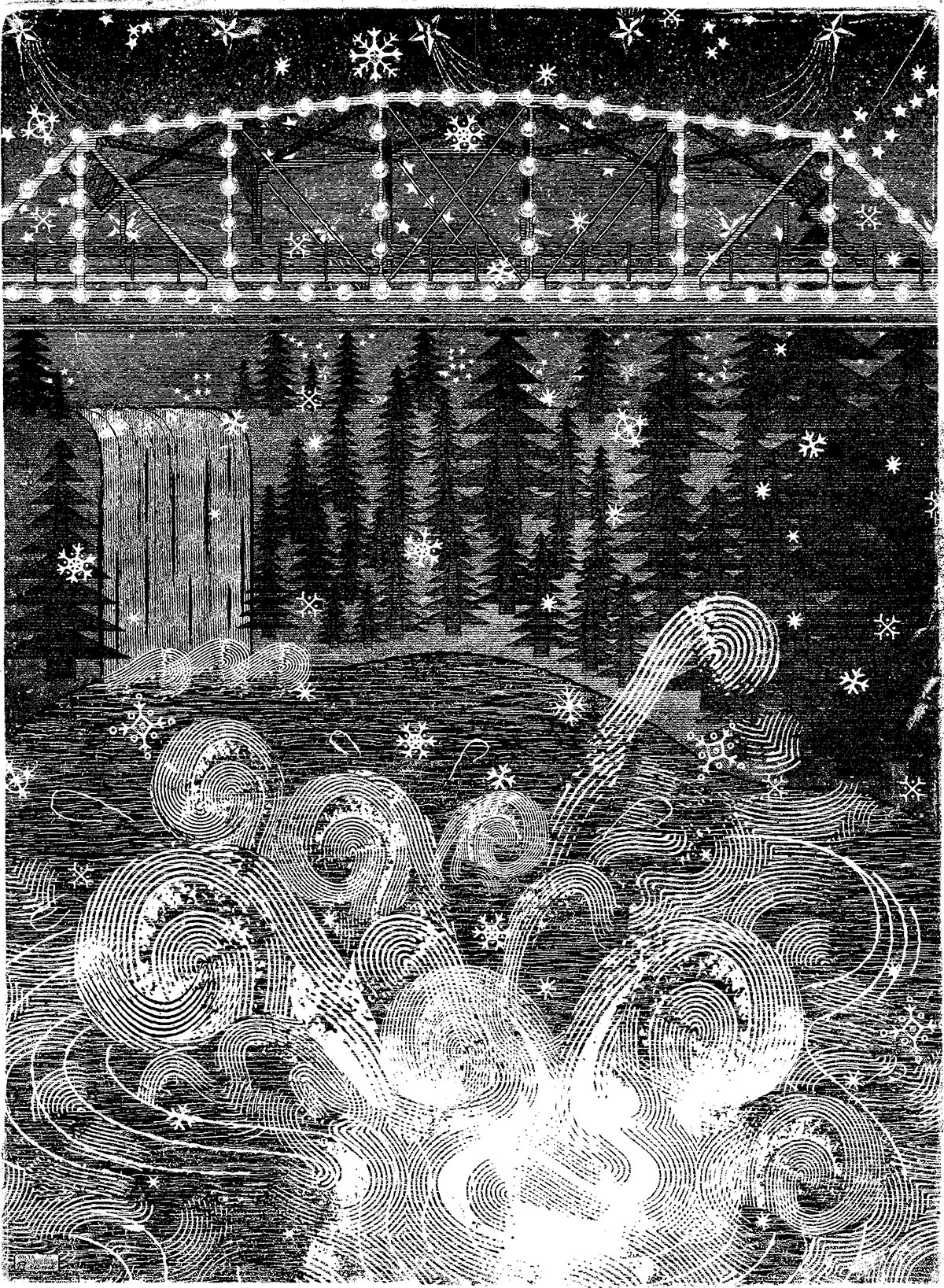

Crying. That was the last thing George heard before he left the house. Had he shut the door behind him? He couldn’t remember. He felt nothing, not even the cold, though he’d left without a coat. Fat snowflakes stuck to his sweater and hair as he moved toward the centre of town, to the bridge and the falls.

“Merry Christmas, Mr. Bayliss.”

