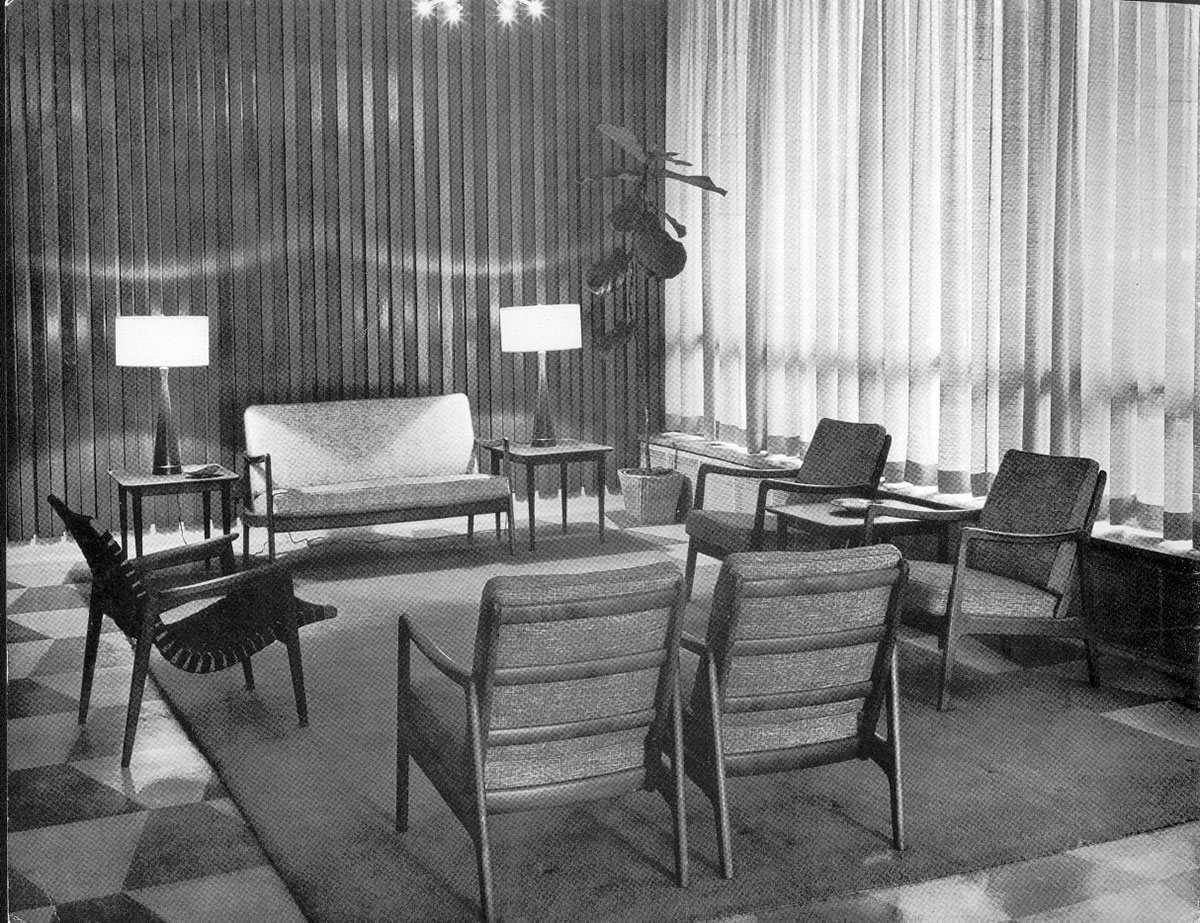

A 1959 view of J. & J. Brook’s showroom and office at 33 Avenue Road.

The Brooks’ Canadian interpretation of modern was straighter, squarer than the slim, sculptural, Swedish-modern teak of the Scandinavians. Canadian potter Mayta Markson thought it reflected typical “Canadian reserve,” and liked it, though remembered Joanne Brook herself as a vivacious, “elegant, very beautiful woman.” Canadian modern in general, and certainly the work of J. & J. Brook, was, for the most part, woodier, blonder, more informal than what American firms like Knoll (big on steel, leather, even marble) and Herman Miller (fibreglass, moulded plywood) were doing.

