Montreal, 8:30 A.M. The height of the morning commute. The Berri-UQAM station is packed shoulder to meticulously dressed shoulder. I stride across the tile, iron in one hand, my board, Simone de Boardoir, in the other. I have twelve white shirts, twelve hangers, and a bungee cord in my red backpack.

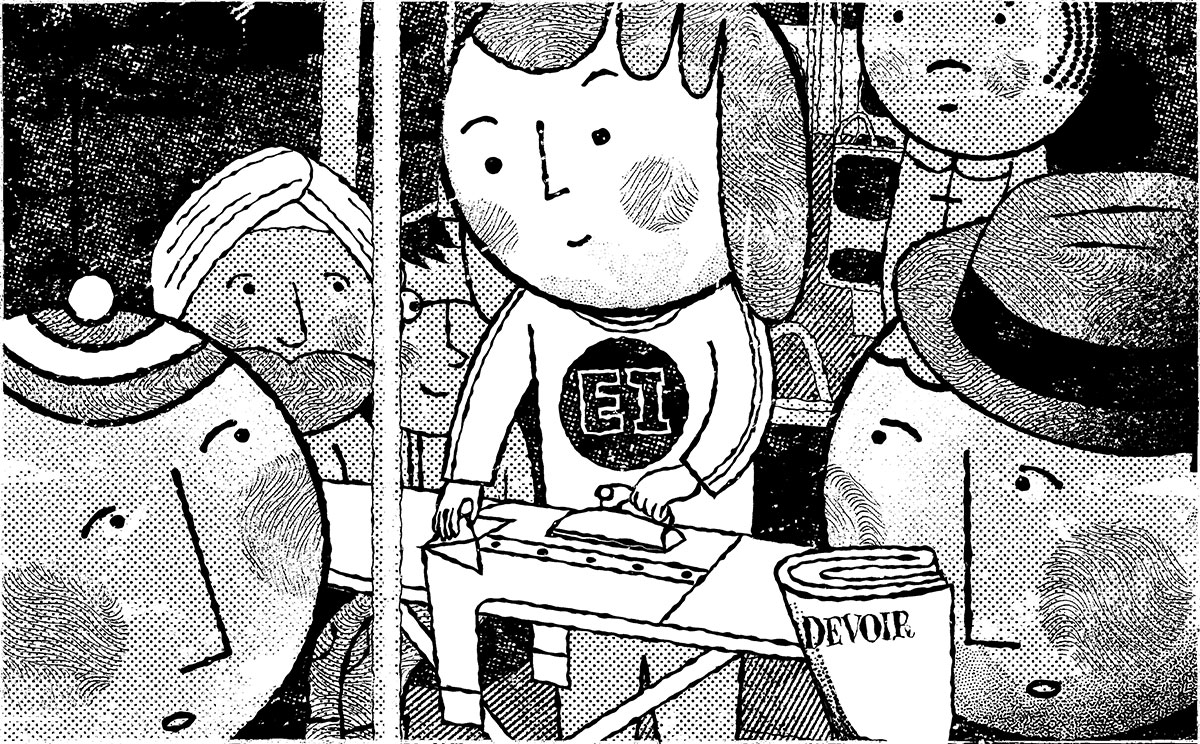

The metro rumbles into the station. I hang back as the doors open, bolting in at the last moment. I’ll have just enough space in the standing-only area near the exit. A tall man in a suit hangs onto the support bar with one hand, reads Le Devoir with the other. I clip the bungee cord between two supports, flip Simone’s legs down, unzip the upper pouch of my pack. Twenty-five seconds. My portable electric iron has been warming up since I came down the escalator. I pull a shirt from my bag and focus on the ironing.

Shirt 1: Pressed in thirty seconds. I hang it up on the bungee cord line.

Shirt 2: People are staring. I ignore them.

Shirt 4: I’m jostled, but maintain my balance.

Shirt 8: I hear people asking questions. (“Hey, what is she doing? ” “Qu’est-ce qu’elle fait là? ”)

Shirt 9: A guy in a T-shirt and jeans holds up a camera phone. I hold the shirt in front of my face.

Shirt 12: Done. Jean-Talon station comes into view. Simone folds, the bungee cord comes down, shirts hook onto the back of the board, iron switched to Off.

I’m the first person to leave the train. I push my way to the elevator no one uses, disappear.

IRON MAIDEN BAFFLES METRO RIDERS

An unidentified woman, bearing the logo “EI” on her jersey, for “Extreme Ironing,” appeared on the metro yesterday, ironing a reported two dozen white shirts on the orange line, between Berri-UQAM and Jean-Talon stations, before disappearing. Conflicting reports suggest the woman either transferred to the blue line or fled up the escalator.