One of the Cole children doing something on the lawn. Snowman?

“You all right, Mr. Bayliss?”

George kept walking. He kept walking until he made the Edgewater and his favourite bar stool.

“Hey, George. What are you doing in here on Christmas Eve?”

“The usual, please.”

Simon scooped some ice into a glass and poured the Bushmills. “Everything O.K.?”

“Make it a double.”

“Hmm. That doesn’t sound so good. On the tab?”

“No.” George fished out his last twenty and dropped it on the bar. “That’s fine,” he said, moving away from Simon’s concerned and inquiring gaze to a table in the corner where he chugged the whiskey in three swallows. No burn in the throat. And he was as sober as before. He lit a match and held his hand over the flame. He thought about Marianne’s tears. He thought about the kids. “God,” he said in his mind, “I’m not a praying man, but if you’re up there and you can hear me . . . show me the way. I’m at the end of my rope.”

George waited. He scanned the bar. The Ryan twins were playing darts. A group of teens was playing pool. Everyone else seemed to be involved in the electronic trivia game lighting up the monitors suspended from the ceiling. There was music from the jukebox. A rock ’n’ roll version of “Frosty the Snow Man.” Andrea, the good waitress, stopped at his table.

“Hey, George. Merry Christmas.” She placed his empty glass on her tray. “Listen, thanks again for putting in the word with Simon. I don’t how I would’ve made it through the holidays without this job. You want another? I’m buying.”

Before he could answer, the heavily loaded tray slipped from Andrea’s hand and spilled onto the table and George.

“Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry!” She plucked a glass and an ashtray from his lap but hesitated before brushing away ice cubes and cigarette butts. “Sorry about that. Oh jeez!”

“It’s O.K.,” George said. “Don’t worry about it.”

“Sorry!”

George got up and left the bar. He walked down the street and across the bridge to the cliff on the north bank of the river, just below the falls. He moved close to the edge and the swirling black water. He stared hard at that swirling black water.

He jumped.

Strangely, he felt nothing as he entered the river, except perhaps a momentary flash of relief. But seconds later, as his body surfaced, he was seized by a blast of intolerable pain, one that seemed to trigger in each of his cells an overpowering desire to live. George sucked for air, but his lungs felt as if they had been squeezed shut. Myriad confused images of Marianne, the kids, his brother, and his mother cut through his brain as he thrashed in the water, determined to survive. Pure will propelled him toward the edge, and just when he knew he couldn’t last another minute in the freeze, his feet found bottom.

As George struggled onto the embankment, a stranger appeared out of nowhere—an old man with ruddy cheeks, twinkling eyes, and charmingly disheveled white hair. He kicked George back into the river.

“Help!” George screamed. “Please!”

“I thought you wanted to die?” the man said.

“No. I want to live!” George hoisted himself half out of the water.

The man smiled benevolently and kicked him back in. “Just relax,” he said.

“Please! My wife—my children need me!”

The man chuckled. “Trust me, George, with an eight-hundred-thousand-dollar life-insurance policy, you’re worth more to them dead than alive.”

“How do you know that? Who are you?”

“Somebody’s dying to meet me,” he said to the sky, with an aw-shucks chuckle. The man crouched and extended his hand for a shake. “Terrance Angel II. Very pleased to make your acquaintance.”

George grabbed his arm and held on with every iota of remaining strength. If he was going down, this lunatic was going with him.

“Oh, Georgie,” the man said, yanking him onto the bank with one effortless pull. “Why bother?”

George was shivering too violently to speak. Even after Terrance removed his overcoat and draped it around him, he shook and shook. He was disoriented, confused. He could not connect the image of the smiling codger—now wearing old-fashioned long johns and rubber boots—with the sadistic behaviour recently displayed. It was like getting punched in the throat by someone’s granny at a Sunday-school picnic. Terrance sighed and put his hands on George’s shoulders. He felt a tremendous warmth surge through him then, and in less than a minute his shaking had subsided, the pain had flown, and his clothes, inexplicably, had dried.

“There now,” Terrance said, helping him to his feet. “Are you sure you don’t want to hop back in?” He gestured to the river and patted George on the bum.

“Of course I’m sure. What the—”

“Because if you’re worried about Marianne and little Matthew and Zoey, I can assure you they’ll be just fine on their own.”

