Because my desk is a horse, the world is my office. Yes, these mountains are inbox and out, the sky a glass ceiling. I receive E-mails from the dust, poorly written spam from desperate tumbleweed. I am neither cowboy nor Indian, methane wrangler nor native. This all happened so long ago it might well be the future, for I was a young man, just a girl, a flash of lightning from the midnight tinderbox, my world the edge of the world. I’d left both future and past, stole a palomino, rode out beyond the horizon and into the short corridor of the present. Buzzards and vultures circled the cooler, hankering for my weak nerves to expire. Instead I throbbed like a sorrowful thing and the sun sent memos direct to my temples, boiled my spine.

“Hey, good lookin’,” I said to the cracked river, but it had gone to lunch.

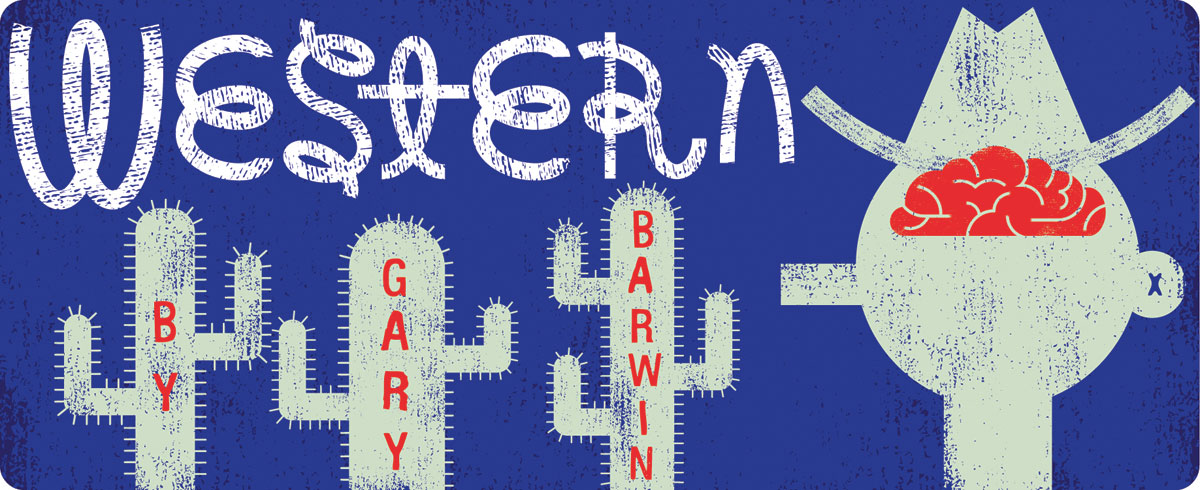

Late night, I played mouth harp as the taxicabs burned and I heard streetcars howling. I got a sidekick: my own brain, and it didn’t always listen but spoke short and laconic and was sometimes eager. What do we hope out here beyond hearing and where the coyotes invest in diversified lamentation?

“Well, Brain,” I said. “We’re here to set up shop as heroes and now it’s time for some cold calling the helpless. Civilization’s stelliferous veneer is thin and happenstance can grit like sandpaper. We’ve travelled this moving dirt sidewalk to be shellac on hard times.”

My brain said nothing but nodded as I nodded and raised my hat to possibility. It was all around us, hiding in plain view. The world was on hold and we’d find its flashing button.

It was Rabbit that first came to us. We shot and skinned him and ate his warm breath.

“Rabbit,” I said, “you and I, and of course, my brain, are one, and in my human canyon you are fire. Look around for I have eaten your eyes and with this dinner of flesh there’s possibility everywhere. We’ll not starve before we have saved.”

“Now, Brain,” I said, “we are well fortified for adventure. Let us find some.”

Brain said nothing but steeled himself as I steeled myself and scanned for what was to be. We looked beyond inbox and out and past the great boss’s hallway, but there was nothing. We looked again and there remained nothing.

