In the lobby of the Falcon Motel, a young Spanish woman leans on the front desk, snapping her bubble gum. Her dirt-brown hair rolls with curls. An orange-and-red scarf keeps it off her face. Squeezed into a lilac tube top, her breasts are full like her hips and she bares her belly button without shame. She paints her fingernails gold. I clear my throat. She looks up, then down. I tell her there’s people spying on us from the rooftops. They’re wasted, I tell her, desperate. A hundred eyes leering through our window.

She says, “Close the curtains, señora. Turn off the lights. People on rooftops.”

A stocky, ebony-skinned man comes in from the outside. Looks at me through the corner of his eye and sneers. He mutters something to the young Spanish woman. She giggles and snaps her gum. I shiver from standing barefoot on the cold clay floor. A gecko scurries by, missing my toes by a hair.

Back in the room, I study the window. The people have taken a rest. Returned to their families, their jobs. The rooftop is barren but for a single clothesline, one white sheet floating in the wind. I had ripped down the curtains to make a new dress. I neglected to consider the consequences. I wanted a new dress. The heavy fabric laden in daffodils and baby’s breath promised warmth and comfort, some style. I had yearned for a change. Sickened by my unwashed Everlast sweatpants and your Fruit of the Loom undershirt. There was a time I was so pretty.

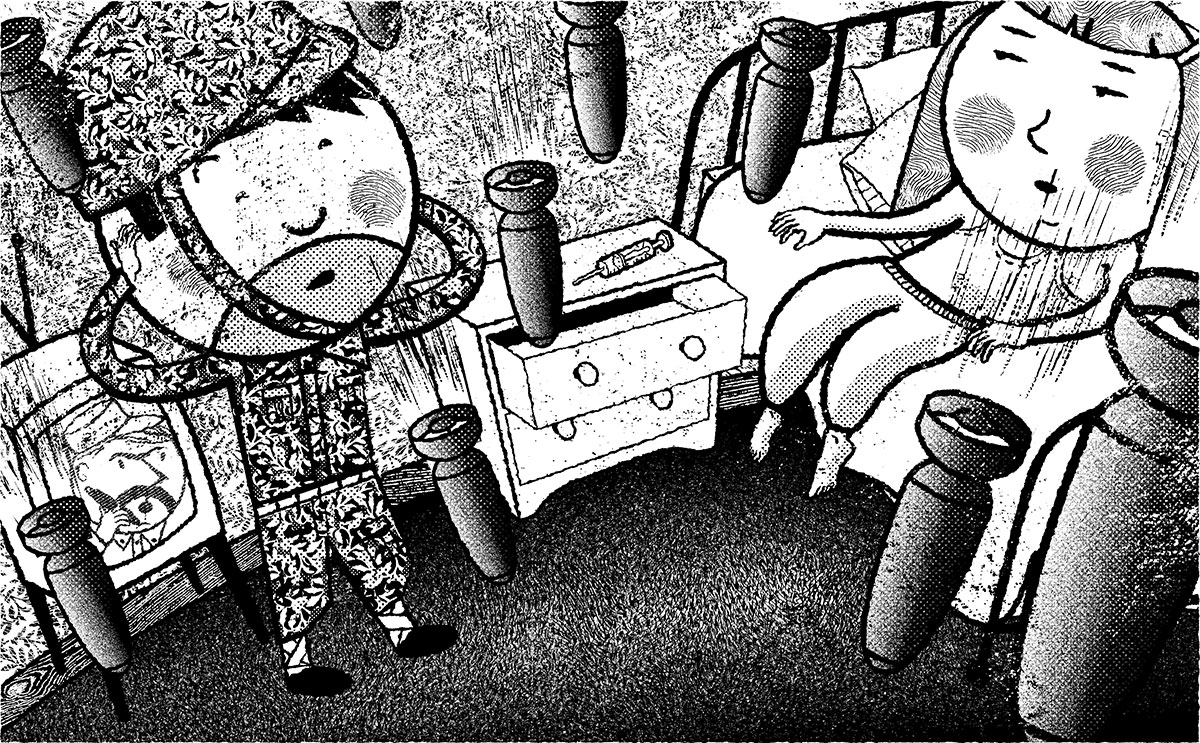

I walk across the stained beige carpet to the bed. The man on the TV yaps about Cuba. He smokes a fat cigar. I light a cigarette and reach into the night-table drawer. Remove the blue velvet bag, unwrap it, and arrange the apparatus before me. Ever since I was a child, needles haven’t frightened me. The nurses would say, just look away. The blood would flood into the tube, my eyes widened in amazement. There it was—my blood bursting into the vial like scarlet rapids. I’d yip with excitement. The nurses would look at me in disgust. I think it was disgust. To think it flows beneath my skin like a river and I never feel it, running and running and running without a sound.

I stick the needle in my neck. Blood turns to cream. Cool and thick, covering my entire body like strawberries. My head bobs, eyelids become weighty. My mouth dries. Wind gusts through the room. The window is shut. The bed sways. I am captain of my own ship.