John Brook looked less severe than modern master Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in a thumbnail picture published with images of his Modulator office grouping, a series in oiled walnut and brushed aluminum available with a matching $29.50 (not cheap in those days) wastebasket. He is wearing large, light, fashionable glasses, with wavy hair and a dimpled chin.

Yet J. & J. Brook ’s office furniture may now be judged to be as squared and chiselled and metallic as van der Rohe’s. J. & J. Brook ’s mid-nineteen-sixties Interchange series—chairs, coffee tables, and an unusual hybrid of the two, combining two seats and a seat-level table—were built around slim, squared, chromed-metal frames. Pictures of the series, on file at the Toronto Design Exchange, show everything connected at right angles, except for the seat cushions, which were flat planes, tilted just so for comfort and dramatic effect.

A catalogue of the early nineteen-sixties showed an extensive and sleek line of office-oriented furniture and accessories in the same spirit. They included various stacking chairs, the Graphic armchair, and a range of sculptural secretarial chairs. “Our biggest problem isn’t pushing Canadian designs on executives,” John Brook was quoted saying in the Toronto Star’s Star Weekly weekend magazine in March, 1962. “It’s convincing them that their secretaries and wives aren’t authorities on office interiors. They bring a residential taste to the office; they over-extend the nesting instinct. They like things too cozy.”

The Interchange line’s minimalism carried over into advertising. A 1966 ad in Canadian Interiors, part of a series, contained no descriptive text, just an image of the furniture, the words “DESIGNED BY J & J BROOK,” and the name Contemporary Distribution, owned by J. & J. Brook.

The Brook’s flagship product of the nineteen-sixties was the Tuxedo series—a rich, leathery, Miesian sofa chair group used in offices and homes.

George Baird, an up-and-coming young architect (later a professor at Harvard) bought one in 1963; a Toronto Life writer who saw it in his Annex home in 2001 commented, “its mid-century modern looks sit easily with two nearby Le Corbusier armchairs.”

Joanne, who managed the large custom projects, such as the Union Carbide Building on uptown Eglinton Avenue around 1958, held fast to the tenets of Modernism—that, for instance, environments be fully designed, not mere containers into which anything at all was placed. “We feel very deeply that it is essential that the interior be a continuation of the architectural creative concept,” she told Canadian Interiors in 1965. “More often than not we find the standard solutions unacceptable… We feel it necessary to interpret the client’s physical and psychological needs in new creative ways, not making him uncomfortable but taking him much further than he would think he dared go.”

Sometimes further.

For Union Carbide, “We commissioned a stainless-steel sculpture from an artist in upper New York state,” Joanne remembered. Shaped like a Christmas tree, it was too much for the company’s vice-president, who wouldn’t allow it to be installed. (It was later installed in another J. & J. Brook project, the University of Waterloo’s library in Waterloo, Ontario.)

Other clients of the Brooks included Canadian Kodak, Woodbine and Greenwood racetracks, and the Bank of Nova Scotia.

A celebrated event of the modern era was the Toronto City Hall competition—first, the worldwide contest to find an architect, but, later, as the building neared completion in 1964, the proposal-call to furnish its interior spaces and offices.

J. & J. Brook, through a partnership with manufacturer Sunar and Mitchell Houghton, was among the finalists, as were the contract divisions of Eaton’s and Simpson’s. The details of their proposals were dutifully laid out in the July, 1965, issue of Canadian Interiors; the Brook proposal played down flamboyancy—“the architecture had to be the prime visual statement,” Joanne would write. Among the many ideas the Brooks offered up was a light, portable, moulded plywood shell chair with a sleigh-type runner base—the better to ease aldermen in and out of informal debate in the lounge of new City Hall’s flying saucer–like main chamber.

But the contract went to Knoll, despite its proposal being well over budget. “Just what is Knoll? ” Star staff writer Frank Moritsugu asked, as the controversy bubbled in the spring of 1965. “Knoll is Rolls,” as in Royce, he learned. Decades later, noses all over the Canadian furniture industry were still out of joint. “You can do a terrific job at a million dollars more,” said Joanne. Yet, the Knoll pieces were mostly manufactured in Canada, prompting the authors of Design in Canada, a landmark history published in 2001, to write, “the implication was that Canadian companies were good enough to manufacture the furniture but not good enough to design it.” University of Toronto architecture professor Virginia Wright has called the furnishing of Toronto’s new City Hall “the country’s first, and to date only, public furniture scandal.” Mayor Phil Givens’s best answer at the time—not a bad one really—was simply, “Why, I find it [Knoll’s plan] beautiful… this is very hard to do. It would be like explaining love to you… It sends me… it grabs me… I mean it moves me.”

