Nightview, New York City (1932).

In 1921, Berenice Abbott departed New York for Paris. She had arrived in Greenwich Village, via her native Springfield, Ohio, two years earlier, after an ill-fated start as a journalism major, at Ohio State, and soon developed an interest in sculpture. Abbott hoped Paris would be more nurturing of her talents, but initially was forced to support herself as an artists’ model. A year later, she volunteered herself as a darkroom assistant for Man Ray, the Surrealist photographer, who had also just relocated from New York. Working with Ray, Abbott’s artistic leanings moved to photography. She taught herself both camera and development techniques and began shooting portraits herself, preferring unadorned, straightforward poses to Ray’s dramatic setups. She opened her own studio, attracting intellectual stars such as James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, and her benefactor, Peggy Guggenheim.

When Abbott returned to New York, in 1929, she discovered a city undergoing a dramatic facelift, as nineteenth-century buildings were being razed to make way for Art Deco–style skyscrapers. Seeing the city almost literally being torn down and rebuilt gave Abbott a new vision and perspective. Skyscrapers suddenly allowed her a new vantage point that the Paris of the nineteen-twenties hadn’t.

Unlike Abbott’s contemporaries of the era, such as Weegee or Walker Evans, who discovered their muses on the streets, Abbott kept her unsentimental images focused on the physical city. Her best-known photograph, Nightview, New York City, is a dynamic, almost claustrophobic aerial view taken from a top floor of the Empire State Building. Shot on a large-format camera with a meticulously calculated exposure, Abbott timed the image for late afternoon on the shortest day of the year to capture the warm glimmer of office lights.

Abbott spent six years independently shooting the cityscape until, in 1935, she received a Federal Art Project grant—a program under President Roosevelt’s Depression-era Works Progress Administration—which she used to create Changing New York, her document of the city’s urban transformation. Eventually, her curiosity was piqued by science. Likely inspired in part by Ray’s Rayographs, which visually captured an object’s energy wavelength directly onto paper without the use of a physical camera, Abbott’s self-funded experiments led to geometrically stunning images of soap bubbles, swinging pendulums, and bouncing balls, created in part with equipment she invented herself. Abbott was “trying to make visible invisible phenomena,” says Gaëlle Morel, the curator of the Ryerson Image Centre, which recently obtained Abbott’s archives. “How do you make abstract things accessible to people? It was also fascinating to her that science can be visually attractive.”

In the late nineteen-forties, Abbott’s scientific work caught the attention of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which used her photographs in a physics textbook that came to be considered groundbreaking in the field of education. Abbott continued working as a scientific and freelance photographer until the mid-sixties, when her health began to fail, forcing her to leave behind her muse for Maine, where she lived quietly until her death, in 1991, at the age of ninety-three.

Morel became acquainted with the previous owner of Abbott’s archive, Ronald Kurtz, while curating an exhibition of Abbott’s photography, hosted jointly by the Ryerson Image Centre and the Jeu de Paume, in Paris, in 2012. Kurtz, a high-tech entrepreneur, purchased the collection directly from Abbott, in 1985, when the photographer could no longer take care of it. When Kurtz realized the archive was too much for him to handle, he began looking for an institutional buyer for the more than six thousand photographs and seven thousand negatives Abbott had shot over her prolific career—along with glass plates, books, personal ephemera, and equipment. The collection eventually was purchased by a group of anonymous donors, and presented to the Ryerson Image Centre.

“Berenice was a very independent woman,” said Morel. “This is really a personal collection that reflects her life. When you look at her work, you can see the evolution and the development of the entire photographic medium.”

