There’s a book that sat on my uncle’s shelf for years—an evocative, now-obscure memoir, published in 1939, by a French airline pilot. Reading it, I finally learned the inspiration behind the themes of Expo 67, Canada’s famous world’s fair, held fifty years ago, in Montreal. In Terre des hommes (published in English as Wind, Sand, and Stars), Antoine de Saint-Exupéry told of flying the mail between France, Africa, and South America in rickety, propeller-driven airplanes, while also laying out a philosophy of life. He dedicated the English version of the book “to the Airline Pilots of America and their Dead.” In a tragic turn, Saint-Exupéry himself disappeared during a reconnaissance mission, near the end of the Second World War.

Saint-Exupéry might be forgotten today but for The Little Prince, his 1943 novella and one of the best selling books ever written. In it, a chapter from Terre des hommes—the true story of Saint-Exupéry’s crash in the Sahara Desert while flying from Paris to Saigon—is adapted into a magical, child-friendly philosophical treatise. An airman, lost and thirsty in an ocean of sand, stumbles upon a boy who has left his home on a small asteroid to explore the universe. The pilot is stirred by the child’s understanding of life and their shared, deep solitude.

In Terre des hommes, Saint-Exupéry has much to say about the magic of flying, but it was his observations of the planet below that drew the attention of a group of Canadians who, in the early nineteen-sixties, were trying to set the mood of Expo 67. My own life has crossed paths, in different ways, with several of these characters: I interviewed Davidson Dunton, the one-time president of Carleton University, which I attended, and the scientist John Tuzo Wilson, famous for contributing to the theory of continental drift; I lived on the Montreal street named for Wilder Penfield, the McGill University neurosurgeon and a friend of friends; and my spouse taught at Gabrielle Roy, a Toronto school named for the French Canadian novelist.

The group’s initial meeting, at a historic property in Montebello, Quebec, along the Ottawa River, took place in May, 1963. In her notes, some of which were displayed at the Stewart Museum, in Montreal, this year, Roy refers to Saint-Exupéry’s account in Terre des hommes of piloting over Argentina at night and seeing a few flickering lights below. “They ‘twinkled here and there, alone like the stars,’ ” Roy wrote, quoting the author. Roy made a timely connection to the grandeur of earth as seen by the era’s astronauts, who similarly observed “the splendour of Man’s Earth, this one tiny speck fixed in the vastness of the universe.”

Saint-Exupéry and his navigator were rescued from their real-life Sahara crash by a Libyan Bedouin, whom the author thanks in Terre des hommes, as he makes a plea for human solidarity. The book was published at the outbreak of the Second World War. Saint-Exupéry, wrote Roy, “found a phrase to express his anguish and his hope that was as simple as it was rich in meaning.” It was the idea that we shared one earth and should try to get along: terre des hommes. Man and his world. The Expo group took up Saint-Exupéry’s theme of human solidarity, and used his book’s title as the fair’s slogan. It was as if Saint-Exupéry “were speaking directly to the truck-driver, the ditchdigger or, better still, the mason,” Roy reflected, alluding to man—we would now say “humans,” or something similarly inclusive, in all these instances—as builder, creator, and steward of the planet and the civilization he had created.

My parents moved to Montreal, from Burlington, Vermont, a few years before I was born, eventually settling in the suburb of Pointe-Claire. As a child, I lobbied my mom and dad, Sylvia and Clem, to take me to see sites downtown, such as La Fontaine Park, with its aquarium in a whale’s mouth, and Place Ville Marie, the new skyscraper, which had open observation decks. I tried out space-themed playground equipment at the park on St. Helen’s Island, where, at the age of six, from rocket-shaped climbers, I first glimpsed (through a fence) Expo under construction. There was still doubt whether three years would be enough time to ready the fair (a new documentary about the building of Expo is subtitled Mission Impossible). When Gabrielle Roy visited the site, she found “a soggy field” containing “millions upon millions of tons of earth and muck.”