“Oh really.”

“Indubitably.”

“Look,” George said, doffing the madman’s coat, “if you knew anything about me you would know that my wife and children love and depend on me.”

“Is that right?”

“As a matter of fact, quite a few people in this town love and depend on me.”

“Really?”

“Oh, I’m not saying I’m the most important person in the world, but I’m a good man, an honest man, and I make a difference in people’s lives. I make a difference in this community.”

Terrance smiled gently. “Well, George, I think you may be exaggerating your impact just a tad. Not only would it not be the end of the world if you drowned yourself in the river tonight, it wouldn’t really matter much if you had never been born at all.”

George gasped at the coot’s audacity. “How dare you,” he sputtered.

“It’s true,” Terrance said. Then, looking heavenward, he asked, “May I?” A star twinkled as if in response. Terrance grinned and took George by the arm. “Come along,” he said.

“Don’t touch me! You’re crazy.”

“Crazy? Why, if I’m so crazy, how come your clothes are dry?”

George opened his mouth to answer, but no answer arrived.

“You’ve been given a great gift, George: a chance to see what life in Fenton Falls would be like without you.”

“Hang on a sec,” George said. “This reminds me of someth—”

“Come along. Let’s get a drink at the Edgewater and warm ourselves up.”

“Happy holidays, gentlemen. What can I get you?” Simon didn’t seem at all surprised that George had returned so soon to the bar.

“Glass of milk, please,” Terrance said.

“And I’ll have another.”

“Another . . . milk?” Simon said.

“No. The usual.”

“And that would be?”

“Come off it, Sime. You know very well.”

Simon smiled. “Sorry, must be a bit foggy tonight. Refresh my memory.”

“What you served me half an hour ago; what you’ve been serving me practically every weeknight for the past ten—no, more like twelve years.”

Simon looked amused. “Listen, pal, maybe you’d better stick with milk. Or coffee. How about a nice hot cup of coffee?”

“I want a Bushmills on the rocks, and you bloody well know it.”

Simon moved off and began preparing the drinks.

Terrance said, “Relax, George. He doesn’t know you.”

“Of course he knows me.”

“How can he if you’ve never been born?”

George laughed and shook his head. “Whatever.” But something in Terrance’s smile made him pause. He scanned the bar. The Ryan twins were still playing darts. The same group of teens was playing pool. The monitors still flashed their trivia. Bad Christmas music continued to issue from the jukebox.

“Cheers.” Simon said, placing their drinks on the bar. “That’ll be six seventy-five.”

“On the tab, please.” George lifted his glass and sipped.

“And what tab would that be?”

“My tab.”

Simon’s amiable expression morphed into something less benign.

“George Bayliss’s tab—you know, George Bayliss, the guy who approved the loan that allowed you to buy this joint in the first place. The guy who gave you a ten-dollar tip a half hour ago. ”

Simon sighed. “O.K., you know what, pal, I don’t know what you’re on about, but I’m really not in the mood. That’s six seventy-five, O.K.?”

George knew he had spent his last twenty but thought perhaps he could squeak six seventy-five onto one of his beleaguered credit cards. He reached for his wallet, but there was no wallet. His pants pockets were empty. He must have lost it in the river.

Simon folded his arms across his chest.

“Do me a favour and pay for this round,” George said to Terrance.

“Oh, I don’t have any cash.” Terrance giggled, a milk moustache shining atop his lip. “Angels don’t carry money, you know.”

“O.K., that’s it—” Simon leaned forward on the bar.

“Wait,” George interrupted. “Get Andrea. Andrea offered to buy me a drink earlier.”

“Andrea? Andrea who?” Simon asked.

“Andrea Sloane.”

“Andrea Sloane’s not here,” Simon said, looking around the bar.

“What are you talking about? She’s working tonight; she was my waitress a half hour ago.”

“O.K., Merry Christmas. Drinks on the house, boys, but I’d like you to finish up quick and skedaddle. Savvy?”

“I tell you, Andrea Sloane is working tonight!”

“Andrea Sloane doesn’t work here, pal. She’s never worked here. O.K.? Good night.” Simon snatched up their glasses and emptied them into the sink.

