Susan woke up in grey sheets with a dry mouth and a queasy stomach. She ate out of cans at home. She hated the sun. She used to be a publicist for a hip TV station, but she now worked writing press releases at a government office, where she usually accomplished only two hours of work in her eight-hour day. Like a cow tied to the trough, she had become motivated only by appetite: coffee in the morning, smoke at break, usually a sweaty, too-salty lasagna with iceberg lettuce for lunch, and, finally, a bottle of wine when she got home. Coffee, smoke, lunch, smoke, bottle, and many more smokes. Susan was thirty-five, fifteen pounds overweight, and divorced.

The divorce was five years ago—so long that it felt like she had never been married. Susan and Fred’s tight two-year courtship had stalled to a slow, appalled feeling a week before the wedding, but they went through with it anyway; they had already booked the city’s most popular swing band for the reception. They did not wound each other unduly in the divorce one year later. It turns out a job at a TV station and consistently cool footwear are not the best measure of suitability as a life partner, but then again, what was? Fred discovered that Susan, in spite of her ability to turn a phrase, was not really Dorothy Parker. Susan discovered that Fred was jaw-droppingly shallow and that he expected her to clean the toilet. During their time together, Susan and Fred threw theme parties—their scotch-tasting party on Robbie Burns Night was a legendary orgy; they even had haggis—and went on road trips to rural areas that made them giggle. Susan had always felt beautiful, but of course they were drunk every night. Fred had been hysterically interested in sex—any sex—and had assumed a “naughty” air about it that was delicious at first. Later, Susan suspected he might be gay.

After the divorce they both left their warehouse digs. Susan left the TV station, as well. She now rented a small clapboard house with a sagging front porch on a concrete slab—the kind of house built in the nineteen-forties for labourers to live in while they were building the mansions two blocks over. At sixty years old, it was rotting and the joists creaked. The windows leaked cold in the summer and heat in the winter. It was very dark, and Susan had never had the confidence to tear down the faded urine-and-dusty-rose-coloured wallpaper in the living room, the first room you saw when you entered the house. Fred would have whipped the place into shape in no time. The one window facing the street held crooked yellowing blinds that winked lewdly at passersby. Furniture-wise, Susan had inherited the do-not-pay-until-1999 (that was in 1998) overstuffed couch and armchair from her marriage. They were huge, the backs of them swollen with puffy, hunched pillows. The couch pushed you off when you were sitting and gathered you in if you were lying down. Black with pink slashes, they were covered in a fabric that served only to remind one how appalling the previous trends were, let alone imitations of those trends generated by discount textile warehouses

Fred had moved on to score a condo. Susan hadn’t realized he had that much money. She guessed his parents came through when he finally got rid of her. Susan jealously imagined the condo furnished with the requisite new furniture, all-chrome kitchen, chocolate-brown walls, and fake-fur pillows. He was still producing at the station and was now dating one of the tiny, haggard television anchors, a girl who looked remarkably like Fred in drag. Susan was, if not glad, relieved to be rid of Fred, but she still switched the channel whenever his little television hostess came on and the credits rolled by.

Susan’s house was attached to an even more rundown house next door. Those windows that weren’t boarded had tinfoil on them. A lot of the houses in her east-end neighbourhood had tinfoil or sheets on the windows. Susan could understand the sheets, but not the tinfoil. A tattooed man in his thirties and his seventeen-year-old girlfriend lived in the house next door. They may have been squatting, Susan didn’t know. Besides saying the occasional furtive hello and hearing their beery yelps in the summer, she had very little contact with them.

When Fred went so did most of Susan’s social life, but Susan’s friends were appalling, anyway. Working in the media world, she had slipped into hanging around too many bars and openings and had aligned herself with people who had great hair and no character; people whose savage self-interest would cause them to dump, ditch, betray, or, even worse, forget Susan in an instant, however much they protested at three in the morning, drunken tears in their eyes, to be loyal and faithful friends. Just like right after the breakup, when she drove to Carnaval, the winter festival in historic Quebec City, with her friends Omar and Paula.