The Brook-decorated lobby of Wilfred Shulman’s 206 St. George Street, circa 1954.

In the late nineteen-fifties, J. & J. Brook opened an office in Montreal, where Joanne had often bought art for the Toronto business and where, among other jobs, the company won contracts to decorate offices at I. M. Pei–designed Place Ville-Marie, Montreal’s flagship office complex. She remembered the Canadian Handicrafts Guild on Peel Street, not far from Place Ville-Marie, where “Eskimo art” (“That was what we called it at the time”) was sold. Though vernacular, it was cool, curvy and went beautifully with modern furniture.

And it was in Montreal, at Expo 67, held past the mid-point of the century that had been promised to Canada, that modern furniture would find its full expression, its high point, Joanne remembered. “Everybody I know from the design world in Toronto was down at Expo,” she said. “Some of them did the best work they ever did.”

That year, the Star Weekly—about as mainstream as media could get in Canada—published several articles on modern furniture at Expo, and a very mod double-page spread showing youthful men and women in tights dancing, phoning, spinning LPs, and exercising around knock-down furniture designed by Canadian Norman Strauss. Elsewhere, another lengthy spread was published on the designers of furniture used in various pavilions and displayed in model suites at Habitat, the Expo exhibit/housing project designed by Moshe Safdie, a McGill University architecture student. The likes of Alison Hymas, Jerry Adam-son, Jacques Guillon, Sigrun Bulow-Hube, Hugh Spencer, Macy DuBois, Keith Muller, Michael Stewart, and Christen Sorensen were suddenly, if briefly, famous.

In the Expo afterglow, the public’s sensibilities seemed transformed.

In 1959, the Star’s Gordon McCaffrey, a youthful reporter with an interest in design and Hans Wegner chairs in his home, had lamented in a story that “what Canadians apparently like is the garish, the glittering, and the gaudy.”47

This was not apparently the case in 1967. “In the verdant corner of western Ontario around Kitchener, Waterloo and Stratford, you can find towns with whole neighborhoods dominated by brooding, red brick hulks, grimy from a hundred years or more of stubborn, four-square survival,” James Purdie wrote in his Star Weekly home-design column, taking stock on events. “These are Ontario’s original furniture factories. In some of them, sons and grandsons are still looking through catalogues of their fathers for design ideas, while works foremen take a leg from any table, an arm from any chair, and put them together for next season’s ‘trend’—a trend which, we can now hope, will never come to pass.”

“One of the most important achievements of Expo has been its disclosure that Canada has some of the world’s best product designers,” designer Harris Mitchell wrote in Canadian Homes & Gardens. “[T]his is the shape of things to come.”

Hardly noticed by the brave designers who now saw before them one continuous march into the future, was a gradual, subtle shift.

You might have spotted the shift—so to speak—as close as the Expo parking lot, in people’s cars. Artificial wood, a newish but not modern material that simulated the stuffy, the old, was gaining space on the dash, on the door panels, in the interiors of this most technological, more typically forward-looking of possessions.

The truly astute might have seen the signs before Expo. Hindsight suggests they were visible in the Eaton’s catalogue, for instance, where, in the mid-nineteen-sixties, fussy, gold-trimmed, traditional dinnerware was once again displacing the spare modernist wares of England’s Midwinter or Eva Zeisel’s Hallcraft in the U.S., whose styles were the rage a few years before.

You could have seen the shift on St. George Street in Toronto. So recently it had been the harbinger of Modernism in the city, a boulevard of brave new apartment houses by architects the likes of George Boake, Leo Venchiaruitti, and Rhea Shulman’s husband, Wilf, all brash, young University of Toronto graduates. But, by 1964, their more flamboyant colleague Uno Prii—no devotee of the Bauhaus, but a very popular contemporary architect—was erecting, along St. George, brand-new apartment houses in Spanish styles. They featured dark, warmed-toned brick, arches, and brass sconces with wavy yellow glass guarding their entrances.

