Now the sun rose higher and the heat of the day increased. The whole company remained in the pleasant shade, and, as a thousand birds sang among the verdant branches, someone asked Francesco to play the organ a little, to see whether the sound would make the birds increase or diminish their song. He did so at once, and a great wonder followed—for when the sound of the organ began, many of the birds were seen to fall silent and gather around as if in amazement, listening for a long time; and then they resumed their song and redoubled it, showing inconceivable delight, especially one nightingale, who came and perched above the organ, on a branch over Francesco’s head.

Hey, Frank, it said, that’s pretty good, for a human. Why don’t you have another cup of coffee? I know it’s pretty hot out here, but when you pour the milk I’ll have an opportunity to tell you about Bessie, the cow whose milk it is. Why, I’ve seen her conducting, I think it was the Vienna Philharmonic. I know what you’re thinking: you don’t often see a female conducting an orchestra. But Bessie’s different. No one does Mahler like she does, though it’s true they have to stop when her udders get full and she needs to be milked.

And Frank, a word about these other birds here, redoubling their song in inconceivable delight. Well, don’t be fooled. You should see how they act when Stevie Wonder is around.

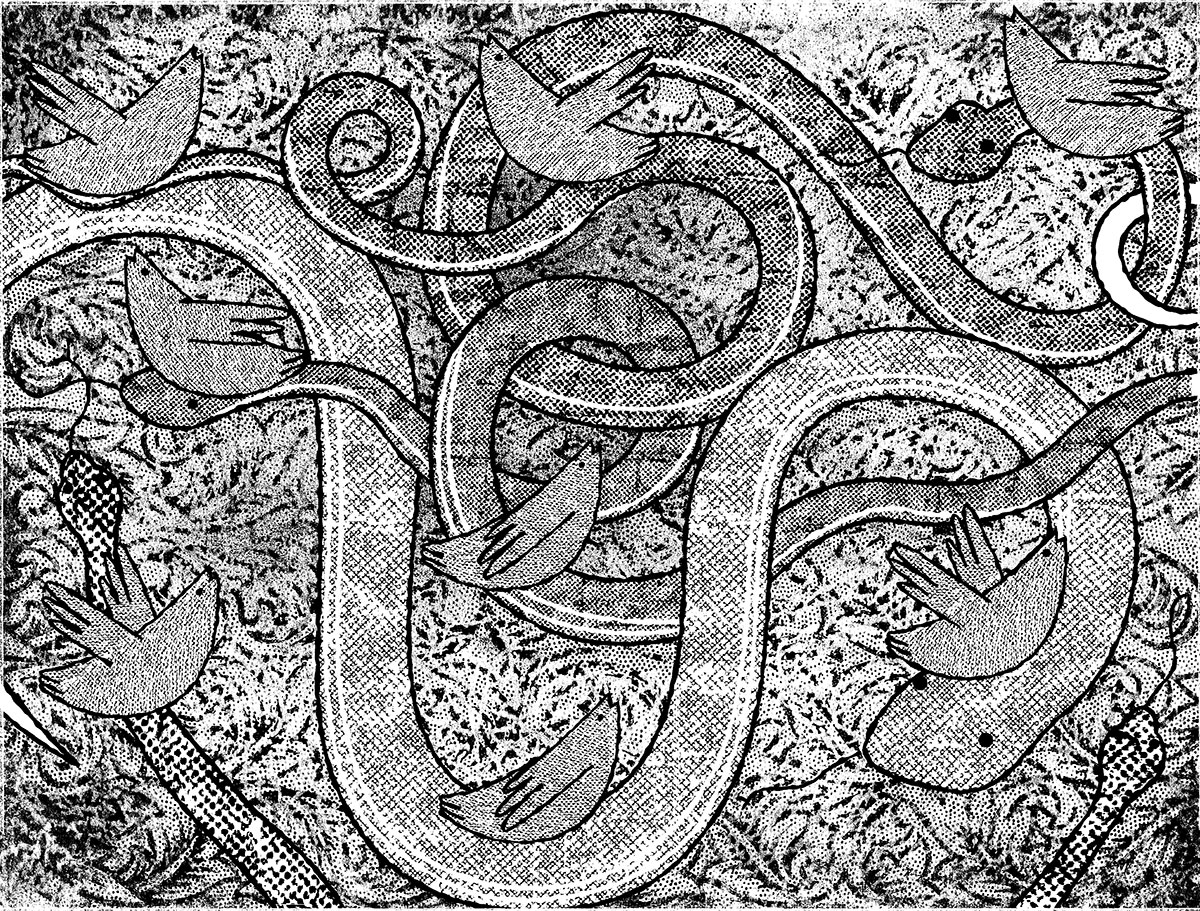

Did I ever show you how I can eat a worm and sing at the same time? Hey, maybe later you’ll come on over to the verdant glade, just past the river, and play Twister with the beasts of the field and the other birds of the air. You should see how the garter snakes make a lattice of themselves, while the sparrows, each of them like a summer flower, bedeck it. It’s really not bad, what with the deer singing their sweet little R. & B. songs and the blind moles coming up from their tunnels underground, dressed in flashy clothes, telling tales of Milan and Ferrara in the sixteenth century.

Anyway, I’ve come to ask about Albert. I haven’t seen him in a while, not since we went south.

It’s like this, Frank. Once, me and a bunch of other birds, a flock really, made ourselves little harnesses hewn of spiderweb and then attached Albert to us with blades of grass. The sun was like a giant yolk in the centre of the sky’s blue egg, and we pulled up into the wind. There we were, speeding over fields, cutting off blue jays, careening around clouds. Albert hung beneath us in his grass nest like a gunner in an old warplane. He was singing and calling out to the surprised farmers in the fields below, “I am the sky’s tractor, a dolphin of the air. I am Pegasus, my wings of nightingale made. Nothing, not even shag carpeting, can soar as I soar.”

And we birds, we knew how he felt. Once, we rode a city bus downtown, and once, some of us travelled the Sea of Galilee in a glass-bottomed boat. A bunch of us have even been in the trunk of a Lamborghini as it sped down the Autobahn. When the driver, a certain Mr. Beerbaum, opened the trunk to get his suitcase, we burst out, each of us carrying an apple in our claws, apples that Mr. Beerbaum was bringing home to his mother, who made the kind of succulent apple pie that any bird would delight in flying out of, as if from the trunk of an expensive Italian car.

