Helène finishes the second sleeve of the sweater and thinks of her grandson. After counting the rows of the cuff out loud en français, she takes hold of it with both hands, making sure the knit two, purl two rib pattern is even. She casts off the final row with black yarn, knowing it’s Nikky’s favourite colour. The deep charcoal grey of the rest of the sweater will match his eyes. With aching, shaky hands progress is slow, but she has time. Aside from her neighbour Charles, no one—not even her son, Geoff, and his ex-wife, Annette—has come to visit in the past two weeks. Not since Nikky went away on his travels. Helène fills her long afternoons instead with the rhythmic conflation of knit and purl, sips of tea, and her circular thoughts. She frequently thinks of having a drink—a happy hour Scotch and soda, a glass of evening wine, a shot of brandy for her tea—but it’s Nikky she thinks about most often. Twisting yarn and the clack-clack of her needles ease her worries like good conversation. Helène is certain Nikky’s sweater will be ready for him by the time he comes back.

Helène often thinks of the day she saw the first circle of stones. After it became clear Geoff had forgotten to bring her groceries, Helène had ventured out for a rare stroll on her own through the coastal mist. Slowly rounding the corner of the sea walk where the path widens into Rotary Beach Park, she noticed a circle of white stones at the foot of an aged evergreen. Inside the circle, a toy truck decorated with glitter glue, gaudy plastic flowers, and a glass Mason jar of messages from family and friends nestled on a tidy patch of bark mulch. When she saw the name “Mike the Trucker” scrawled on the toy rig she made a tut-tut sound, remembering reading about the unfortunate fellow in the newspaper. Mike was on the side of the road trying to fix a blown tire when a young man speeding to make the Vancouver ferry hit him, dragging him under his sports car for hundreds of metres. The young man kept driving. Mike’s crumpled body rolled into a ditch, and still, he kept driving. It made Helène think about how many kids grow up without learning the right kinds of things in life, which made her think of Geoff. Helène believed that somehow, as an elementary school vice-principal, charged with the responsibility of a school full of children, she had failed her own son.

It began to get dark, and Helène walked home in the early winter twilight, taking one slow step at a time so she wouldn’t trip or fall. The bright lights of her oceanview condominium were a beacon, and coming home to the crisp and immaculate lobby, she took a deep breath of its fresh laundry smell. Picking up the weekly flyers from the stack on the oak newspaper table, she frowned at her mist-melted silver curls in the antique mirror above. Then, glancing up the curve of the grand, milk-coloured stairway on her way to the elevator, she began to shake violently at the sight of a pair of brown Florsheims. Charles was lying on the carpeted steps in his suit, his briefcase upturned beside him, files scattered. Stumbling down the hall, Helène found she could barely lift her hands and make fists to bang on the superintendent’s door for help. Later, standing over Charles’ inert body, waiting for the ambulance, she would have lost her balance entirely had it not been for her ugly but solid orthopedic shoes.

The blaring ambulance sirens were followed by a week of hushed hallway whispers and stares. Charles returned after a night in hospital and avoided eye contact, keeping to himself, even after his Coast Tyee Insurance office published his retirement notice in the Courier-Islander. After watching and waiting for her moment to find out if he was all right, Helène finally cornered him in the mailroom.

“Congratulations on your retirement, Charles,” she said, enunciating each vowel as though making an announcement over her school’s P.A. system. “We’ll be seeing more of you around here, I expect.” And, as a rare patch of sun shone through the lobby windows and glinted off silver mailboxes to make patterns on the carpet, Charles fiddled with his new cane and told her about his diabetes, as though admitting it for the first time.

“I had a diabetic attack last week,” he said, in his slow, steady business voice.

Staring past Helène in the mailbox gleam, he added, “Thank you for helping me. I’ve had to make some changes, and now the doctor says I have to start walking every day to control this condition. But no hills and no stairs.”

He looked at her then, lowering his chin and casting his eyes down to meet hers, his white eyebrows pinched. “Sounds boring,” he said.

The fact Charles said exactly what he was thinking reminded Helène of her grandson.

“I’ll walk with you,” she said. “I start to fidget when I stay inside too much.”

She did not add that her son had taken her driver’s licence away because of her advancing Parkinson’s, or that she felt housebound as a result.

