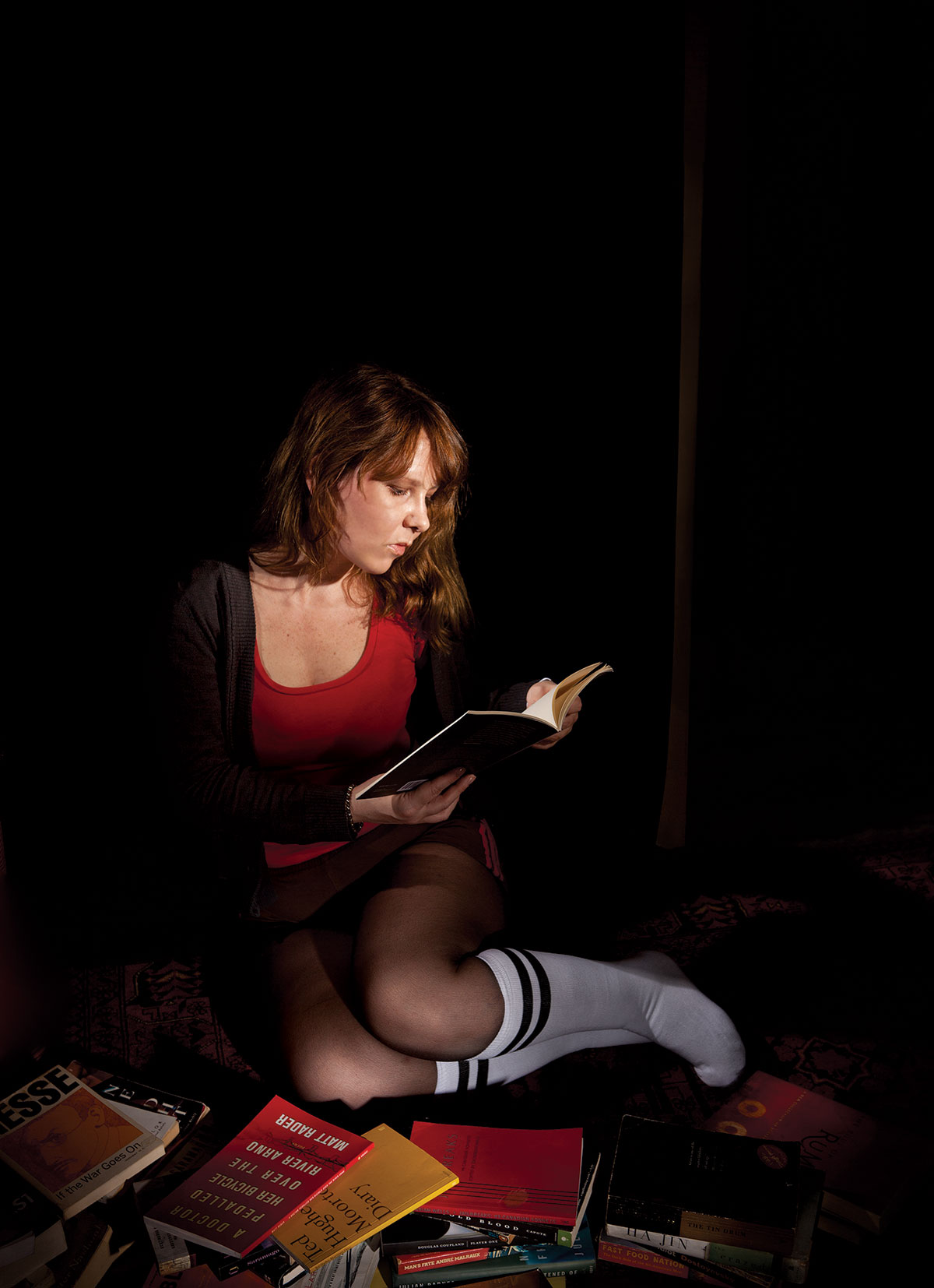

Evie Christie is the author of the poetry collection Gutted and the novel The Bourgeois Empire. The Necessary Angel Theatre Company staged her adaptation of Jean Racine’s Andromache in June, 2011, as part of Luminato. She discussed her debut novel and the play with the poet Meaghan Strimas.

Meaghan Strimas: One of the things I noticed as I was reading The Bourgeois Empire is that you wrote the book in the second person. That’s something risky, and not done often in literature. And coupled with that there’s a real density to the text because there’s very little dialogue. Why did you decide to write the book in that way?