Three years was an unfathomable amount of time to a boy of six, but the idea of Expo registered with me, as it did with most Montrealers, if not yet the rest of Canada. Within a year or two, West Island kids were doodling Expo’s logo—Julien Hébert’s now-familiar circle of stick men, linked in pairs—in their school notebooks. Long before Expo 67 opened, its earworm-y theme song, Stéphane Venne’s “Hey Friend, Say Friend,” was inviting us to “come on over.”

My brother, Jeffrey, two years older, kept an Expo scrapbook as a class project (for which he received a decent mark of sixteen out of twenty), and unwittingly created a valuable future resource. It is one thing to say in hindsight that opening day was magic. It’s quite another to be able to prove it. A few days after Expo’s debut, Jeffrey wrote to our maternal grandmother about it, and I am astonished, fifty years later, to be able to walk with my family through Expo on Day 1.

“Dear Grma,” Jeff wrote on Wednesday, May 3rd, hunt-and-peck style, on an old Remington typewriter. “Expo is open and in five days 2,000,000, 7/8 Montreal’s population, have gone to see it. After school on Friday Alfred, mummy and I left at 3 o’clock because we couldn’t wait any longer. We drove in town by six and four lane hiways. By three thirty we had paid $2.50 for parking and bus fare. At four o’clock the bus pulled in at place d’accueil, the Main entrance. As we showed our passports they let us in. After going over our plans we boarded the expo express, the free transportation.”

Jeff described how we zoomed “past the Habitat Station, past place des nations,” en route to La Ronde; how we “boarded the minirail, a ride carrying you forty feet high and even through pavions”; and how, at the Île Notre-Dame Expo-Express station, “we had a discussion. After having a vote we entered the Western Provinces Pavilion,” in which “we descended into a mine. Here we saw different Rocks mined in Brtish Columbia. After manuvering a sharp bend looking at an Atomic Energy station we took a look at a tipicle wheat farm in the wheat-growing provinces of Alberta, Saskatchwan and Manitoba. Suddenly we entered a roofless room in which a giant log truck and real trees had been planted.” I recall there lingered a scent from what the official Expo guide referred to as “lofty Douglas firs,” even a forest-y dampness, helped by cool weather in Montreal. On postcards, the firs are seen poking out the top of the shingled structure.

It was a packed afternoon. We ended up at the Ontario pavilion, a many-angled, origami-like canopy, and where Lake Erie perch was served in one of the restaurants. Things quickly got more technological. Jeff was impressed by a series of robots “representing M. Busnessman, Mr. Sports, Miss. Arts, Miss. Science,” who put on “a marvolous mecanical play.” But something else blew us away even more: “We were told that a rare film was to start in two minutes,” my brother wrote. “This film turned out to be the only one like it in the world . . . in which different pictures flash on a screen and suddenly turn into one, change and split up again.” That would have been A Place to Stand, with its score “A place to stand / A place to grow / Ontar-i-ar-i-ar-i-o,” another earworm of the day, and from then on an anthem—perhaps the cheeriest ever penned—for the province. The movie’s innovative multi-dynamic image technique helped win it an Academy Award, in 1968, for best live-action short subject.

“By that time it was five o’clock and we decided to leave,” Jeff continued. “But as the bus slowly glided away we thought ‘what an amazing exhibition!’ ”

We would visit Expo often, all summer. I’d look from the parking lot, through the iron beams of Montreal’s blackened, rusty nineteenth-century Victoria Bridge, across to Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, shimmering blue-green in the distance, or Katimavik, the upside-down pyramid, on Île Notre-Dame. This was my world, I thought, and although Expo came and went, in many ways it has remained my vital happy place ever since.

In Montreal, in the nineteen-sixties, young children walked to school alone and wandered unsupervised around their neighbourhoods. My brother, my cousins, and I were similarly free-range at Expo. We were inclined to go to La Ronde, the amusement area, but once let loose, we headed for where it was really at: film screens.

Expo stood as the prototype for the virtual, electronic future predicted by the media guru Marshall McLuhan. The pyrotechnic virtuosity on-screen grabbed your attention and would not let go. Many films were torqued to the limit, using the technologies of the day: multi-screen; cruciforms with images ahead, above, and below; audiences seated on carousels.