A spokesperson for the London-based Extreme Ironing Bureau, who calls herself “Gertrude Steam,” said extreme ironing is an emerging sport, practised by an estimated 1,500 participants around the world. It is judged on the merits of danger, ironing quality and speed.

Extreme ironing has no known connection to any terrorist organization.

“I saw the ironing woman this morning on my way to work,” said Monique LaFlamme, a retail sales manager. “She ironed so fast I knew she wasn’t doing last-minute laundry. It was skill.”

Others were more skeptical.

“This is the kind of arty thing that happens in Montreal all the time,” said Joey Tremblay, a McGill University student. Tremblay tried to snap a cellphone photo of the woman ironing, but she hid behind a pressed shirt.

“Why the anonymity? ” said Tremblay. “This woman should identify herself and do this in a gallery.”

Citing the right to privacy of its competitors, representatives from the Extreme Ironing Bureau declined to comment on the woman’s motives or identity.

Transit authorities investigating the incident declined comment.

—Montreal Gazette.

Back home, in Ottawa, I read the article out loud to my cat, Barnacle, who twitches his tail in mute appreciation.

“Page A6. Not bad, eh, Barnie? We beat their coverage of the B.C. election.”

I fold the newspaper around the article, ironing the creases on Low so they’re sharp, perfect, and cut it out along the iron lines with an X-acto knife. I place the clipping between the pages of my hardcover edition of The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing. Tomorrow I’ll take it to work and make four clandestine photocopies: one for the bureau, one for my brother, one for my dad, and an extra copy for myself. I hate the way newsprint yellows as it ages.

I’ll send my dad’s copy along in his next bundle of pressed shirts.

I pick up the phone to call George, my one friend here in Ottawa. Another Prairie transplant. The most popular kid I knew in high school, back in Winnipeg, George moved here long before I did. The year I arrived, he used to drag me out to the Lookout or Icon to go dancing, but he was always cruising, while I sat in the corner drinking whisky sours and watching beautiful gay men dance suggestively with each other. It was a frustrating experience for a straight, celibate (by default, not choice) woman. It’s difficult to meet an available hetero man at a gay bar. I couldn’t hear enough over the crashing dance music to make any new friends. Eventually, I stopped going. Not that I ever go anywhere else to meet anyone. I like staying in. George teased me about it so much that I now meet him for brunch every Sunday at the Manx Pub, where he gives me a full weekend report about his friends and lovers.

“George!” I say when he picks up. “Check out the on-line edition of the Gazette.”

“Hi, princess. Let me just disconnect Instant Messenger…et voila. What am I looking for? ”

“Oh, you’ll know when you see it,” I say. “I’ve got to get back to ironing.” I hang up.

A new parcel. I slide a box cutter through brown paper, unwrap four dirty white shirts for the hamper toss. A copy of my dad’s new business card is stapled to a letter printed in his favourite typeface. On his law firm’s stationary.

DEAR LUCY,

Here is my new business card.

The partners chose blue this year.

Keep working hard.Love, DAD

For my dad, it’s a thoughtful note. We’ve made progress. I affix it to my fridge with a flower magnet my mom gave me once.

I shine my iron’s handle with the hem of my Björk T-shirt while waiting for it to beep Ready. I set my digital egg timer to thirty seconds—I need to keep training. I grab a shirt.

I’ve improved on my mother’s and grandmother’s lackadaisical method (sleeve, flip, sleeve, flip, cigarette drag, collar, back, sides, cigarette drag, button placket). My technique is about speed: I stack shirt sleeve on top of shirt sleeve for one hard press, fling fabric into air, swoop over back, sides, and button placket, leaving the collar for last. I’m so fast, I can iron without scorching.

Extreme ironing was George’s idea. A joke about spicing up my after-work life. “If you have to do your dad’s ironing at least be feminist about it,” George said. “Go iron those shirts on top of Mount Everest.”

I started training about four months ago. Just about the time the antidepressants started kicking in. The Montreal subway was my first E.I. event, but I plan to do more. I will target urban jungles: New York, Paris, London, Tokyo. All dangerous now that stealth or strange baggage can get you arrested as a suspected terrorist.

It makes me feel a little like a spy, and less like a Canadian federal civil servant.

At least I don’t come home from work and lie on the sofa in my pyjamas crying anymore.

The day my mom died of a sudden heart attack, I was at work in my cubicle on the thirteenth floor of a government office tower on Kent Street. National headquarters of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Communications branch, Maritime division. Playing solitaire on my computer. I left at five, walking straight home to my downtown apartment. My dad called me at 5:35 with the news, having calculated the time difference between Winnipeg and Ottawa. He’d waited for me to finish my day at work. My job “on the Hill” has always been important to him.