I hear footsteps. You run across the room, cease to make noise, then clomp hard like you mean business. Reluctantly, I open my eyes. You’re in a soldier’s uniform. There has not been war here for years. You were never a soldier—nor was your father. You weren’t even born when the bombs blew your ancestry to pieces.

“What disguise is this? ” I ask. “What vision? ”

“I died. I will fight and die again,” you say.

“Who are you? ”

“The bombs drop and they drop and they drop,” you say.

“Nothing changes. I agree with you,” I say.

I look back out the window at the smoke-filled streets. Hear screaming babies, running feet, howls.

“What trick is this? ” I ask you. “What nightmare? ”

You kiss my cheek. A leaving soldier’s kiss. My stomach tightens, turns, a new sickness. I’m riddled with the dread of you going, never returning, falling bullet-ridden onto strange ground. I fall to my knees, grab your ankles. You drag me a few inches then shake me loose. You don’t turn around. I’m lying on a crusty motel-room floor in a time I never knew.

I call the lobby. The young Spanish woman answers the phone.

“I need a new room,” I tell her, “one with curtains. I need curtains now that I’m alone.”

“You’re alone now, señora? ” she says.

“Yes, I lost the only love I ever had.”

“Where did he go? ” she asks.

“To war,” I say.

“What war? ”

“Well, that’s the question. What war? ”

“I have the key, señora.”

“The key? ”

“To your new room, señora.”

“The one without windows? ”

“The one with curtains. You said you wanted curtains.”

“Oh, yes. Do you have one without a door? No door, so no one can leave me again? ”

Sheers don’t keep the light out. But I don’t think the voyeurs can see in. I don’t think they will return, maybe the occasional drifter. What is there for them to see now? I am faceless, bodiless. I just sit here and that’s not worth watching. No.

Are you there? Are you there? You are not. Were you ever really there? I go to the window, peek through the curtains. Are they there? They are not. Did they follow you? Your army. Was it you they watched? No, it was us. It was because it was us. Apart we are nothing, to them or to each other.

It must be true that heat rises. This room is too warm. The young Spanish woman moved me up and, though I’m afraid of heights, I feel like I’m making progress. I get up. Walk to the sink. In the mirror looms a grey replica of myself, hair stringy and painted to my scalp. I run the cold water, stick my wrists under it. My mother told me it’s a coolant. This is the desert, a murdering heat. I dry my arms. You warned me there’d be down times.

There’s a knock at the door.

“Your paper, señora, your milk,” says the young Spanish woman.

She knocks and she knocks. Can’t she tell by the old news piling up on the outside that I have no interest in the paper; by the sour milk, no interest in nurture? Yesterday’s news sits outside my room and she thinks today will be any different. Is she really so concerned, and yet not concerned enough to use her house key to come in and see what is what? It’s that almost-concern that is more hurtful than helpful—that apathy.

Are you there? Are you there? Were you ever there? Were you ever here? I believe that you were. I have scars to prove it. I’ll turn myself inside out and bare the damage. I’ll strip this window of its curtains and bare it all. I pace the room. The chair is losing a leg. The desk light burnt out days ago. The mice keep their distance. I flop down on the bed. What now? Let me see what I can pull from the ceiling. What cobweb remains?

I call the front desk.

“I need a new room.”

“What room? ” asks the young Spanish woman.

“What’s left? ”

“The honeymoon suite.”

“The honeymoon suite? ”

“Yes, but you haven’t paid for your other rooms. I can’t keep you. I cannot let you stay.”

“You cannot turn me loose. Where will I go? Not yet, soon, soon. He will bring money when he comes back and he will buy the whole motel, buy it all before he leaves again.”

“He will leave again? ” she says.

“They always leave again,” I say.

“When is he coming back? ”

“He’s on his way.”

“You’ve talked to him? ”

“Sort of.”

“Ah. I have the key.”

“The key!”

“To the suite, señora. Do you want champagne? You will want to celebrate, no? ”

“Yeah, two bottles of champagne. Two bottles and two glasses, yeah.”

The honeymoon suite is big, bright, distastefully decorated. It’s red, pink, and frilly. Smells of baby powder and aftershave. Who consummates marriage in such a room? Who sleeps here? Who can? I see something out of the corner of my eye. You are lying on the heart-shaped bed like a newborn child. You are two steps ahead. I knew you would come.

“Are you safe? ” I say. “Are you in pain? ”

“It is not safe here,” you whisper.

“No, it isn’t. I know,” I say. “Did you fight for this? ”

“What? “

“Did you lose? Did you win? Have you won? ”

“Won what? ”

“The war? ”

“There is no winning.”

“You lost? ”

“You can only lose.”

“You came here to tell me that? ”

I walk to the window. You raise your voice louder and louder.

“I’m talking to you!” you scream.