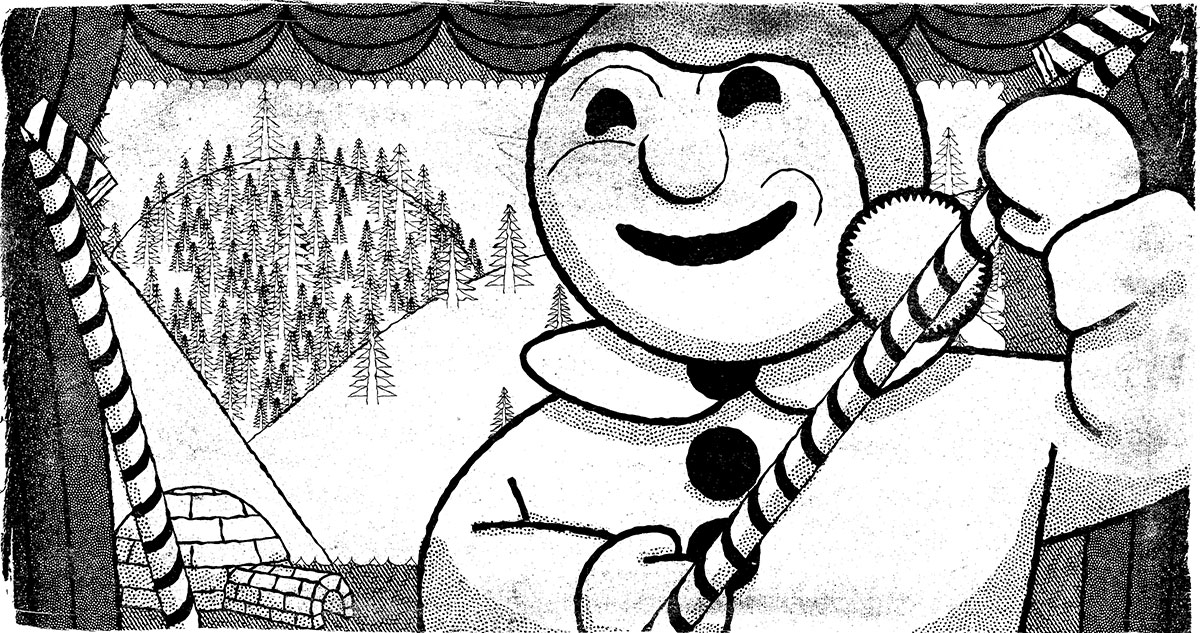

Fred and Susan had been crazy about Carnaval. It had a mascot they adored: Bonhomme Carnaval, a roguish white snowman with a red cap and a sash, rather like the Pillsbury Doughboy. They had even built a sort of Buddhist shrine in their loft to a one-inch Bonhomme on a key chain. They surrounded it with Kinder toys and Pixy Stix.

Omar and Paula were blatantly using the trip as an excuse to cheat on their mates, and Susan provided a good smokescreen. In their erotic frenzy and greed for each other they somehow justified driving home without her. They weren’t monsters; they had it in their heads that they would contact Susan at the hotel with some vague emergency. Only they didn’t. Susan waited for them at breakfast, ate alone, then searched the hotel and finally called Paula on her cell, now five hundred kilometres away. Paula pretended to be cut off. Choking with incredulity and rage, Susan went over her Visa limit on the two-hundred-dollar train ticket home, and sat for eight hundred kilometres beside a white-haired lady who seemed very sweet until she casually remarked, “No wonder they get raped,” when a teen in tight jeans walked by.