Evie Christie: I didn’t set out to write it any particular way. There was no strategy. I was just writing the way I thought Jules [the book’s central protagonist] would think or speak. He presets himself as a character in sort of a natural way. So there was no outside thought about how I was going to write it—it presented itself that way, and that’s how I wrote it. And I don’t know if that’s something that adds to the reader’s interaction with Jules, or the way they feel about him, but I think, in a certain way, I didn’t want to be somebody who was judging what he did. I didn’t want to feel like I was narrating Jules’ life. That sounds funny, but I wanted Jules to present himself and present his case. And the reader sort of has that relationship with him, and also with not excusing the things that I’m writing about. It’s pretty direct from the beginning, and I’m not cloaking the monstrous things he does.

As for dialogue, I hadn’t really thought about it. Jules is in his head so much that dialogue didn’t come up very often. He’s so self-centred, and most of the book revolves around what he’s thinking and things that he fears and memories. So dialogue didn’t seem important to me throughout the text in the same way it might in another text.

M.S.: Jules is all kinds of things that we should abhor. I mean, he’s a drunk, a pill popper, and all those illustrious evils. He’s a pedophile, right? And not that I want to emphasize that about his character, because he’s so much more, but he’s a crappy husband, an absent father, and completely self-absorbed. He has built this life of comfort for himself, but basically wants to dismantle it, even though he doesn’t even have any clue about what his vision of happiness would be. When you have a central character that has the potential to be so avidly disliked, how did you navigate that? How did you make it so that the reader simply doesn’t turn off and say, ‘Enough is enough. I’m not going to continue on’? Readers are compelled to follow Jules on this sad journey, and we still feel sympathy for this character we might otherwise be compelled to dislike.

E.C.: While I was writing the book, I was at home with my daughter, and one of her favourite movies was La belle et la bête. And there was a line in it that could be a throwaway line where the Beast says, “I have a good heart, but I am a monster.” And I thought so much about that line. I saw the movie a million times—kids are obsessed with repetition—and I thought that sort of summed up a lot of how I felt about being a person myself. I thought a lot about the people I love and the men I love and these monstrous things that we do. The bad father thing is something that…you know, we don’t want to be bad parents, but we’re going to be. We’re going to find out that even these seemingly great things that we have done in raising our children maybe aren’t perfect. We all have crutches, and we’re all probably bad at being partners and being friends in a lot of ways in our lives.

I was also thinking about how much agency we have in our lives, in what we’re doing, and not to excuse Jules in any way, but how much we can control those things we want and things we think we need. We have a character, the girl Charlie—she’s not a stupid person, and I know that I’ve been a Charlie myself. I think she’s a smart girl, and I think she’s sexually aware, and I think maybe she’s more savvy and manipulative than I would have been coming from a small town.

But I don’t know if I made Jules likable to the reader. I think that’s good. He’s human. He’s human in the way we all are—and we’re all weird, and we all do bad things, and we’re all perverse, and those things to me are fine. I can love somebody who has all of those faults. I don’t think he’s likable to everybody.

M.S.: Let’s talk a little bit about Jules and the mid-life crisis. We have a character here who is going through one, whether or not you think that such a crisis can be a path to redemption and feeling alive. There’s this certain idea in the book, I think, that comfort can be equated with a stasis and lack of growth in character. Is it a shakeup like Jules’ dismantling of comforts that can lead a person to a kind of “real” life—the actual feeling as if you’re existing and being human rather than mulling through day to day.

E.C.: The mid-life crisis gets mentioned a lot, and I think I even wrote the term into the book, but I wasn’t fully aware that he was having a mid-life crisis, even though he obviously is. I think probably I’ve had so many of these moments of existential failure where you’re not feeling alive and you do things you probably shouldn’t do.

I sort of thought of Jules as a brave character because he had a lot to lose and he wasn’t completely aware that he was going to lose these things. And when he finds himself free, it’s a much worse state than he could have imagined, but I think it’s a brave thing to follow that course and to find out what your ideas on really being in love are, or really living life. It’s definitely braver than staying in a marriage you’re not happy with, or a job you’re not happy in. So I guess I do think that these crises…they’re not meaningful in any objective way, and they’re not going to have a good end result. I think about so many things we do in our lives, we make these changes, or breakups, and there’s no good result, no good end, but they’re either the right thing to do, or just being true to who you are.