“Much obliged,” Terrance said, wiping his mouth with his sleeve. “A Merry Christmas to you, sir.” He slid off his bar stool and took George by the arm. “Come along, George.”

“But I just saw her. She spilled a tray of drinks on me. She thanked me for getting her this job!”

Terrance pushed George toward the exit. He manoeuvred him out the door and onto the snowy street. “No, George, you didn’t help Andrea Sloane get a job. How could you recommend her for a job if you had never been born?”

George stared at Terrance. “But she just said . . . Oh, I’m confused. I could’ve sworn she just said . . .”

“What, George?”

“That she didn’t know how she would’ve made it through the holidays without that job. She has a son you know. He’s five.”

“I guess we’d better check on her, then. Since you weren’t alive to get her that job, she must be in a bit of pickle, eh? Come on.” Terrance took George by the elbow and steered him up the street and around the corner to Mercer’s Department Store. He tapped on the glass picture window. “Have a gander.”

George peered through spray-on snow, past the Xbox display, to the cash counter where Andrea was ringing up a teddy bear dressed in a Santa Claus suit. She looked different than she had in the bar. Her hair was now in braids. And she was wearing a green sweater instead of a red jersey.

“That’s weird,” George said, as he wandered to the entrance and into the store. “Andrea.”

She looked up.

“You work here now?”

“Um . . . do I know you?”

“You don’t know me?” George said, approaching the counter.

She smiled, confused. “Sorry. Should I?”

“You don’t know me? George Bayliss?”

“Oh,” said Andrea, handing her customer a credit-card slip to sign. “Are you related to Harvey Bayliss?”

“Of course. He’s my brother.”

“One sec,” Andrea said, completing the transaction. “Merry Christmas!” She handed the bagged bear to the customer and turned to George. “I didn’t know Mr. Bayliss had a brother. I guess you must be in town for the holidays?”

“I guess.”

“Hey, are you all right? Where are you going?”

George stumbled out of the store and slumped on the bench where Terrance was seated, head back, mouth open, catching snowflakes on his tongue.

“This is crazy. I don’t get it.”

“It’s really very simple, George. You weren’t there to put in a word to Simon about Andrea, so she had to keep trying to find work. That’s how she landed the job at Mercer’s. She doesn’t know it yet, but she’ll be managing the place someday.”

“Oh.”

“And because they close in half an hour, Andrea won’t be toiling all night in a smoky bar. She’ll be able to spend Christmas Eve at home with little Timmy.”

George sat on the bench and took it all in. He took it all in and said, “O.K. Fine. Maybe I didn’t have such a big impact on Andrea Sloane’s life. But she said she knew my brother, Harvey.”

“So?”

“So my brother wouldn’t be alive today if weren’t for me.”

“Is that right?”

“Yes. That’s right. When we were kids we went tob—”

“Tobogganing. I know.” Terrance stood up and began walking toward the park. “And Harvey’s Snow Warrior went out of control, and he slid onto the river and went through the ice, and you sped down the hill and inched your way out and lay down on your belly and fished him from the water and blah blah blah blah blah.” Terrance said it as if it were a boring speech he’d been forced to recite every morning for ten years.

“And let’s not forget,” George said, trailing behind, “Harvey’s practically a hero in this town. He saved the life of a pregnant woman who was in a car accident! Pulled her right out of a burning automobile and rushed her to the hospital in his car. He saved two lives that day, which means I saved three, if you think about it.”

“Well, George, that’s not entirely accurate.” Terrance pointed to a steep hill at the south end of the park in which they now stood. “Shall we go back to that supposedly fateful day?”

Before George could answer Terrance waved his hands, and in a flash they were standing at the base of the tobogganing hill. But now it was day. The sun was shining, dogs were barking, children were moving up and down the hill. George recognized his peers from long ago: There was little Marcy Hargreaves, and there was Michael Weigand and Daryl Samotowka and Cheryl Fields. And there was his future wife, Marianne Cunningham, so cute in her pink parka and woolly white cap. “This is incredible!” George said, running up the slope, dodging toboggans. “I don’t see me. Where am I?”

“Duh. You were never born.”

“Where’s Harvey?”

“He’s not here,” Terrance said. “Harvey’s at home, watching television. Remember? It was your idea to go tobogganing that day. Harvey wanted to stay home and watch cartoons.”