Charles and Helène began meeting downstairs in the lobby at ten every morning to go for a stroll. They chose the Seawalk as their route, a long path following the Georgia Strait from one end of town to the other where the sound of the tide somehow always drowned out the buzzing traffic. They rarely talked. The view of the Pacific, the mainland mountains, the bobbing fishing boats, and the occasional sleek cruise ship seemed enough.

A few months later, Helène’s Nikky, on reading break from his studies at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, in Vancouver, came to town by bus and chose to stay with her. He called her on his cell from the bus station to tell her.

“Mom’s got a dog show this weekend, and when Dad saw me with metal in my face, he turned around and got back into his truck,” Nikky said. “Can I stay with you? ”

“Of course, dear,” Helène said, feeling a quivery thrill to hear Nikky’s young man’s voice. When Nikky arrived at the door she gave him a big hug, pressing a ten-dollar bill into his hand to pay for his cab ride from the bus station. Looking up into his face, she wondered how a little piece of silver in his eyebrow and another in his nose could be any worse than the dragon tattoo his dad came home with from a logging camp up north in the seventies. Back then she’d been upset at her son, but her ex-husband, Tibor, had been furious. Remembering, she noted the circularity of the moment, realizing the cycles that span generations were something only grandparents could see.

On Nikky’s first full day back in town, Helène made a big breakfast of toast, scrambled eggs, and beer. Nikky was quiet, and every time Helène thought of a question she wanted to ask him about school, his apartment, or whether he had a girlfriend, she stopped herself and instead offered him more blueberry jam. When his plate was finally empty, Helène stood up from her chair at the head of the dining table.

“Now, dear,” she said, looking at him over the rims of her glasses. “Would you like to go for a walk with my neighbour Charles and myself? ”

She didn’t wait for his muffled reply before reaching into the metal stand by the door and handing him her spare umbrella—she knew the beer would help convince him—and once downstairs, they started out like every other day, by popping their umbrellas open. Even though the mist still got in everywhere, it was Helène’s ritual.

“Those are some sturdy-looking boots,” Charles said, eyeing Nikky’s tall black military-style steel toes. Helène was surprised when he didn’t say anything about the pointed spikes sticking out of Nikky’s jacket.

“Thanks,” Nikky said, putting his head down, flipping his collar up over shrugged shoulders.

Charles began walking on one side of Helène, Nikky on the other, neither saying anything else. She knew the three of them were quite a sight walking down the path: an elderly man in a ball cap, a shaky old lady in a proper cashmere twin-set and matching silver overcoat, and tall Nikky, clad in black from head to toe, like a cartoon villain.