Barely discernable in their day, these disparate circumstances foretold how Modernism—a set of principles backed by what people thought were important truths about materials, philosophy, functions—was sliding. Signs that, to the public, modern was falling back to being just another style.

In January, 1968, at the Canadian Furniture Mart at Exhibition Place in Toronto, Luigi Torti and Angela Lettieri, soon to be married, “spotted the sofa they would like to have in their first living room. In a rich brocade, with the Italian provincial lines they like,” the Star reported. At the same show, a Canadian firm displayed a new series, Le Moyne, which was “based on furniture fashions of New France 300 of years ago… The series is made of spiced maple. Pin knots and other little distressed wood touches are left to complete the rustic look….Another interesting exhibition is the Hauser Ironworks’ showing of a Spanish dining room.”

Norman Hay, head of design at Expo 67, would later wonder whether the fair had not been the beginning of an era, but the end of one. “Striking are the many references to the numbers of ordinary Canadians who would patiently line up to see specially mounted displays of new [modern] furniture. By the tens of thousands we would be entranced by the streamlined simplicity of these model rooms,” one reviewer wrote, after reading Virginia Wright’s history, Modern Furniture in Canada. “Sadly, one is led to consider just how many would turn out today.”

Reflecting on the 1999 demolition of the J. & J. Brook–outfitted Union Carbide Building, a particularly elegant modern-era piece, Joanne mused about what happens to the furniture when a building like that is decommissioned. “It’d be interesting to know, wouldn’t it? ” The answer lay, to an extent, on web sites like eBay, where old modern furniture is auctioned off as retro, fetching hefty prices, not to mention Queen Street in Toronto, where chic shops with names like Red Indian and Ethel do brisk trade in modern, new and used, high-style and low. And at retail stores like Caban, where repro modern pieces are sold for more than the originals, their attributes appreciated—now as then perhaps—by a discerning but limited portion of the public.

The life of J. & J. Brook bracketed the true modern era almost exactly. The store, moved from Avenue Road to 66 Yorkville Avenue, closed in 1976. The firm’s last large commission was the new Toronto Star building at 1 Yonge Street, a complex undertaking, much altered by 2001. Its unsung masterpiece—the huge, colourful wall-hanging in the lobby, suggesting the flow of ink through presses—was commissioned by Joanne Brook. The artist was Quebec-based Mariette Rousseau-Vermette, creator of theatre curtains at such venues as the National Arts Centre, Place des Arts in Montreal, and the Eisenhower Theater in Washington, D.C.

In the nineteen-seventies, Joanne was contracted by Imperial Oil, handed a half-million-dollar budget, and sent across Canada to buy original Canadian paintings for Esso’s new building in Calgary.

For John Brook, who his wife said had an insatiable appetite for projects, there were many: a line of pottery, designs for jewellery, and Pax Design, a sort of Canadian Georg Jensen, a store in Yorkville that sold native arts and crafts and beautiful imported gifts, all in a modern vein. It survived into the early nineteen-eighties. Not many of these made money apparently; one observer suggested as early as 1962 that John Brook’s success was “more esthetic than financial,” if influential. He “has encouraged others to design and make Canadian office furnishings.”

In the early nineteen-nineties, John wrote a book, Jobs: That’s “What Matters,” attacking the policies of former prime minister Brian Mulroney. Also in that decade, the Brooks lived for a time in Alberta, where John developed training programs for oil and cement companies. He died in 1997.

Public taste moved on, and on, and sometimes went backward. Briefly to post-Modernism, with its tongue-in-cheek historical appliqués, seen mostly on skyscrapers. More permanently, among the wider public, to retro château style, seen on gaudy “monster” or “trophy” homes, built in various grades in subdivisions across the land. The furniture was like the sport-utility vehicles in their driveways—ill proportioned, expensive, and mostly symbolic in purpose.

“What happened? ” wondered Joanne Brook in 2001, in her uptown apartment, surrounded by prototype chairs, antiques, Canadian art, and sculpture. No one would have imagined this future, certainly no one looking in the window of J. & J. Brook on Avenue Road in Toronto in 1960.

They knew what the future would be. It had arrived—it was displayed there in front of them. In furniture that was to the home and office what Brubeck was to jazz or jets to air travel or colour to television—inevitable, true, timeless, beautiful.