Disposable Susan spent hours watching her reflection in the train window. Her sallow, boozy face flickered over acres of black-tree skeletons and snowy fields. By the time she looked away, a shabbier idea of herself had been pressed into her mind. She fed it glutinous white-bread egg-salad sandwiches and four Coffee Crisps, the only chocolate bars available on the train. Sometimes she looked at the dozing, dissatisfied face of the old woman next to her, leaking distaste from a drooping mouth and shivering eyelids. Between her drawn reflection and the old lady’s ire, Susan’s resiliency permanently slackened. When she got back she started drinking more at home and didn’t see her remaining friends as much. Paula and Omar were eventually found out and in the way of offenders, somehow managed to blame their victim for it. Susan lost another coterie. In any case, Susan’s friends were getting harder and harder to get in touch with as they got older and had accessory children or their own affairs and successes.

Until she was a teenager Susan had managed to find truly kind, centred people as her best friends. But she lost that gift. Perhaps the competitiveness of university, her generic underweight prettiness, her upper-middle-class background had ruined her character. She hadn’t noticed it going and now wasn’t quite able to define when her life felt less authentic, or when the goals of job, man, and house ceased to be attainable. She guiltily suspected it had something to do with gaining weight. “Could I be,” she wondered, “that shallow? ” She saw women older than she was on television talking passionately about weight loss and Botox and thought, “Does it ever end? ” A phrase kept going through her head when she saw people talking about plastic surgery. “Why get a nose job when you have a hunchback? ”

Sometimes she fell to her knees in the kitchen. She usually managed to drag herself up, but sometimes she just lay on her back and looked at the greasy ceiling. At these times she felt fortunate. She had never lay on her back and stared at the ceiling when she was with Fred. There was something luxuriously childlike about it.

One Sunday night Susan came home from a boozy, fruitless dinner party. She had been generally ignored there—having neither sex appeal nor job opportunities to offer anyone—so she had gone too far, secretly drinking the hosts’ scotch and constantly refilling her wine glass. Slamming the cab door and staggering up her gravelly, weed-infested path like a drunk housewife in a fifties melodrama (she really should tidy up the lawn a bit; it could be quite cute), she froze. In front of her was a skunk. Flat, furry spatulate head. Pointed nose. Waddling nearsightedly it passed by her unconcerned and disappeared under the neighbour’s front porch. She got through the front door and collapsed on her overstuffed couch, one leg lewdly dangling over the arm and the other on the floor. She sat up straight again. Skunk! She could smell it. She had never really noticed it before, assuming the sour air in the house was due to mouldy beams and damp particleboard. Now skunk was all she could smell.

The skunk nosed comfortably under the porch, glad to get back in the black, tight tunnel of dirt, the ensuing smell of minerals and mud. The humans didn’t bother her, humans never did. Skunks are confident animals. Besides, this person left food out for her all the time in her battered tin garbage can. The skunk was a female. She had three babies curled in the dark interior of the sub-porch. They had been born in May. They were four weeks old.

Susan dozed on the couch that night and dreamt of skunks coming through her front door and nesting in the corners. She woke up at five after nine. Late for work, her mouth filled with a sulphurous cloud, she decided to call in sick, something she had been doing way too much lately.

Her boss, Marta Vansyana, a middle-aged woman with a frowning maternal air, was not pleased. Marta had left Bombay on the arm of her arranged husband when she was twenty. She had two daughters and two sons, all of them imperious, spoiled, and embarrassed by their parents. Marta cooked and cleaned for them all while also being communications co-ordinator of Susan’s department. Marta’s husband worked for parks and recreation, riding around the city in yellow trucks with his cronies, smoking in the cab, elbow on the window, and performing occasional light labour.

Marta had black tire marks under her eyes and wore lipstick the colour of pink entrails on her now-sagging mouth. Like an eighty-year-old lady who still wears passion-red lipstick because that was the style in the fifties, not noticing she was sliding into hooker wear, Marta applied and reapplied magenta fusion all day—the colour respectable business ladies wore in 1985.

She unenthusiastically told Susan to get well soon. Marta was deeply and passionately perturbed by violations of procedure. She hated that Susan’s work was well-written and on time, because Susan was clearly not working the full eight-hour day. Accustomed to the unreasonable deadlines of the TV station, even with an average of five sick days a month, Susan was getting all her work done. Marta’s resentment of Susan burned deep, charring her eyes even further. She made a note to give Susan her first warning when she came back. Two warnings and, according to procedure, she could fire her.