The Canadian paint and chemical industry’s Kaleidscope pavilion was called by one critic, “a prismatic environment of reflecting mirrors with filmed images of bleeding, bursting colors . . . the ultimate psychedelic experience”—a very sixties, McLuhanesque way to push paint. The queue to see the National Film Board of Canada’s multi-screen, multi-chamber In the Labyrinth was so long it snaked right out into the St. Lawrence River, at least as seen in a newspaper editorial cartoon of the day. Thanks to the very type of media McLuhan foresaw—namely, virtual reality—my mom and I finally got to see the film this summer, at the Stewart Museum. We were seated in womb-like white plastic chairs, as a young man whose parents, even, might not have yet been born in 1967, helped us on with our goggles. Into the labyrinth we went, finally seeing what the fuss was about fifty years ago.

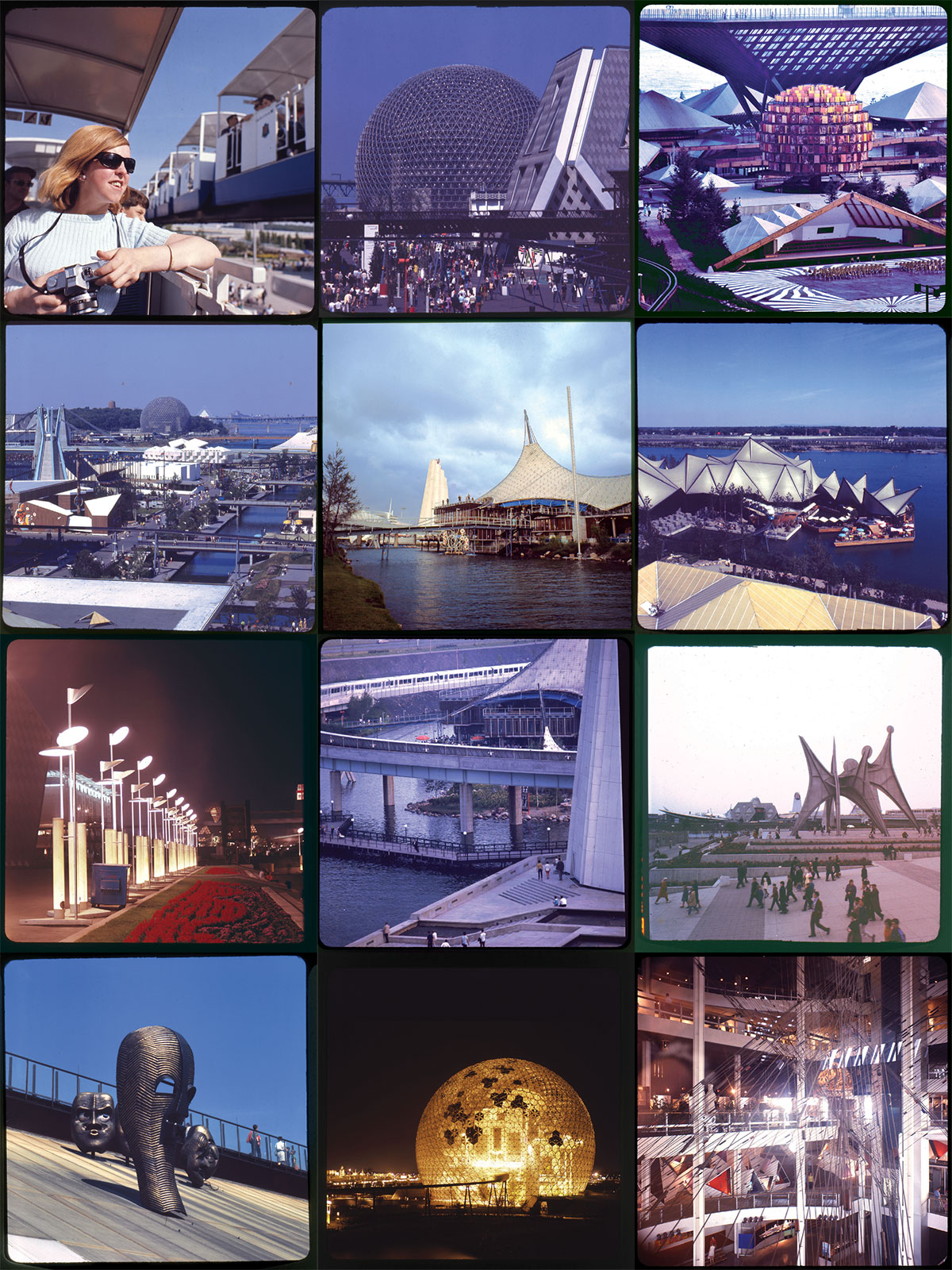

There is one Expo film that wasn’t very fancy. Like many films at the fair, the equipment needed to play it isn’t as easy to find anymore. It was the home movie made by my family. There we are on eight-millimetre film: my mother, my brother, and me (Dad is the cinematographer), ready troopers arriving at Place d’Acceuil, the fair’s entrance. I appear on the platform waiting for the Expo-Express. When it arrives, my father follows me in, camera running, and off we go. Looking past my bobbing head, you see us zip past the architect Arthur Erickson’s Man in the Community pavilion (fashioned from what seem like giant Popsicle sticks), past Habitat 67, the model housing complex. In a moment, we are crossing the new Concordia Bridge to St. Helen’s Island.

My dad pans across the unfolding scene: On the left, the ball of Fuller’s American pavilion. More distant, out on Île Notre-Dame, rises Katimavik, the centrepiece of the Canadian pavilion. Its aqua colour is still visible in the faded footage, shown dozens and dozens of times at family get-togethers over the past half century.

I am seen on a different day, in my red blazer, yawning, in the massive Soviet pavilion, which displayed such doomed technologies as the Tu-144 supersonic jetliner. In another scene I wave frantically for my dad to hurry up, before disappearing into British Hovercraft Corporation’s experimental hovercraft service, which would take us for a spin up the rapids, through Le Moyne Channel, separating the Soviet and U.S. pavilions.