“No, you’re not. You are listening to yourself. Listening to your own voice, and why I do not know. Why you don’t get tired of your own excuses amazes me. You have been saying the same thing for years. Go to sleep. Sleep and be silent for both of us. Sleep and be silent, or come up with something new. Where did you go? ”

“Go? ”

“When you left. Where was it you went? Did you not learn anything there? ”

“I didn’t go anywhere.”

“You left. Left me alone.”

“I was here.”

“But I was alone.”

You sit on the edge of the bed looking at me like I’m mad—like I am mad. You, feigning ignorance, suddenly amnesia-ridden. Have you forgotten the dramatic exit, the inexplicable leaving lines? All I had was the draft blowing through the closed window, across the room, straight through me, and out the door. Then back through the door, across the room, straight through me, and back out the window I didn’t want. In and out and in and out, draft after draft after draft. And you wonder what I’m talking about?

We stare at each other, then out the window. Your mouth drops. I grab my things and leave.

“I need a new room,” you tell the young Spanish woman behind the desk. “One with a new wife. Then I’ll need the old room back.”

“I thought you had a wife,” she says.

“She left.”

“Oh, when did she leave? ”

“Recently.”

The young Spanish woman snaps her gum.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “Here’s the key.”

“To? ”

“Your new room, señor.”

“Does it have a wife? ”

“No, señor, but it has a phone and a phone book. You can look one up.”

The phone rings. It’s you. You tell me you’re lost without me. You never leave your room, where do you get lost? Surely, not in your room. In your head? I watch it ring sometimes, the phone. I sit carefully on the three-legged chair and watch it ring. It stops, and sometimes I regret not picking it up, but I know it will ring again. Why you call is beyond me.

You tell me you speak to other women. I know it’s a big phone book, lots of women to get to know. And that you talk to God. I wonder how you talk to God. You can’t afford long distance.

I never see you, and my eyes long to, I must admit. I hear you and hear you and my ears are sick of you. My head hurts. You don’t ask to meet me. You don’t leave your room. You are satisfied where you are. I forget to ask why you call. Why do you call? I forget to ask myself why I answer. I’d draw the curtains but there are no windows here.

The phone rings. You tell me you met another woman. She’s young, and it won’t lead to anything, but you had to keep in with the young to keep up with what’s going on out there. You said she calls and she calls.

“Why are you telling me this? ” I ask.

“It’s news,” you say.

“It’s nothing,” I say.

“Exactly.”

“It’s something to me. It’s nothing in general. News would be you’ve turned the corner. Had an epiphany. Can’t live without me. Made plans for the future and I figure prominently in them. You’ve seen the light and you are coming to pick me up by it.”

“I can’t help you,” you say. “Atlas carried the world on his shoulders, but there are no more men like that.”

The phone disappears

The young Spanish woman warns me that if I throw one more phone down the hole I made in the floor they will throw me out on the street. I say, if they keep replacing the phones, I’ll throw myself down the hole I made in the floor and I’ll be harder to pick up. I pace the room. There are traces of intruders, hairs, a merciless scent of sweat. How they get in, I don’t know. I thought I locked everything up from the inside. Still, they manage to weasel their way in. I want no one here. And that phone, that link. That one vein I cannot puncture and drain dry. An umbilical cord that links me to you. The telephone cord. A telephone cord.

I call you. Another man answers.

“He isn’t here,” he says.

“What do you mean, he isn’t here? Who are you? ”

“I live here,” he says.

“You didn’t live there yesterday.”

“And that means what? ”

“That means that you only live there as of today, and that someone else lived there yesterday, and you probably know who, and why he is not there now.”

“No, I don’t know. The room was empty.”

“Except for a phone? ”

“Yes.”

“And a phone book? ”

“I don’t know.”

“Look.”

“No.”

“No, what? ”

“No, there is nothing else.”

“Did you look everywhere? ”

“There is nowhere else to look.”

“I see.”

The young Spanish woman cleans the lobby windows. Her jeans grip her hips awkwardly. Etched into her lower back is a fire-breathing dragon. I gasp, startling her. She shifts her hips, folds her arms across her chest, and hisses at me. I shuffle back to my room and peer out the window. My hands ache. The skin is cracked, rubbed to the bone.

You walk through the door with two coffees. A brown paper bag protrudes from the pocket of your red velvet blazer. You’re unshaven, hair in clumps. Your skin’s ruddy but not like sunburn. You tell me it’s a beautiful morning. The sun’s on fire, not a cloud in the sky. The off-licence on the corner is closed. You had to walk over to Harvey’s convenience, then meet Frank for the goods. I throw myself on the bed. You stroke my head, tell me I’m sweating.

Your face changes, eyes roll and widen. You stand up, turn in circles, ask why the bed covers and clothes are strewn across the room, the phone ripped from the wall, desk and chair upturned. You storm over to the window.

“What the hell have you done to the curtains? ” you say. “I leave you alone for five fucking minutes and this is what happens? ”