Feeling the familiar combination of guilt and relief when she called in sick but indifferent to her increasingly unstable work status, Susan crawled up the worn stairs to her room and fell deliciously asleep for another four hours. She woke up again lazily, stretched, went downstairs, made coffee, and watched some bad TV. She could hear the couple next door fighting, the girl’s voice an animal-wild screech.

“Fuck you, you fuckin’ bastard! I hate you! I hate you!”

There was the rumbling bass of his voice.

“I fuckin’ buy all the groceries all the time. You fuckin’ do it once and you don’t even buy the real Cheez Whiz, you buy that fuckin’ fake kind.”

More rumbling.

“I can’t get a fuckin’ job. I’m going to my mom’s.”

The adjoining wall shuddered as she stomped out of the house. Susan put down her all-dressed chips (breakfast), slipped to her knees on her oversized couch, and looked through the cracks of her plastic blind. The next-door girl, plump in jeans and tank top, shrugged into her too-tight jean jacket, a cigarette in her mouth. She turned and her long brown hair whipped into her tilted brown eyes. She obviously had no idea how beautiful she was, and she never would, thought Susan, who had always made the most of her own uninspiring little face, mostly by staying a little underweight (though that was now over). Maybe when the girl became an old woman with a yellowing perm she would come across a picture of herself in her youth and wonder at her beauty. Now, her face was veiled in a horrible expression, mouth curled and eyes deepened, a face that had been picking fights since infancy. Susan and she had waited for the bus together on occasion, never speaking. Her eyes briefly met Susan’s and Susan idiotically ducked.

There was a knock on the door. Oh my God, she was about to have a screaming harpy at her door telling her to mind her own fuckin’ business. Susan wrapped herself in her battered blue robe and crossed her arms over her breasts, then went to the door and opened it a crack. Standing there with a smile on his face was the guy from next door.

He was wearing sweatpants and what looked like a rubber tank top. His hands were under his armpits and he was rocking a little on his heels. He smiled at Susan, an ingratiating smile that did not suit his face: high, wide cheekbones, a down-turned mouth, and bad black eyes.

“Hey,” he said. “I’m Larry? I live next door? ”

“Yeah,” said Susan. “Hi.”

“We got a skunk problem,” he said. Susan had never seen eyes so black.

Susan and Larry scouted the property and decided the skunk was coming in under Larry’s porch and digging across under the concrete base of her porch.

“I mean, I could shoot the little fucker, but all I have is a BB gun,” said Larry.

They decided the best course of action was to have Susan call the Humane Society and find out what to do.

Susan went back in the house and called the Humane Society. They had a prerecorded message. It was insanely cheerful: “You have reached the information line for skunks living on your property!”

Susan repeated the instructional message four times. It seemed overwhelming. She looked at the list she had made: flashlight, radio, cayenne pepper, galvanized steel mesh or hardware cloth. What the hell was “hardware cloth”? She did not look forward to telling Larry about the procedure. He would probably just want to throw a grenade down there. She got dressed in an oversized T-shirt and her increasingly too-small jeans and went over to Larry’s. His porch was sagging. On it sat two plastic white chairs with permanent grey streaks. Even the window was crooked. A Union Jack flag served as the curtain. She knocked on the door and his shadowy bulk appeared.

“So I called the Humane Society,” she said.

“Hey,” he said. “Wanna beer? ”

It was 2 P.M. on a Monday afternoon. “O.K.,” she said. She tried but couldn’t get a look into the house as Larry retreated, then came back out on the porch with two beers knuckled in one hand.

“Have a seat,” he said expansively. Susan sat down. The chair’s arm was snapped through and she popped backward for a second.

“Oh shit,” said Larry. “Let me switch chairs.” Susan protested then jumped up as he grasped her chair and athletically lifted it with one arm while switching it with his own.