In my overcoat—this scene must have been early, or late, in Expo’s six-month run—I walk up to an animated sculpture that caught my cameraman’s eye. My dad lets the film run, as rotating rings show a jumble of moving colours. They slow down, and I look satisfied as the shapes come to a stop, aligned as a pop art play on Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

In one scene, my older, calmer brother looks out at the St. Lawrence, from the patio at the Ontario pavilion. I show my impish side at Vermont, where I follow my family up a ramp, then walk backwards straight back down, knowing on playback the film will seem to have reversed. Outside Belgium, Dad hands me the camera and everything goes shaky, but Dad smiles as he walks toward me, wearing a suit over his argyle sweater vest.

Two sailors approach as I walk toward Katimavik. We spot a Mountie on a horse, and the People Tree—orange panels with photographs of Canadians on them, resembling a maple in the fall. Thanks to the magic of editing there is no queue, and we are instantly up walking the inverted pyramid’s perimeter, looking across at a giant Canadian flag waving in a wind that shook Katimavik on its steel legs. We look out at Britain, with its tower capped by an upended, 3-D Union Jack. We pan past the Indians of Canada pavilion, as it was called. In the current era of reconciliation, it’s worth reviewing what the Expo guidebook said fifty years ago: “Primarily the Indian people want to present the problems with which they are faced by involvement in a modern technological society, and to affirm their will to preserve the traditional moral and spiritual values of their forefathers.”

In a bit of trick photography, I am seated, with my blue Expo 67 tote bag, on the edge of a precipice. Foreshortening by the camera makes it appear I can reach out and touch the passengers, not to mention the track and electrical gear, on a passing Minirail. Over at La Ronde, La Spirale rotates up its giant pole. Voyageurs paddle a giant canoe on Lac des Dauphins. A man flying on a Canadian flag hang-glider soars behind a motorboat. Finally, I look pensive, exhausted on a replica of Jacques Cartier’s Grande Hermine, the ship he sailed to North America, in 1535. A gondola ride whisks us back to the more serious part of Expo.