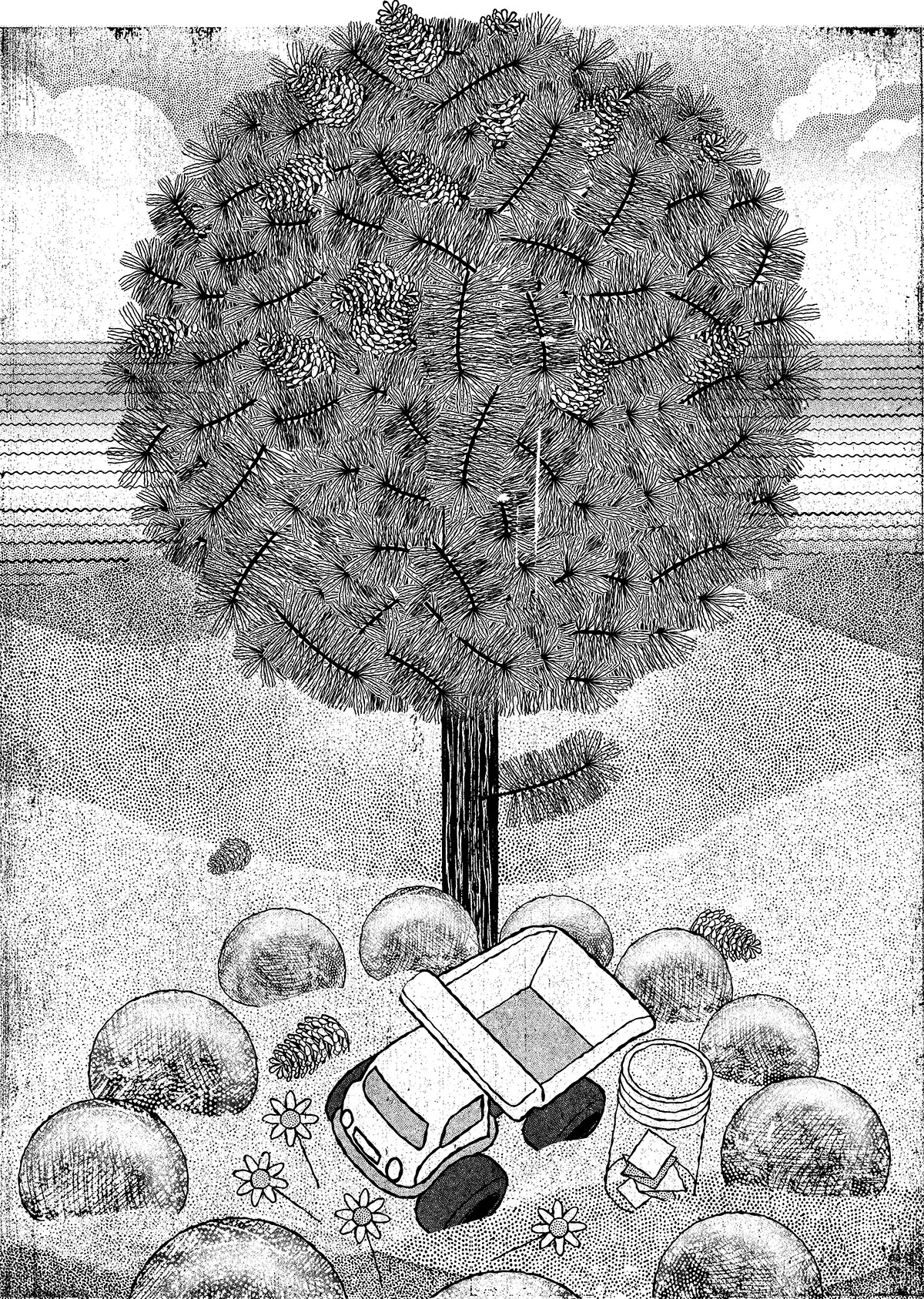

At the beach park, Helène stopped and pointed a gloved hand at a new circle. Clean beach rocks surrounded a miniature organ, a framed photo, and a small, freshly planted tree. A dozen small stones clustered in the middle were each painted with a black musical note. A card-sized plaque read: “In memory of mrs. marilynne manson, wife, mother, grandmother, organist.”

“It should be the other way around,” said Helène. “Organist first.” But both Nikky and Charles were chuckling, and the fact they both seemed to get a joke Helène didn’t understand made them laugh even harder.

Charles finally sat down on a tree stump.

“Marilyn Manson is the name of a goth rock musician,” Charles explained. “I saw him on MuchMusic the other day. Quite the sight.”

“I can’t believe this old dude got the joke,” Nikky said, looking approvingly at Charles. “I can’t wait to LiveJournal my friends.”

After their walk, Helène, emboldened in the presence of her grandson, invited Charles in for a cup of coffee. She served Charles black coffee first, on account of his diabetes, then slipped a shot of Baileys into the china cups for Nikky and herself. She efficiently whisked up a batter in the kitchen, and then reappeared a dozen minutes later with fresh blueberry scones piled high on her Limoges platter.

Nikky stayed for a week, during which time Charles and Nikky spent coffee time talking about music videos and horror movies, which they both seemed to know a lot about. Helène, who also watched a great deal of TV, but who was partial only to BBC mysteries and Coronation Street reruns, was content to listen. Nikky was good company for her—together they sipped fine liqueurs and tried to decide which one they liked best, arranging the bottles on the table from least to most sweet. One afternoon, as Helène was taking Nikky’s new measurements to write in the Growing Up scrapbook she’d kept for him since he was a baby, he told her about his girlfriend, Jennifer.

“She’s amazing, Grandma,” he said, and as Helène measured up his shoulder for his arm length she noticed goosebumps on his skin. Embarrassed, Nikky changed the subject.

“I wish you could see some of my new paintings, Gran,” he said. “The stuff I’m doing now is way better than what I was doing in high school.”