M.S.: I read a National Post review of your book, by Alex Good, and one of the things he noted is that in a sense this story is Jules’ wife Nadine’s story. At first I didn’t buy that at all, and in a way I still don’t, but I think maybe what he was getting at is the fact that while Jules is going through all this turmoil and striking out against this life of middle-class comfort he’s built for himself, Nadine seems comfortable and is thriving in it. He’s perplexed that this is O.K. for her—this sort of unhappy existence, in a sense. I guess maybe what we uncover through the brief conversation at the end is that all along she’s been fully self-aware. She’s been making the best of a bad lot. So in the end she outfoxes him, and has had the upper hand the whole time. I wanted you to talk a bit about Nadine, seen through Jules’ perspective the entire time.

E.C.: I think all of the characters in the book are smart people, and I wasn’t smarter than them or morally better than any of them. I think the funny thing is that we want to say “poor Nadine” when we read Jules, but the great thing is that we don’t have to say “poor Nadine.” That’s what I think is so good about her as a character. “Poor Jules,” I would say in a way. We never feel empathy for these bastards because we think they’re sort of living the life, but Nadine found the life she wanted and Jules is in the life he didn’t want, so I do kind of feel for people who get themselves in those situations. I don’t know about whether it’s her story. I think she’s a strong character, I think she’s what we’d want to be as women. She’s very relaxed and content and the bourgeois person people aspire to be, but probably won’t be.

M.S.: In your poetry and your prose you write a lot about love, or the lack of it. And at one point in the novel the narrator says love makes you sick and socially retarded. But love, at least at the beginning, does make you sick. I think when we’re falling in love with someone there’s a sort of nervous craziness as we try to be exactly what we think that person wants us to be. Does all love eventually kind of dry up, and that’s why we have to move on or shake things up to feel like we’re still alive?

E.C.: Love is kind of a psychosis and what we do in love is not normal. I think love is a term I haven’t pinned down myself. I don’t know what we’re talking about when we’re talking about love yet. I think Jules’ problem is my problem. You asked before, can you stay true to one person or do you need to move on in order to experience life. I don’t know. I have no idea if you can stay true to someone.

M.S.: Do you think Jules actually loved Charlie, or is it the idea of her that he loved?

E.C.: I don’t know. I think Jules loves Charlie, if love is what he thinks it is. And I think he knows he’s fond of her and it’s a good thing while they’re together. In that way, he does love her. And it’s arguable that he also loves Nadine. He feels good things for her, and he’s attracted to her, and he stays with her for a long time. If love means being able to be in a hotel room with someone for three days and not go crazy, then he’s in love with Charlie. It’s a difficult question.

M.S.: You’ve said that your transition from writing poetry to writing prose was natural for you as a parent, and I just want you to elaborate on why you felt the writing of prose was something more doable for you in your daughter’s early stages.

E.C.: I think it’s fair to say children are fairly relentless creatures that need all of you all the time for a certain amount of their lives. It’s difficult to sit around watching YouTube videos. It’s difficult to waste a day staring and thinking and eventually getting to writing, and also a lot of the time when I’m writing poetry, I think a lot of people experience the calm that comes to you over time while you’re doing things like walking, or menial daily tasks. I didn’t have that time to be in my own head. So, when I went and sat down to write, I didn’t have those stored images, words, and lines that I wanted to go to, and I started writing prose just sort of naturally.

M.S.: Is it easier to inhabit another character’s head?

E.C.: Yes, exactly. You have that sort of relentless inner dialogue going on when you’re in that position.

M.S.: So, you’ve written this novel, and you’re now working in the world of theatre. You’ve written an adaptation of Racine’s Andromache for Toronto’s Necessary Angel Theatre Company. I just wanted to wrap up by asking you about making that shift from working in a solitary environment to working and collaborating with a whole crew of actors. What was it like? What did you find beneficial about collaborating with many people?

E.C.: First of all, I didn’t intentionally go from poetry to a novella to a play. I was approached with the opportunity to work on the play with Graham McLaren, who’s the director, and it sort of worked out that we worked well together. I’m sure anyone around me at the time would tell you I felt sick about it. I was nervous and worried. But being in the presence of Graham and those actors—people like Steven McCarthy, Gord Rand, and Chris-topher Morris—just really smart people, it made it easier. They are funny and professional and brilliant. The interesting thing about working in a collaborative environment is that you share moments with others that make you rethink everything you’ve done and the way you thought about what you’ve been writing. There’s no pretense. The director really sets up this environment where people feel free to express their ideas. Graham taught me how to adapt the play. It wasn’t a natural step for me. That collaboration has been incredibly helpful.