In the age of digital video, when any smartphone can produce sharp, instant moving pictures, it is hard to imagine the trouble and expense involved in 1967 to create such fuzzy, flickering memories. A four-minute roll of unexposed film cost about three dollars—the equivalent of twenty-two dollars in 2017. The better Kodachrome stock cost even more. Cameras were finicky, mistakes many. Projectors were hard to thread and often jammed, and the heat of the lamp could melt the film. Ambitious parents edited scenes together, but many families didn’t bother, showing the reels exactly as they were returned from the processor. Our film has at least one Expo-worthy special effect: a double exposure my dad left in of a trip to Vermont the following winter. Skiing at Expo we call the error, where family members are seen disappearing down ski trails at Smuggler’s Notch, darting between moving Minirail trains, ghosts schussing through such impediments as the French pavilion.

Scenes of young Alfred at Expo, from the Holden family’s home movies.

In 2007, I contributed to Concrete Toronto, an anthology of essays on mid-century concrete architecture, published by Coach House Books. At the launch party I rubbed up with a friendly gentleman, also a contributor to the anthology and, as I found out, the architect of an artful addition to Toronto’s Central Technical high school. “A Place to Stand” began to play in my head.

“You did the Ontario pavilion at Expo 67—Macy DuBois.”

“With Fairfield. And it’s ‘DuBoyz,’ ” he corrected me. “I pronounce the s.”

“The pavilion was great.”

“Thank you,” he replied.

Several years earlier, my spouse and I lived in one of Toronto’s early Modernist apartment houses: 169 St. George Street, built in 1958, and designed by James Crang and George Boake. Boake was in the Toronto phone book, so I invited him over to have tea and sit in one of his corner windows. It’s cool to live in a building and ask its architect, as he eats your cookies, what he was thinking. A lot depends on the client, Boake said. “There didn’t seem to be a lot of interference, if you like” at 169. Then he told me client input was considerable for the pavilion his firm designed for Air Canada at Expo, its most prominent feature a spiral stairway to the sky, suggesting the circle of fins in a jet engine.

That was the thing about Expo: my childhood happy place kept turning up in my adulthood, saying hello, with life-affirming regularity.

In the eighties, I ran into Expo daily, at the office. The late Boris Spremo was a Toronto Star photographer who’d covered the fair, although he hardly got to see it, he told me this year, in a brief phone call: “Working all the time.”

Covering city hall I met Colin Vaughan, the crusty commentator for Citytv, who, it turned out, was a principal architect of the Canadian pavilion. Reporting on Ontario Municipal Board hearings for Toronto’s domed stadium, I met the SkyDome architect, and Vaughan’s partner on the Canada pavilion, Roderick Robbie. Reporters sometimes get their best material from small talk at the beginning and end of an interview, and when I spoke to Robbie for something or other, in 1997, the topic of Canada at Expo came up. I let the tape run: “We wanted something lively and light and kind of reminiscent of the country. The general concept was that this airy sort of roof was like this huge sky that you see in Canada, and the land was the brick paving that went everywhere. . . . The form—this square, thirty-degree pyramid—grew out of the notion of unity in diversity. . . . The general idea was to show a country that wasn’t a melting pot, it was a mosaic, and the whole design was based on that. The katimavik was ‘meeting place’ in Inuktitut. . . . I and my colleagues picked the pyramid—the symbol of forever-no-change, almost mindless stability, which sort of characterized the ancient Egyptian culture. We said, ‘If you took that, turned it upside down, and suspended it in mid-air, it would show a number of things. One was great dexterity of balancing the people and the problems.”

My mother clipped and saved a New York Times review of Habitat 67, Expo’s daring housing exhibit, written by the pioneering architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable. “What Habitat is, to the eye, is a Mediterranean cluster of pyramided and jutting boxes that form one-story and two-story houses so that the roof of one box makes the garden terrace of another,” Huxtable wrote. She also observed that “just about every housing and building rule, precedent, practice, custom and convention is broken by Habitat. This includes design, engineering, construction, trade union operation and the way people live. There have been two results. One was snowballing costs and technical problems. The other is a significant and stunning exercise in experimental housing that is also the most important construction at Expo.”