The morning Nikky left to go back to Vancouver felt worse for Helène than the last day of school before summer vacation. Helène had tucked a bottle of crème de cacao in Nikky’s suitcase and told him to bring his girlfriend to meet her at the end of term. Later, in the parking lot, Helène thought she saw Charles slip a twenty-dollar bill into Nikky’s palm like a proper grandfather would do. And then she and Charles stepped back onto the curb and waved as the cab sped away. She stared at Charles for a moment, knowing it probably wouldn’t have occurred to her ex-husband to even pat Nikky on the back or shake his hand.

For weeks after that, the days alternated between the greys of rain and cloud typical of northern Vancouver Island. Although Charles and Helène continued to visit after their walks for what they called B. & B.—beverage and biscuit—they began to run out of things to discuss.

The third circle of stones was a vision of colour in the rain-darkened dirt. As Charles and Helène approached they saw beach rocks painted primary-school blue. The rocks encircled a plastic spaghetti container full of crayon drawings, two Tonka trucks, and a tiny ceramic handprint labelled “noah, age 5.” Helène recognized the perfect, rounded block letters of a Grade 1 teacher. Thinking of what it was like to be a young parent, she knew the boy’s mother and father wouldn’t have been able to lift stone after stone, put the memory of their son in the middle, leave it behind. Charles stared at the child’s photo, which, though laminated, would eventually fade in the sun or melt in the rain. Noah had big ears, messy, overlong hair and a missing incisor. His skin looked orange in that way school portraits make all children look like carrots.

Helène cleared the catch in her throat with a gentle cough and sat down on the park bench. Dampness seeped through her coat and slacks to her skin, chilling all the way to her aching bones.

Charles seemed nonplussed. Undignified with its toys and bright, sloppy splotches of glitter glue, the circle appeared as though made by “noah, age 5,” but Helène liked the childish sentiments. They reminded her of her former life, when she worked at Captain James Cook Elementary School.

“I give the Tonka trucks two months before someone steals them,” Charles said, banging his cane on the cedar chip path.

Helène watched Charles yank on the brim of his cap, zip and rezip his navy windbreaker. He’d lost weight from their walks and his overlarge navy blue slacks rode too low and hung over the laces of his black leather running shoes. He looked like an old kid in school uniform. With white, thinning hair.

“Oh, I don’t know. Maybe they’ll leave them,” she said surveying the contents of the first two circles. “The others are fine.”

Charles turned pensive and they walked back to the condo in a silence Helène couldn’t find a way to breach. She stole a glance at him as he stared up at the L.C.D. light in the elevator, waiting for it to be the third floor. His expression, after years of negotiating insurance claims, was impenetrable.

“What would you like to drink today, Charles? ” she said, opening her door with a jangle of keys.

“Thank you, but I have some business to attend to today, Helène,” Charles replied, taking his own keys from his pocket.

Helène entered her apartment and tried to will her hands to stop shaking. When she was finally able to wriggle out of her coat, she gasped. The wet spot from sitting on the bench was still visible. Soiled like a small child’s coat. She made tut-tut sounds, knowing Charles must have seen it. After struggling to hang her coat on the hook, she stood alone in the dim entryway and hung her head. She cleared her throat and then counted her small shaky steps to the kitchen out loud in French, like she used to do with her students to take their minds off upsetting things. Un, deux, trois, quatre, cinq, six, sept. Picking up an open bottle of sherry, she drank two small crystal glasses of it and threw the freshly baked, Saran-wrapped cheese biscuits in the trash. She shuffled to the living room and turned on the television, but couldn’t settle, even nestled in the warm pocket of her big chair with her crocheted afghan over her knees.

“Tut-tut,” she said to herself. “Tut-tut.”

That afternoon, Helène busied herself by organizing her liquor cabinets, lining the bottles up and turning the labels out. Her guest bar was the lower shelf of her large antique china cabinet, but she kept her private bottles in a former safe in the master bedroom, behind a large, gaudy macramé frog wall-hanging she bought at a craft bazaar years ago. She’d always admired his gaping, hungry mouth. It made more sense to her than hanging a dream catcher.

There was a soft knock at the door and Helène returned the frog to its place on the wall and stepped out into the hall to see Annette striding in, holding up two bottles of ice wine from the liquor store she worked at. When her Geoff and Annette divorced, a week after Nikky graduated from high school, Helène had insisted that Annette keep her condo key. Like her own, Geoff and Annette’s marriage had always been tenuous. But Annette was as generous and kind as the friends Helène remembered fondly from where she grew up in Montreal, and she didn’t want to lose touch with her.