“You got the bum chair,” he said. “Heh heh heh.”

Susan tried to laugh with him. It came out a little giddy and desperate. She felt like an uptight cartoon schoolteacher.

They sat for a moment staring at the parking lot across the street. June’s first breeze wafted by. For that moment Susan felt comfortable, even happy, sitting on a porch with the neighbour. She was drinking a beer at two in the afternoon and didn’t care. Then slowly a waft of skunk floated by. Once she’d identified it, it was impossible to ignore.

“Fuck, can you smell that? ” asked Larry.

“Yeah.”

“It must have just fucking moved here,” he said.

She explained to Larry what they had to do. He was nonplussed.

“I got a couple of extra radios,” he said. “I’ll go to the hardware store on my bike and get the steel mesh. You get that cayenne stuff.”

That afternoon, she and Larry worked. They found the one entrance hole in the dirt by his porch. Larry seemed to know what to do and began to insert the mesh around the perimeter of the porch right away, so the skunk couldn’t get out anywhere else. It was strange squatting inches beside him as he grunted and sweated, Susan’s nose sometimes in the black spray of his armpit hair, obeying his “Hold this” and “Pass me that.” She was terrified of her hands slipping at a crucial moment, and when she crouched, the neck of her T-shirt gaped open, flashing a view of everything down to her soft belly. She also stunk, not having showered after the boozy party of the previous night.

Was the skunk worried? Did it hear all the scraping and muttered conversation? Did she curl her babies closer to her? Did she know this was the end? That would be impossible. To survive as serenely as she did she could not have the anticipation of a god, only that of a rodent. Sedated by her nursing kits, who were beginning to spray involuntarily with their infant lack of control, she waited until an inner trigger told her to go get food. It could be days.

Susan threw the cayenne pepper into the hole. Larry got out a bright yellow boom box. “Waterproof,” he said. “We’ll play some metal.”

“It says talk radio is better,” said Susan.

“Fuck, we may as well play some CDs and have a party,” he said.

On went the Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Tragically Hip, and Our Lady Peace. Larry played them loud. Susan hated this music. Her tastes were a bit more twee than high-school hard rock, which sounded like children’s music to her, with its corny crescendos and bad lyrics, like the first poetry efforts of a very slow teenager with an overdeveloped sense of drama. Susan dutifully listened to whatever darling of the indie scene was playing at the hipster bar where she used to meet her friends. She was used to music drenched in irony, with coy references to Beatle-esque movements. Larry’s music reminded her of a time in a musty basement when she had a crush on her best friend’s older brother. She caught herself nodding her head to one of the classics and stopped. “Oh my God, I was almost headbanging!” she thought.

When people coming home from work shot them dirty looks, Larry would raise his beer and say, “Sorry, man, got a skunk down there,” or “Skunk, man,” or “Doin’ a little exterminating.” The person would smile immediately and say things like, “Well don’t send him over to me. I just got rid of mine,” or “Hey, you can come to my house next!” Susan, who hadn’t experienced anything akin to camaraderie in about seven years, began to feel an unfamiliar lightness in her chest. It reminded her of doing ecstasy.

By 7 P.M. Larry was roasting wienies on a rusted hibachi and had invited a couple of friends over: Peter, a sandy-haired seedy-looking guy, and Mark, a very short, muscular bald man who was overly solicitous toward Susan. She couldn’t figure out why.

When it got dark she realized they needed a light to shine in the skunk hole. All Larry had was a lava lamp. He placed it reverently by the hole.

Larry went on another beer run. By eleven they were all having loud, earnest conversations. Susan felt comfortable enough (read: drunk) to voice her opinions on classic rock to the bald guy, who was confounded. “Man, that’s just not right,” he said, shaking his head. Larry shocked Susan by displaying a casual knowledge of all the twee bands. It turned out he’d been a roadie/dealer to half of them. He even claimed to have gotten a blow job from Courtney Love.