I recall visiting an apartment low in the jumble, with ultramodern furniture, a garden, and views of the river. At the far end, nearer the point of Cité du Havre, one of the concrete boxes was suspended all summer from a crane. Around it were moulds and equipment showing how they were made—a fortuitous display, the result of Habitat being not quite finished by the time of Expo.

My interest in Habitat turned a page in 1971, when Karl Raab, the son of friends of my maternal grandparents, moved from Vermont to Montreal, taking a sublet on Apartment 615, midway up the pile. Here was my chance to visit and stay at Habitat often, sleeping in one of the Raabs’ heirloom Biedermeier beds.

Our extended family gathered at Karl’s apartment in June of 1972 to see Grandma off to Europe on the Soviet ocean liner M.S. Mikhail Lermontov, whose sister ship, the M.S. Aleksandr Pushkin, of the Baltic Sea Shipping Company, was where the Soviet Union had signed its deal to participate in Expo. One picture shows me, sporting an Andy Warhol hairdo, standing with family on the Lermontov’s stern, Habitat behind us. In another, we switch, and watch from the terrace of Apartment 615 as tugboats pull the liner, Grandma safely aboard, from its slip, and it departs down the river.

Alfred Holden, Sylvia Holden, Erna Heininger, and Oskar Heininger, aboard the M.S. Mikhail Lermontov, 1972.

Slides show our family visiting Habitat. Here we are in the nineteen-seventies, picnicking on the patio. There is Eveline Bradter, Karl’s wife (whom he met on the Expo site), on the patio, being stung by bee. She is next to the tomato plants that prospered in the architect Moshe Safdie’s centrally irrigated balcony planters.

The Raabs’ unit contained the famous two-piece molded fibreglass bathroom—tub, sink, ceiling, and floor all one prefab unit, everything but the toilet, which was bolted to the wall. The apartment also had a General Motors Frigidaire kitchen, elegantly modern, with grey cabinets framed in aluminum. I loved Habitat so much, my instinct was to move in. In another instance of Expo resurfacing in my life, I almost did. I was twenty in 1978 when Eveline, who worked in the German Foreign Office, was transferred to Vancouver. Between us we conceived a scheme to hold onto Apartment 615 by subletting it, but the deadline to give notice to Habitat’s owner, Canada Mortgage and Housing, passed before we found a tenant. A few years later, the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sold Habitat, for ten million dollars, to Pierre Heafey, a Quebec businessman, who flipped it to residents for $11.4 million. Could we have bought 615, now a condo? By the mid-eighties I was established in the workforce; the Raabs owned a house in Vancouver, but were living in Europe. Maybe.

“It was a feasible plan,” Karl said recently, on the phone from Vancouver.

“It could have worked out,” I said.

Karl told me that when he and Eveline were at Habitat, “I said to her, ‘We will never live as well as this again.’ That’s still true.”

Habitat, circa 1976.