My dad used his calm, reassuring, tax lawyer’s voice. I paced my reaction, maintaining control long enough to arrange a flight, read my credit card number over the phone, and pack. At that point, feeling the electrical storm coming, I shakily called a cab and got the earlier red-eye to Winnipeg. The flight wasn’t full. The seat next to me was empty. I buckled in, watched the video-projected safety demonstration, then felt the whites of my eyes melt, begin draining. Once I lost control, there was no getting it back. The stewardesses gave me sympathetic looks, Kleenex, and glasses of water.

That night, a stream of tears fell out of the passenger windows of a Boeing 737. Freezing in mid-air, they dropped twenty thousand feet onto the fields below. Farmers from Ontario to Manitoba complained of crop damage. Mysterious hail.

Winnipeg was a blurry ride in my dad’s silver Cadillac from airport to home, home to church, church to cemetery, cemetery to home. My brother, Tim, a travel reporter, had flown in from Belarus for the funeral. There was a sodden, sullen family talk. I realized I was the only woman left in my immediate family. My grandmother had coughed through years of frailty, but her emphysema-riddled lungs continued to rasp until she was ninety-six. My mom surrendered. Exhausted at sixty.

I decided I wanted to stay home, in the house I’d grown up in. Yet home was my mother in the kitchen, laundry room, basement, garden, always working, puttering, and chatting. When I moved away, my mother wrote me long letters, with updates on all the neighbours, bugs in the garden, choices for new wallpaper or paint, the trips her co-workers were taking. She enjoyed her job. Her close friendships lasted more than forty years. She was unedited, spontaneous, and kind. The notes of encouragement she wrote to me spanned decades of lunch boxes, sleepover pillowcases, piano recital music, college care-packages—each decorated with little flourishes and illustrations she drew in the margins. I kept each one, keeping them flat, pressed, and safe in the pages of my favourite novels.

Now our house at the edge of town, sprawling after years of additions and hapless renovation, was moist and empty.

Tim seemed to expect room service. Mom had turned Tim’s old room into a computer room shortly after he left, so he stayed in the guest room, used my shampoo, and waited for coffee to be made. We didn’t have a chance to talk—he left the day after the funeral without making the bed, flinging himself farther into Eastern Europe to write for U.S. magazines about Latvian flower boxes and the resurgence of traditional Ukrainian embroidery patterns.

Tim’s eyes had been misty, wistful. He’d been away for a long time. Physically and mentally.

I slept on the rec room couch until my tear ducts became infected. I couldn’t bear to stay in my old room. My mom’s vacuum was still in there, her duster and her caddy of cleansers and shammies left on the bed. She died on cleaning day. The day before laundry day. My dad quickly ran out of clean shirts.

Spending my evenings ironing my dad’s shirts reminds me of being six, of silently staring at my grandmother hunched over her built-in wooden board in the old farmhouse kitchen. She smoked with one hand, and ironed tablecloths and tea towels with the other.

Feeling a hot iron spit and steam in my hand reminds me of being eight, of learning multiplication tables at the orange study carrel in my parents’ basement, right beside my mom’s oversized, yellow-padded ironing board. That’s where my mom, a dental hygienist, used to hum old show tunes while she ironed her pink and blue cotton uniforms, my dad’s shirts, my dresses, tops, and pants. I don’t ever remember her ironing anything for Tim. He liked the rumpled look. Still does.

The smell of hot cotton and polyester, the surging hiss of steam, the sound of the iron clicking against buttons belongs to me. I smile, place another shirt on a hanger, watch Barnacle paw at his squeak toy. The phone rings.

“Hi, George,” I say, knowing who it is before he says anything.

“Dear God! Not only did you leave your apartment, you left the city,” George says. “That was you in Montreal. I know it was! You secretive little thing—next time you need to bring me along, though, and afterward we’ll go out for a little fete.”

“Of course,” I say. “This was just a little experiment. Next time will be a bigger deal. I’ll probably need some help.”

“I am so there, honey.”

“So brunch Sunday? ” I ask expectedly.

“Oh Lucy! I forgot to tell you! I’m flying back home to Winnipeg this weekend for a little anniversary soiree at my parents’ farm. It’s their thirty-fifth shindig, so I can’t miss it.”

“O.K.” I pause. “Say hi to everyone for me.”

“I’ll celebrate with you when I get back, O.K., doll? Don’t stay cooped up indoors all weekend!”

I hang up the phone, pick up my long-necked silver watering can, and add more water to my iron. I finish my dad’s shirts and decide to stay up late ironing all my bedding.