Annette retrieved the bottle opener from the kitchen and opened both wines for Helène, and they sat at the dining table while Annette fiddled with the sleeves of her oversized sweatshirt and talked about her union’s complicated contract negotiations at work. Helène listened until Annette stood to pour more wine into their glasses.

“And how’s Nikky, dear? ” Helène blurted out between sips.

“Well,” Annette said, her fatigue-narrowed eyes widening. “It sounds like the girlfriend left and he’s upset, but that’s young love, eh, Helène? ”

“Oh, such a shame,” Helène demurred, “He really liked her. I wanted to meet that girl.”

Annette leaned back in her chair and gazed out the picture window at the sea. “I’m hoping Nikky will use the experience to further his art,” she said. “He’s smart, you know, like all those other romantic artist types.”

Helène paused to straighten the coaster under her glass, but her tremoring hands nearly knocked it over. “I would like to see some of his newer art soon,” she said, placing her hands on her lap.

When Nikky was in high school he’d painted a cityscape that had reminded her of Montreal, even though he’d never been there. Annette’s favourite painting was one he did of the trees around her house, but Helène found that painting oppressive. Something in the way he’d painted the cluster of tall, stalwart evergreens made them look like a small, green army.

Helène fretted privately about Nikky while making a niçoise salad for Annette in the kitchen. Concentrating on chopping lettuce, she didn’t hear the door open again, or the heavy footsteps in the hall. She didn’t see the exchange of dirty looks passed across the table between Geoff and Annette. But she did hear the loud clunk of Annette’s chair hitting the wall as she hurried to get up out of her seat, avoid a confrontation.

“Bye, Helène, I’ve got to be going back to work now,” Annette said, leaning into the kitchen and patting Helène on the shoulder.

“Well…,” Helène said. “Well, won’t you please take this salad with you in a nice container? You should eat lunch, dear.”

Geoff loomed like a big, immobile tree transplanted into the dining room.

“No, no, you have that for yourself, Helène,” said Annette, briskly stepping around Geoff and heading toward the door.

“Ma,” Geoff said, his voice booming in comparison to the ticking of the clock, the whir and hum of the condo heating. “Aren’t you ready to go? ”

“I’ll be ready in a minute dear,” Helène said, hurriedly placing the salad into a bowl and shoving it into the well-stocked fridge before she too ducked around Geoff and into the hall. In her bedroom with the door closed, she freshened up with a little face powder, lipstick and a spritz of Coco Chanel, taking a couple of deep breaths before she opened the door again. It wasn’t that she had forgotten Geoff was coming—it was that she’d forgotten it was Wednesday. She looked at the nature calendar tacked to the back of her door and crossed out Tuesday with the pencil she usually kept behind her ear. Then, walking into the hall, she focused on straightening her back, making herself as tall as possible—not that it gave her much authority.

Geoff looked at her, his bulging eyes disconcertingly similar to his father’s. He stepped toward his mother, leaned down, and put his face close enough to hers that she could feel the grease of his hair, smell his cheap aftershave. His chewing gum and nicotine mouth.

“Ma, you’re not supposed to be drinking,” he said loudly, shaking her shoulder with his root-claw hand.

“Annette brought a lovely ice wine for me to try.” Helène said, taking a step back, leaning on the wall for support.

“Christ! I told her to quit that,” he shouted—adding “that bitch” under his breath, as though Helène couldn’t hear.

“Well, dear, her visits are enjoyable,” she said, “And she lets me know how Nikky’s doing.”

Geoff looked away. “Let’s go,” he said, walking toward the door. Trying to keep up, Helène barely had enough time to put her coat on, straighten her collar, and lock the door. She was afraid of Geoff leaving without her as he had done before. Her hands shook and she couldn’t catch her breath. When she got to the elevator Geoff had his finger pressed on the door-open button, but he looked away as his mother stepped in. As he stared up at the floor numbers changing, Helène had trois, deux, un seconds to feel the back of her coat. She was relieved to discover it had dried.

In the parking lot Geoff opened the passenger door of his truck and pulled out a small plastic step Helène had purchased so she could climb in. He revved the engine while the radio blared the same seventies rock he’d listened to as a teen. The music his father couldn’t stand and Helène put up with—until the day she came home from shopping after school and Geoff wasn’t there. Tibor had kicked him out for smoking pot—a hasty, stupid thing—considering Geoff was only fifteen and a half. Helène stopped talking to Tibor after that. Geoff left for the logging camp and she didn’t see him again until several years later.