“I don’t recall . . .”

“If you’d never been born, Harvey wouldn’t have ended up in the river in the first place.”

“Oh. So he’d still be around to rescue that pregnant woman when the time came?”

“Right. But it’s not such a good thing, George, truth be told.”

“How can you say that?”

Terrance waved his hands and they were alone again in the dark park. “That woman’s son, Paul, is going to grow up and become a serial killer. He’ll take the lives of sixteen prostitutes and one tow-truck driver before he’s caught.”

“Holy Hannah.”

“Now had you been born and failed to save your brother, that would’ve made an impact.”

“Oh . . . But wait a minute, what about all my civic actions? You know, I spearheaded the Be Nice, Clear Your Ice campaign. Who knows who might have slipped on a sidewalk and killed themselves if it weren’t for me?”

“I know, actually. Nobody slipped.”

“Well, what about the Ride-A-Thon I organized? We raised funds to erect a statue of our town’s founder.”

“Didn’t think you’d inquire about that one. Let’s check it out.”

George followed Terrance to the lighted south entrance of the park where the bust of William Fenton III should have been sitting.

“Aha! Not here, is it? Just this puny little plaque that’s been here forever.”

Terrance gave George a pity smile. “Well, you got me there, baby. It’s true. If you had never been born, that chunk of bronze would not exist.”

“I admit it’s not much,” George said, suddenly sheepish.

“Especially since the artist you commissioned did a terrible job.”

“You think?”

“Looked as if Fenton himself had been made of bronze, if you know what I mean. And that pink marble pedestal . . .”

“I’m not really an expert.” George chewed a hangnail. “But you know something, pal, it’s not about the art,” he said, rallying, “it’s about the pride.”

“O.K.”

“And anyway,” he said, following Terrance out of the park, “there are other things I’ve done. Truly worthwhile things.”

“I’m all ears, Georgie.”

Well, what about my mom? I’ve been giving her three hundred and twenty dollars a month for the past five years. Without me—”

“Social security. Plus, with only one child to raise, she was able to sock away some dough for her golden years.”

“Oh. O.K. Well, what about all the risky loans I’ve approved for people in this town? All the opportunities I’ve created and dreams I’ve fulfilled?”

“Without you around to do so, the Morton family took over the savings and loan. Heidi Morton does your job.”

“Really? Heidi Morton.”

“Turns out she’s just as nutty and generous as you when it comes to doling out the cashola. But unlike you, when the bank founders, she has a wealthy father to step in and personally save her and the company.”

“I see.”

“Are you all right, George?”

“Yeah, I’m just—I feel a bit dizzy.”

“Do you want to sit down?”

“No.” George took a couple of big breaths. “No, sitting down is not what I want to do.”

“Hey, where are you going? Hey wait up . . .”

“I’m going home,” George called out. “I have to see my wife and kids.”

“But you don’t have a wife and kids.”

“Well, Marianne then,” he yelled, as he jogged down Wellington Street. He sped up and turned right on Croft, then left on Pineway until he stood, panting, in front of his house—No. 72. Terrance was waiting on the porch when he arrived.

“I detest jogging,” Terrance said.

“Does Marianne still live here?” The house looked the same, except for a more elaborate Christmas display, which included a rooftop Santa and sleigh complete with illuminated reindeers that appeared to have just lifted off the shingles and taken flight.

“Yes,” Terrance said. “Marianne always loved this drafty old house. But wait,” he caught George’s wrist before he could ring the bell. “I’d better show you something first.” Terrance waved his hand, and in a flash, he and George were standing in the living room of 72 Pineway. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I’ve made it so they can’t see or hear us.”

Two children were watching television and eating a Chocolate Orange. The house smelled like roast turkey and balsam fir.

“Is that the one what stole Christmas?” said the girl who looked a lot like Zoey but wasn’t Zoey. Her small face was smeared with chocolate.

“No, stupid head,” said the boy who looked quite a lot like Matthew but wasn’t Matthew. “That’s Billy Bob Thornton.”

“This is very disturbing,” George said. “Where’s Marianne?”

“Upstairs. But you might not want to—”

George found Marianne in the bedroom. She was seated cross-legged on the bed, watching her favourite decorating show on television. And seated behind her, also watching the decorating show—something George had long refused to do—was Dennis Cole. He was massaging Marianne’s shoulders.