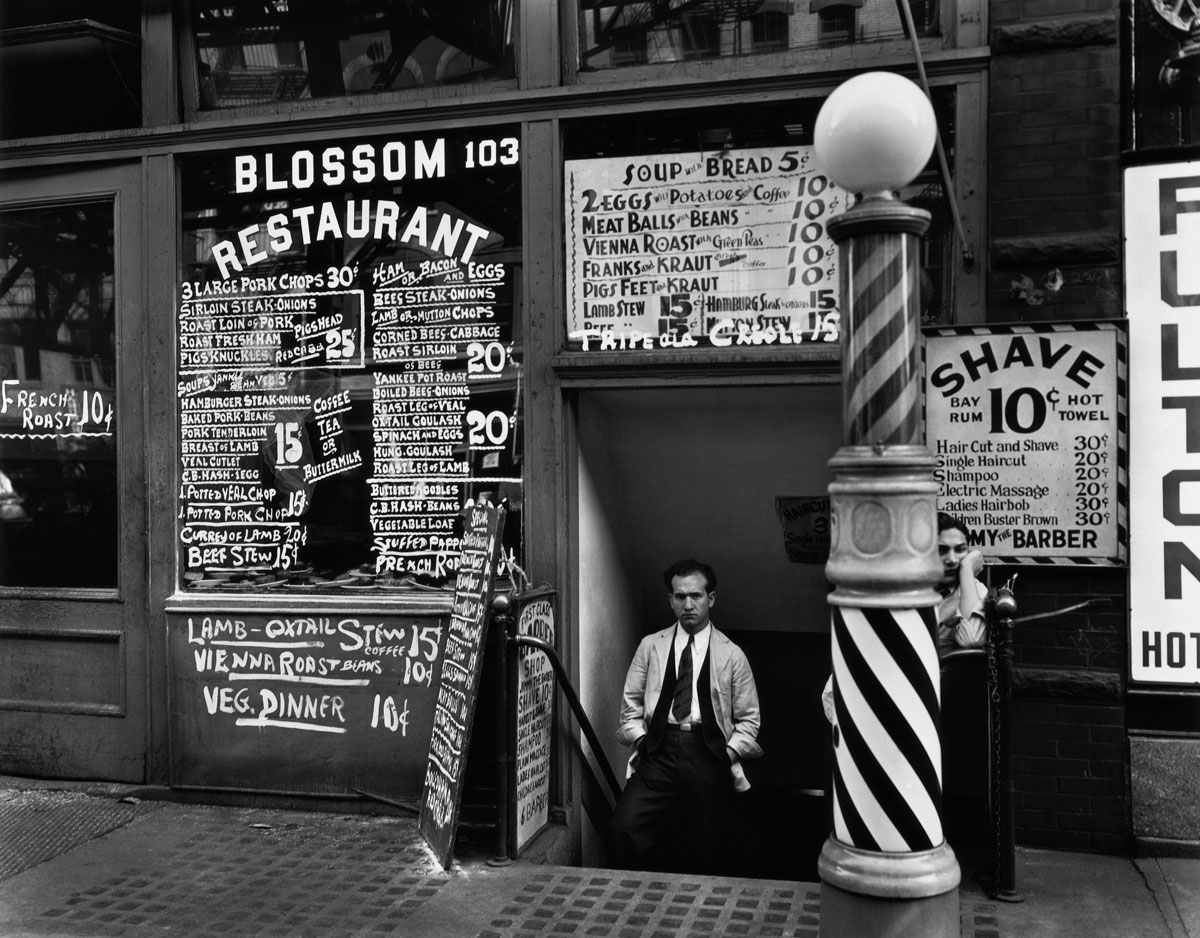

Blossom Restaurant, 103 Bowery, New York City (October 24, 1934).

Eugène Atget, Paris (1927).

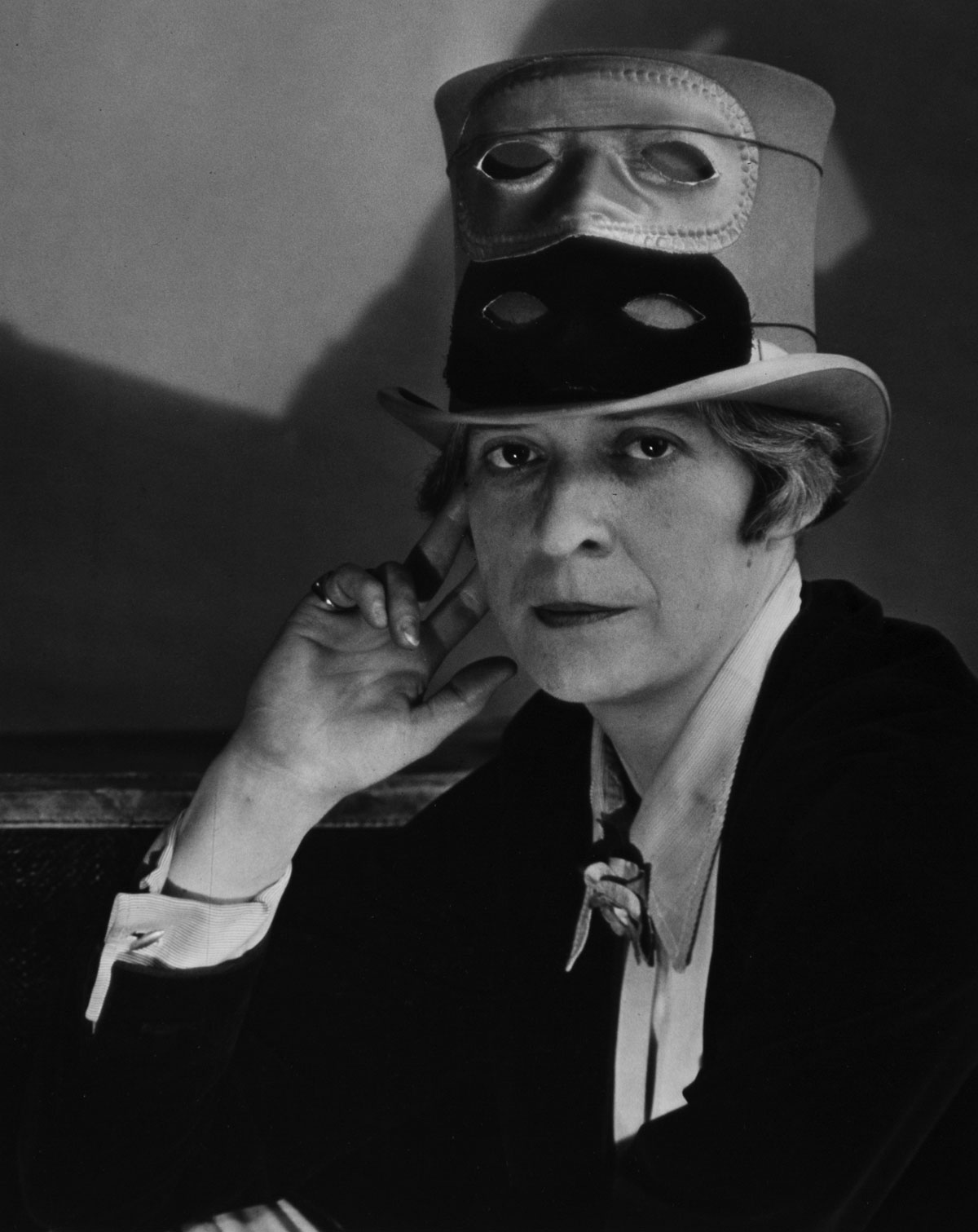

Janet Flanner, Paris (circa 1927).

Newsstand, 32nd Street and Third Avenue, New York City (November 19, 1935).