All the way to the doctor’s office, Helène thought about how her son left home far too young. She had wanted to teach him a few more things about gentlemanly behaviour. She would have liked to see him wearing crisp white shirts. He could have been a businessman. Instead, he was a logger–turned– general contractor—a house builder who lived alone in a small, musty-smelling, rented apartment. He was just like his father, and the allure of brawn, as Annette and Helène both discovered, doesn’t last.

Geoff stopped off at the door of the doctor’s office, waited for Helène to get out and shut the door, and sped away in his truck without looking back. But the doctor saw her right away for her checkup, and even after she got her prescription refilled at the pharmacy next door, she waited an hour and a half for Geoff to return and take her home. She’d already read all the magazines in the doctor’s waiting room, and Cindy, the receptionist, kept looking at her with sympathy in her eyes.

“She looks young enough to have been one of my students, years ago,” Helène thought to herself, remembering the days when children were afraid of her and teachers and parents respected her authority. She stared at the low pile carpet, trying to decide whether it was pink flecked with grey or grey flecked with pink. When she got up to use the powder room she chose the one with the oversized handicapped sign on the door, where there were cold metal bars to hang on to. When she looked into the bathroom mirror she thought of Nikky. He had her eyes. Voluminous pools of grey determination surrounded by dark rings of self-doubt. Helène looked away and busied herself with washing her hands, waiting for the tepid water to turn hot.

By the time Geoff returned it was raining again and Helène had forgotten her umbrella at home. During the drive back she fretted about what the rain would do to her hair set. It wouldn’t do to arrive home and have her neighbours see her looking as bedraggled as her son. She didn’t want Charles to see her that way. But when she walked into the condo lobby, shaking rain off her coat, she looked up into the oversized, gold-framed mirror and saw her silver curls still bouncing.

Back upstairs, Helène sipped from another glass of ice wine while she made a batch of blueberry scones for the morning. She paced back and forth in the living room while waiting for the oven timer to ring, thinking about Nikky and then about Charles. The timer bleated its staccato beep and she put the scones on a trivet to cool, checking and rechecking to make sure she’d turned the oven off. She flipped the pages in a mystery novel, realizing she was clever enough to have already figured out whodunit, but not enough to know whether her neighbour wanted to see her.

Helène spent the evening in front of the television, the rest of the ice wine her companion. Waking up, she felt something prickling her face. Carpet. The colour of slate. The same shade as the dull morning light streaming through the windows. Wobbly, she pushed herself up to her feet, using her chair for support, and stepped over to the windows to look at the tufts of morning fog coming off the water, rolling up like the spasms in her stomach. Near-invisible cars inched along the highway, cutting through interminable grey with their headlights. She looked around the room and saw that the TV was still on, broadcasting an exercise show. The silent grandfather clock displayed 6 A.M. She sensed an odour. Moving her hand lowly to the seat of her slacks she felt a large damp spot.

In the bathroom, Helène kept the door closed and the shower on long after she finished bathing so she could stand in the steam to warm up, give her skin a refreshed glow. “Je m’excuse,” she whispered, like she might have done as an ashamed child. She knew she was too old for a hangover, and that her body had betrayed her. She struggled out of the shower, wrapped herself in a pink towel, and put her pants to soak in the sink with a capful of Woolite. Later, she sat in her robe and slippers at the dining table, sipping black coffee and watching the fog slowly dissipate, along with her headache. Around seven the tide began to change, the waves becoming agitated. Helène thought of the too many ways she had already lost control, and she still didn’t know if Charles would want to see her.

Later, after getting dressed in her bedroom, she put her ear up against the wallpaper above her nightstand. She could hear a clock radio tuned to the CBC and realized that if she knocked on the wall Charles would hear her. She sat on the bed and stared into her closet at the old cedar trunk where she stored balls of yarn and knitting needles. Shakily standing and opening it, she discovered she had what looked like enough charcoal grey yarn to make a sweater for Nikky, and it was already wound. She selected a pair of size eight needles from her crocheted needle holder and returned to the living room. Seated in her big chair, she began to knit, counting the stitches out loud as she cast them on. “Un, deux, trois, quatre, cinq…” Without a few steadying drinks in her, each stitch was a struggle, and as she knit row after row, her fingers began to ache.