All night we sailed across the sky with Albert beneath us. We were a web of birds, and Albert, tied by the sticky threads of grass, was our catch. As the moon rose, the shadows of nightingales flickered across his sleeping face. He was dreaming he was a lawn chair sitting by the pool. Through the living room’s open window, he could hear his wife playing “Midnight in Moscow” on the organ and he hummed along.

By the time we passed over Algeria, Albert had woken up. We flew far above the clouds, hardly moving our wings so that Albert could shave. “Where are you taking me? ” he asked. “I feel like a walnut cabinet, or chewing gum on a basketball player’s chair.”

We birds were in a convivial mood and so we joked with him. “Knock knock,” we said. “There was an Irishman, an Italian, and a Jew. What do you get if you lift a Canadian in the grassy arms of nightingales flying south across the desert? ”

I want you to know, Frank, though it’s hard to understand, sitting here playing organ in the pleasant shade, Albert taught us a lot. He taught us the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner,” told us about Tintern Abbey and Saskatchewan. He explained about salt.

You should know that the time we spent carrying Albert across the earth was a time of song, of quiet speech, of croissants and coffee. We learned how to use a wheelbarrow, a compass, how to make food crisp in a FryDaddy.

And we, in our turn, taught Albert. We showed him the vulture’s ten-speed bike, the tears of the sobbing moon. We explained how to make a dining room table from camel skin, how the jackals like teak veneer. We taught him to recognize Iceland by its shadow, how to cut down trees by sound.

In the time Albert spent below us, he learned what the web-bound chests of nightingales know, exhausted and flying for weeks on only coffee, the occasional croissant.

And yes, have another coffee, Frank. You deserve it. Let me tell you that though Bessie’s Mahler was good, her Wagner was terrific. The tilt of her head, a movement of her broad nose, and they wept for hours in the balconies’ dim light.

In fact, it was Bessie’s idea for us to take Albert over the earth in his cradle. She phoned from a tour of New Mexico. “Take Albert beneath you,” she said, “over the ocean’s bevelled floor. Take him,” she said, “over Europe and across Africa’s blond plain.”

Though presidents and prime ministers have invited us skiing, and we’re consulted by butchers and priests, it was to Bessie we listened that rain-dappled day. A letter was sent to Albert to which he replied, “I will dress as a heavyweight boxer. Frank will play the organ while I’m away. Your voices are like the song ‘Midnight in Moscow,’ performed by mimes. I am not, nor have I ever been. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.”