My dad wouldn’t let me stay in Winnipeg. We had an embarrassing—for both of us—showdown in my mom’s kitchen a week and a half after the funeral. He was already back to work. Five business days after my mom died, he had excused himself from a small luncheon of crustless sandwiches thoughtfully prepared by my mom’s lady friends and descended into the basement. Moments later, I looked out the front window to see him throwing his big leather briefcases into the backseat of the Cadillac. He got into the driver’s seat, reversed the car into the tree-lined street, and sped away without looking up at the house. I had my hand up, ready to wave like Mom always did. I put it down and sunk into the back of the good floral Chesterfield and stayed there, becoming a bulbous orange flower, part of the house’s pattern. I thought I was the only one who could keep our home tidy the way Mom liked it. I would make sure nobody took Mom’s needlepoint pictures down from the living room walls. I would read her romance novels, keep the dust off her extensive library of family photos.

When Dad came home and saw me wiping down the kitchen table, he said, “You’re too smart to be doing that Lucy.”

Later that evening, when he saw me reaching for a Kleenex, he said, “Snap out of it, Lucy. “

The next morning he sniffed at the bacon and perfectly timed over-easy eggs I’d spent almost an hour trying to figure out how to make, and reached into the cupboard for a box of cereal.

I launched Mom’s dog-eared copy of The Joy of Cooking at him. It bounced off his shoulder with less impact than I’d hoped.

“I want to help you!” I shouted. “What’s wrong with you? ”

“What’s wrong with you? ” he yelled back. “You’re not your mother!”

I looked at my dad, at his narrow age-stooped shoulders and rounded belly. The red ceramic light fixture above the kitchen table swung gently back and forth, and when he sat down, the top of his bald head shone. I stared at him, realizing he could get all the support he needed from the Rotary Club, but that his good work shirt was wrinkled.

That night, my dad and I ordered pizza—half pepperoni (for him), half vegetarian (for me), and we sat down and talked about my career “on the Hill.”

“You have a future in Ottawa,” my dad said. “You have a really good job.”

“But I don’t really know anyone there,” I said. “Except George.”

My dad sighed. I hate those steamroller sighs. I flew back to Ottawa, taking some of my mom’s needlepoint and photos with me. And a bundle of my dad’s shirts. We’ve been sending packages of them back and forth ever since. In ten months, not a single parcel has gone missing in the mail.

My freshly pressed purple pillowcases and striped duvet cover are folded on the table. I’m working on the fitted sheet when the phone rings again. I’m startled this time—I don’t often get two calls in an evening.

“Hello? ” I say tentatively.

“Hello, Lucy, It’s Dad,”

My stomach flutters. Dad rarely calls.

“How are you, Dad? Did you get the last package of shirts? ”

“Yes I did, thank you.” Dad takes a deep breath. “Lucy, I’m calling because I’m selling the house. It’s too big for me. I’d like to move into a nice condo by the river.”

He doesn’t say it, but he is also wriggling out from underneath our laundry business. I turn my iron off, sit down on the hardwood floor, and hug my legs. My jeans bunch uncomfortably under my knees, and I let go.

“Lucy? ”

“O.K.,” I say. “It’s O.K., Dad, I’ve been expecting this.”

“Obviously I’ll have to get rid of some of our things. This is a large house—too big for one person. Is there anything you need, that you would like me to send to Ottawa for you? ”

“Can you send me Mom’s ironing board? ” I say, imagining the basement, the living room, the kitchen, the bedrooms of our house. In my mind I walk down the hallways and up the stairs, opening and closing doors, fighting to remember every detail, to archive our home in my memory. Between Dad, Tim, and myself, only I will remember the place under the stairs where we used to keep the fake Christmas tree, what Mom’s rocking chair looked like, the exact number of steps from the sunken living room to the kitchen. The house is a museum of my mom, and the museum is closing.

It’s a week later, and it’s well after 9 P.M. by the time I leave the office. I shuffle through the December snow, aware of every crunching step. The streets of downtown Ottawa are so deserted, I expect a giant lizard to spring from the top of the Quickie Mart. Or a door-front gargoyle to begin melting ice with hot exhalations at the foot of a crumbling apartment. I am four mugs of coffee and a twelve-hour workday beyond the threshold of surprise. Even staring intently at the glittering snow feels hallucinogenic. A taxi glides by, slows as it passes me, then speeds up, fishtailing. I don’t need a ride.

Fingers too raw with cold to flick my lighter, I huddle over a large grate in the empty parking lot behind the C.I.B.C. From my briefcase, I pull the final version of the press release I wrote then revised twenty-three times over the course of the day and rip it into tiny pieces. For every level of hierarchy it advanced there were new changes that had to be approved and reworded by communications specialists at the P.M.O. By the time it was finished, not a single word of my original remained. Now, buttressed by multidirectional winds, the fragments float in a spiral of centrifugal force, before falling down and through grate gaps into permanent darkness.