At five minutes to ten she got her keys from her handbag, dropped them into the pocket of her overcoat, took her umbrella from its stand, and headed to the elevator. She was shaking a lot. Her medicine wasn’t working. But when she stepped out of the elevator, Charles was already waiting for her at the lobby door.

“Good morning, Charles,” she said, popping her umbrella as she exited the door he held open for her.

“Good morning, Helène,” he said, unfurling his.

They walked at their usual slow pace through the mist. Helène caught Charles looking at her and returned his gaze, lobbying it back like a badminton shuttlecock. She had been good at that game in her day.

“Feeling all right? ” he inquired.

“Oh yes,” Helène said, “Just fine. And you? ”

“Well, thanks,” he replied.

They walked for a few more minutes, stepping to the side to allow a jogger and his big brown dog to dash past. Helène felt Charles looking at her. He stopped. So did she. He reached his hand toward her face and touched her cheek so softly, the sensation got caught in a gust of wind and twirled all around her. For a moment the weather held her steady.

“Helène,” he said.

She wanted to touch his hand, but he would have felt her shaking.

“I don’t want to be like other old people,” she said.

Charles let his hand fall to his side.

“We don’t complain, though,” he said. “Like other old people and their incessant blather about their aches and pains.”

Helène nodded and they started walking again.

“You helped me, Helène,” Charles said. “I can help you.”

The words were like someone taking Helène’s hand, the way she used to take small children’s hands in hers and lead their hesitant, trembling bodies to their classrooms.

When they got to the park, Charles took a long sheet of plastic out of his pocket, spread it out to cover the wet bench for the two of them, and sat down. He banged his cane on the carpet of grass at his feet, and even though she looked at them every day, Helène visited the circles. She saw how each plastic flower was fading and tried to remember its original colour. She observed the weathering wood of the picture frames. The Mason message jar had been knocked over and the Tonka trucks were covered in dirt, possibly disturbed by a cat or a raccoon. She stepped back and counted. Un, deux trois, knowing there would be more.

“Helène,” Charles said when she returned and perched on the bench beside him. “When I had a house with my wife, I hired neighbour kids to come over and mow the lawn and trim the hedges. And after Meredith passed on, I moved into the condo and hired a housekeeper who looks after everything.” Charles took a handkerchief out of his pocket and dabbed the sea mist from his forehead and nose.

“I’m not a nature person. I’m a numbers man, so I might not know how to do this. And you’re an elegant French lady,” he said, “so I can’t expect you to dig in the dirt.”

“Certainly not,” Helène concurred.

“But I believe somebody has to start looking after these memorials,” he said. “I think we should do it.”

Helène looked at Charles. His glasses were covered in mist, but she could still see his grey eyes.

“Everything is deteriorating, Helène,” he said with a thud of his cane.

“It’s inevitable,” she said, remembering how dashing Charles used to look around town in his suit. He was a man you’d notice walking into a bank or restaurant. She realized how difficult it must have been for him to retire, become invisible. Helène knew—when an elementary school vice-principal walks into a room, people look up in attention. People see a silver-haired woman with shaky hands and think, “I hope she doesn’t fall down our stairs.”

“Let’s make it anonymous,” she said.

“Our secret? ”

“Of course.”

Walking back to the condo, the only thing that would have made the moment more perfect in Helène’s view would have been if Nikky were there, the two of them flanking her. But she thought of him as she walked. And Charles. Her two good men.

Outside her door, Helène dug around in her pocket for her keys.

“Would you like to come to my place for B. & B. today, Helène? ” Charles asked, gently taking her arm. “For a change of scenery? ”

It was Helène’s first time in Charles’ place. She admired his large wooden bookcases, his antique globe, and noted that the floor plan was identical to hers.

“Now,” said Charles, fumbling in the kitchen, “I don’t have anything fancy, and I’m sorry to say I drained my liquor cabinet of all of its sugary temptations, but I can make you a cup of tea with honey and lemon.”

“That sounds lovely,” Helène said. And, looking over at Charles, she tried not to notice the long row of medications on the counter behind him. She sat down at the fine oak dining table and placed her hands under her knees to prevent them from shaking.