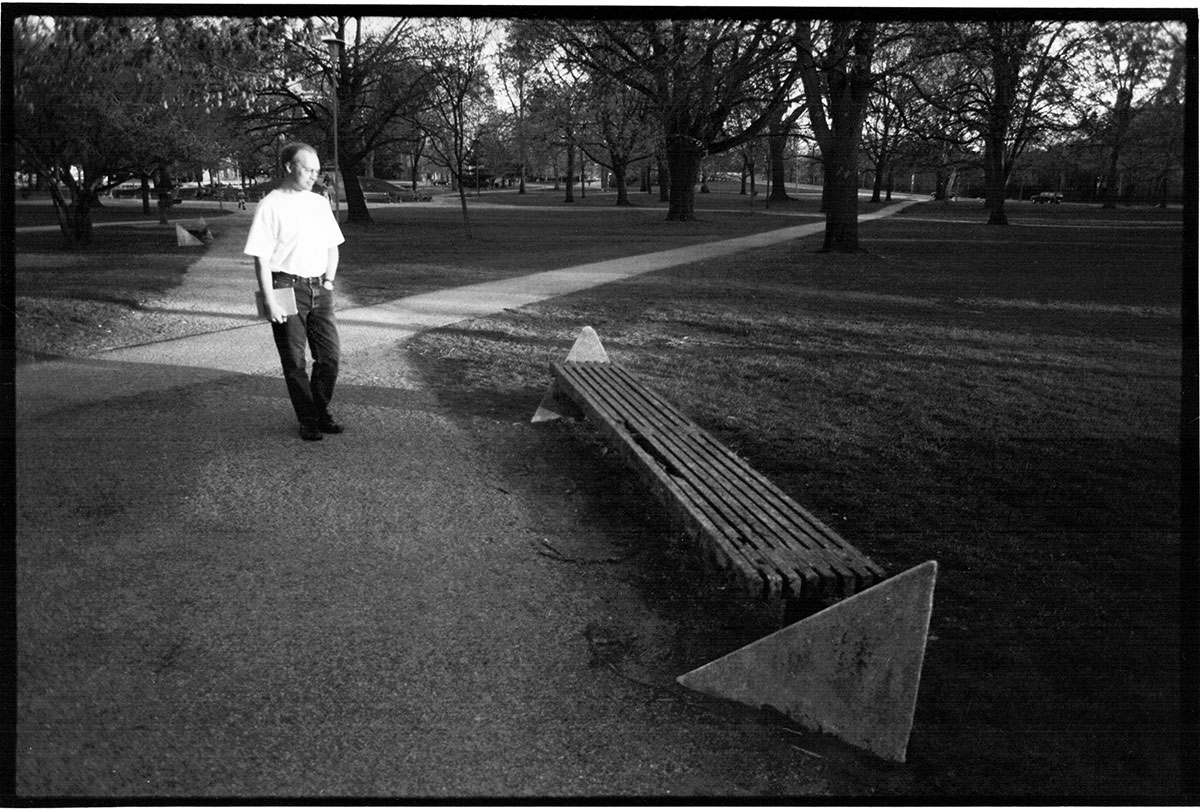

In 1981, after I graduated from university and moved to Toronto, I noticed Expo 67 street furniture scattered around the city, specifically the fair’s distinctive park benches. There were several in Queen’s Park, and a few in the Beaches. Some deluxe ones, with backs, lined the tiny Frank Stollery Parkette, at Yonge Street and Davenport Road. Fourteen years after Expo, I thought myself to be one of few people who knew or cared about the history behind them.

During the summer of 1967, my mother noted discrete plaques attached to the avant-garde furniture throughout the Expo site. The signs indicated the benches were Toronto’s offering to the fair. They were part of an ensemble that included matching triangular trash cans, broad white disk-shaped street lamps that reflected light projected from below, and bubble phone booths, all custom made, and credited to the designer Luis Villa. This didn’t much please the Toronto designer Paul Arthur, who created Expo’s much-acclaimed signage, and who originally held the furniture contract.

It seemed logical that Saint-Exupérian sentiments about human interdependence, McLuhanesque notions of a global village, or maybe even Jane Jacobsian expressions of friendly urbanity would be behind Toronto’s Expo benches—but was it so? As a Torontonian now, I was curious. In some old city council minutes, I came across a mention, along with the name of an Ontario Expo official named Allan Rowan-Legg. One evening I called him up.

“Yes?” he answered, picking up the phone in Victoria. “I’ve just got into bed but I’m wide awake.”

“I’m calling about the park benches that were used at Expo 67.”

“Well, I know all about them.”

Rowan-Legg was one of the lieutenants on the Expo team in Toronto, whose responsibilities included Macy DuBois’s pavilion. He said he’d been given a floor in Toronto’s then new city hall, to drum up interest and Ontario exhibits.

“I went to the mayor [Phil Givens], who was a friend of mine in Toronto, and I said, ‘What are you going to do for Expo in Montreal?’ ” Rowan-Legg told me. “He said, ‘We don’t have any money to put into Expo.’ I said, ‘Tell me, do you buy so many garden seats?’ He said, ‘Oh yes, we buy so many every year.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘why don’t you allot them to Expo 67 and put a plaque, a little brass plaque, on the back, and have them returned to you.’ So that’s how they got to Expo.”