“Yeah,” said Marianne, “that’s good right there.”

“I don’t believe this. I really can’t believe this.”

“Why not?” Terrance said. “Dennis Cole is a nice guy and, as it happens, a good father and a fine husband to Marianne.”

“Yeah, I know he’s a nice guy. He’s my neighbour, or at least he was my neighbour. I just—damn it. I always thought Marianne and I were soulmates, you know? Like they say that each person has one true match out there. I thought we were ‘it’ for each other.”

“So you figured if you’d never been born Marianne would remain single, grow old before her time, and become a dour spinster with bad glasses and her hair pulled too tight in a bun?”

“Well . . . something like that. Yeah.”

“Sorry, George. If you want to know the truth, this is Marianne’s third marriage.”

“No way.”

“Way. She also had a number of lively dalliances before getting hitched the first time. And not just with men.”

George sank onto the edge of the bed and stared at the floor.

“Is that not the most hideous window treatment you’ve ever seen?” said Dennis.

“Hildi’s the worst,” said Marianne. “But I like the pink paint. Maybe we should do something like that in Zoey’s room.”

“If you like.”

George leaped up and grabbed Terrance by the lapels of his overcoat.

“I have to get out of here. Now,” he said, hyperventilating. “Please, Terrance, get me back. I don’t want to be unborn!”

Terrance waved his hand, and in a flash he and George were standing at the edge of the river where they had first met. George paced the bank until his breathing slowed to normal.

“Now that you exist again, do you feel better?”

“Not really. I feel depressed. I honestly thought I had made more of an impact. Now everything seems so random and meaningless.”

“Sorry, George. I told you, it hasn’t been such a wonderful life after all.”

George sighed. “I enjoyed it though . . . until the financial-ruin part. I mean, isn’t that enough?”

“You tell me.”

George stared out over the dark river. “Maybe,” he said, his eyes brightening, “maybe I could try much harder to have a positive effect and make a difference. Like this woman I read about in the paper last week, a surgeon who runs a free clinic in Ethiopia for young girls who have fistulas—holes in their bladders from giving birth when their pelvises are too underdev—”

“Yes, yes,” Terrance interrupted, “I’m familiar with the condition and the surgeon.”

“Maybe I could do something like that?”

Terrance didn’t say anything, he just shrugged. And slowly, the light in George’s eyes dimmed as he realized he would never do something like that.

“Well, George, the way I see it, you can either jump into that water or return to your family and resume your life.”

George walked away from Terrance, to the edge of the river. He thought about going home. Earlier in the evening he had confessed to Marianne that the money situation was far worse than she could possibly imagine. But maybe, just maybe, she wouldn’t be so angry anymore. Maybe worry would’ve taken the place of rage and she’d be waiting up when he got home. Maybe, since it was Christmas Eve, the kids would be keeping a tender vigil as well. He would be greeted with shouts of relief and joy—“Daddy! Daddy!”—as he came through the door, his arms open, soon to be filled with family. And maybe Marianne would’ve spread the word to his friends and customers, and maybe they’d be coming by with words of support, and maybe not just words.

Oh, it almost made him cry to think of it. Unlikely, though, that the townspeople would rally so quickly on the eve of a major holiday. Probably it would just be Marianne waiting by the fire, the kids already in bed. Or maybe he would go home and find the doors locked, like the last time he stormed out after an argument. Maybe he would have to crawl through the basement window, where, if he were lucky, he would find a pillow and one of those itchy wool blankets dumped on the futon couch. Maybe Marianne would be locked in the bedroom, stinking up the place with the cigarettes she smoked one after another when she was furious. And maybe the repo men had already been there to take back the plasma-screen TV George had bought her for Christmas. She might scream at him about the money he’d been giving to his mother every month or call him a selfish prick for disappearing on Christmas Eve and making the kids worry. There really was no way to know.

George gazed up at the lighted bridge. He stared down at the swirling black water.

Terrance inspected his fingernails. He whistled “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” and used a rock to scrape mud off his Wellingtons. “Come on, George,” he said, straightening up. “Make a decision, off you go.” But when he turned to the edge of the riverbank, George was no longer there.