We were visited then by many dry days and then weeks more of desiccated impossibility. Insides became as tongues cross-hatched like boot leather. The gut was a black rock rolling in place like dry thunder. Bones ached like dry thunder, also. Great doubt came upon us and we heard the muttering of despair in the next room.

“Keep it down,” I said. “We’re trying to work here. We aim to be heroes before our mortal end.”

Second, it was a ghost which found us, all those vapours of what we wished would be.

“Ride further,” it said. “Find more days in your weak bones.”

It wasn’t lost on Brain that this goading spirit was but voice and no bones, advice but no meat. I remembered Father calling me to his knee and opining, “When there’s no fish and no river, cast down your rod and ride to the next valley with a gun.” Ah, gun, my handshake of fire. I breathed in the ghost’s tobacco guts as if it coiled from a pipe, closed my eyes, and began to think of the respite which awaits at the end of days. But Brain spurred on my weak horse, my soft hands and weak will, and we travelled slow into the next day which was pink folder of opportunity. Or perhaps I should state that there were many people looking like work to be done.

“We have rode far beyond the previous end of our own story to rescue you from yours which is possibly grievous or sorry,” I said. “We hope to relieve pain or misfortune, to allow the waters of ease and comfort to flow once more through the difficult rivers of your life.”

When we awoke, we found our body tied to the wheel of a large wagon and the sun slumped russet over the edge of day. Brain was suffering contusions of his perception and I felt as a carpet must surely feel after a sound dusting. Our senses, except for those supplementary to suffering, were in great disarray. Finally, I remembered my hand, intending next to discover my gun. I learned then that I was birth-naked, and Brain, without hat, was covered only by skull.

I became aware of a great muttering.

“We are planning something of a fricassee,” one of the mutterers explained. “Our intended meat is to be yours.” If fear and low feeling could have lubricated my beef-jerky eyes, I would have wept, but instead my lids burned and I cried out, “We have come to this place because our business is in proffering aid to those in despair. We entreat you to spare our sorry flesh and choose another for this meal.”

There was some chuckling, which I later learned had its source in a traveller named Theodora.

“We intend not to dine upon you, but to offer you sup of flesh for your maintenance. Surveying you now, we see you but are gristle, despair, and starvation. Once you find hope and attain some worthy steak, we shall feed you to our god who lives in the cave.”

She pointed to a black stain among glowering hills.

They fed me then, great red gobs of fat-ripe bone and muscle and I was as one gasping for air who had previously been under considerable water.

“We thank you, Theodora,” I said. “We have returned from a dark and hungering place.” Brain awoke then, buoyed by vitamins and joy and commenced his crafty calisthenics. We would feign sleep, in silence gnaw our restraints, and then ride away by moonlight. It was then we understood we had eaten our horse.

“Sorrow not,” I told Brain. “Our blood runs with gallop.”

Tied to the wheel, we lay still as if carrion, awaiting the sleep of our captors. In darkness we gnawed and with stealth we crept beyond the circle of wagons and toward freedom.

The moon in its office of stars was the third thing that found us, alone on the plain, uncertain of our direction but charged with our vocation to seek the correct path.

“Moon, memo to what must be, advise us of the way forward. Outline with your incisive silver our tasks and responsibilities, our role in the structure of this world.”

The moon shone over the buttes that were as overturned chairs but said nothing. Its bright light searched our soul and we remembered and sorrowed for our lost steed, the desk of our ambition, the outcomes projected and wished for. And then, we felt as much as understood that we toiled within the vast office of the possible. There was work to be done and we would attend to it, attaining deadlines both personal and metaphysic. We would be known as heroes, for it was heroic to have such courage, to wish for such toil. And we would remain in the world, if we must, long beyond closing and far into the moonlit night, our sleeves rolled, our coffee cold in its cup, the world quiet, a brain and a body in the emptiness straining toward destiny and a story of our own making.