After Expo, the seats were collected, shipped to Toronto, and placed wherever needed. It was something of a scandal in Montreal. In my uncle Oskar Heininger’s slides of the Expo grounds in 1968, there is no place to sit down. Toronto, as Rowan-Legg explained it to me, would have contributed nothing without his manoeuvre: “They were always jealous of Montreal because they thought that Expo should have been on Centre Island, in Toronto.”

In 1997, in my City Building column in the Annex Gleaner community newspaper, I wrote, “Let me recount the story of a glorious summer, as it was told to me by a park bench I sat down on a few days ago under an oak tree. . . . The tale told here quietly, and a little sadly, is one of hope and celebration, mingled with amusing parsimony and competitive rivalry between two great cities. For these are not ordinary park benches, but former ambassadors. They are the street furniture that was Toronto’s contribution to Expo 67.”

At the time, Expo benches could still be found in parks around Toronto. I know of none remaining today.

Alfred admires Expo benches in Toronto’s Queen’s Park, 1997.

Expo was still going full tilt on Labour Day, 1967, when my family moved to Ottawa. My dad had taken a job at Parks Canada, and we purchased a house in the Glebe. Back in Pointe-Claire, 110 Douglas Shand was sold, with the closing at summer’s end, giving us and family visiting from the United States some more time at Expo. After the move, we commuted by Volkswagen from Ottawa. In my dad’s Expo Passport—the season passes fairgoers had stamped at each pavilion they visited—he noted “26/10/67,” two days before the fair closed, and the last day the Holdens were there.

This past August, my spouse and I took our bikes to Montreal and did the grand tour of what is now Parc Jean-Drapeau, the former Expo islands. Its symbol is Julien Hébert’s globe of stick men. We had to laugh when, cycling way out on one of the narrow strips of fill in the river, we ran into the short-lived black gnats that gather in extended clouds along the St. Lawrence, whom officials prior to Expo went after with the best insecticide they could find—dichlorodiphenyltrichlorethan, or D.D.T.

Remnants of Expo abounded. On St. Helen’s Island, we passed through the sculpture park that was a lively part of the Expo art scene. Some pieces remain, unsung in the maturing forest, while others are sprinkled about the islands. They include, on St. Helen’s, Alexander Calder’s Man, moved from its original site. We passed the geodesic frame of Fuller’s dome, as a security guard in a Jeep kept watch. A fire in 1975 destroyed the plastic enclosure, but the structure of metal tetrahedrons looks sharp just the same. The Canadian flag was flying inside, where the Montreal Biosphère environmental museum has long occupied the complex.

Over on Île Notre-Dame—past Trinidad’s tiny pavilion, lonely amid maturing conifers, past France, past Quebec’s mirrored box, now playing support for the casino—Katimavik is three decades gone. More earthbound sections of the Canadian complex remain, serving as park headquarters. We ran into a wedding party looking for La Toundra, the Canadian pavilion’s Inuit-themed restaurant, where apparently they were expected.

Calder’s Man and Habitat, in 2017.

Touring the remains on St. Helen’s and Île Notre-Dame, it is tempting to lament, to feel loss at Expo 67’s distance in time, to be sad that weeds grow under Calder’s masterpiece. But no less a mind than Pierre Dupuy, Expo’s commissioner general, foresaw another, more virtual, reality. His thesis was that the physical fair itself would be but a corner of what it meant to the nation, the world, to people who went there, afterward. In a form “less glittering but more profound,” such an event “begins a new life . . . nourished in the souls of those who visited the Exhibition, and it will blossom into a legend for generations to come.”

I am the poster boy for the notion that Expo 67 morphed into a foundation for life since. Others coming of age may have relished sports, or maybe found their engagement and glory later in business or academia, or even gone into the army (though the Vietnam War was invisible in Fuller’s American dome). My central reference point has been Man and His World, for all the hope and beauty that Expo 67 represented. “J’etait jeune—9 ans,” I wrote in broken French this past summer, in the comment book of the McCord Museum’s retrospective Fashioning Expo. “Mais je rappelle tous.”

I remember everything.