Susan definitely had to work the next day, so she finally crawled to her bed at about 1 A.M. She left the boys on the porch listening to “Stairway to Heaven” and exhorting the skunk to climb it. She wiggled out of her jeans and fell on her bed in her T-shirt. Problem was, her bedroom window looked out on the street and she could still hear the music. It was loud. She closed the window, put some Kleenex in her ears, and passed out. In a pre-sleep fog Susan thought she heard yelling and swearing, but it soon mingled with a mangled dream about a dance in a cave and then blackness.

She awoke at six, choking on skunk stench, opened her window, and looked out. The blaster was still in place, tuned to the plummy voices of a morning show. The clear, bassy sounds were obscene in the June dew. Smog had yet to collect over the city. It was a sweet, pure morning, innocent—like it was every morning—of what a foul, exhausting day it would turn out to be. A crack baby of a day. Beer bottles stood guard on the porch next door. They must have poked the skunk out and it had sprayed. Great. She dressed blearily and went downstairs. The smell was worse in her living room near the porch. Her eyes stung and her stomach roiled. She decided to take a shower and head off somewhere for breakfast.

Leaving, she turned the radio off. It had obviously done its job.

The skunk actually hadn’t left. She and her babies were annoyed by the stomping on the porch and the music blasting into their den like firehoses. They were delighted when the radio was turned off. Spooked mother skunk would probably not leave the den for a while to get food. Now she had an idea that something wasn’t right.

Marta looked up before Susan had even entered her office.

“What is that smell? ’ she demanded, as Susan entered.

Susan’s mouth pursed and her head cocked in an expression of guilelessness that drove Marta mad.

“You mean you can smell it? ” asked Susan. “The cab driver didn’t say anything.”

Susan knew she was taking too many cabs and she immediately looked guilty, making Marta even more exasperated. Susan’s hair was wet and rumpled and her skin was red and blotchy from the beer. She was wearing a wool plaid skirt with a purple sleeveless blouse. It was so hard to decide what to wear in the spring. Goosebumps dotted her arms like Cream of Wheat. Marta’s magenta lips compressed.

“Please sit down, Susan,” she said in her level, barely accented speech. “Are you feeling better? ”

“Oh yeah,” replied Susan, forgetting for a second she had called in sick the day before.

“I’m afraid you have been absent a little too much lately and have been coming in late from lunch too often,” said Marta.

“Oh yeah, I sometimes get caught up in a book at lunch. Sorry,” smiled Susan.

“Well,” said Marta, “it is important that we can rely on each other here. What if the minister asked for one of your projects while you were gone? He expects you to be here and I expect you to be here….What is that smell?!”

“Ohm, well,” said Susan, “it’s a skunk.”

“A skunk? ”

“Yeah, there was one under my porch and my next door neighbour tried to chase it out last night and it sprayed.”

“You are going to have to go home immediately and change,” said Marta.

“All my clothes must smell the same,” said Susan.

Marta inhaled through her teeth. “Is the release done? ”

“Yeah,” said Susan.

“Go home,” said Marta. “I am officially warning you and putting you on probation for consistent tardiness. If in the next month you do not “clean up your act” (she said it in quotations, like she was parroting the latest teen expression) you will be fired and given a two-week severance package.”

“Two weeks’ free money!” was Susan’s first thought. Lately, thinking ahead was not her forte.

“Would you say you laid me off, so I could get unemployment? ” she asked.

“No, I cannot do that,” said Marta with satisfaction. “That would be untrue.”

Susan had a brief, sickening realization of how awful people could be. It’s a wonder there aren’t more murders, she thought, looking at Marta in her cheap lipstick, about to destroy her life. It’s a wonder.

Susan was about to take the subway home but realized she was probably too stinky. Besides, she had no money. Well, she had two dollars and eighty-three cents. So, she trudged for forty minutes along a one-mile stretch of a four-lane street lined with office towers, then over the bridge and up the major thoroughfare to her home. She was surprised how long it took and how little there was to see. Her knees, unaccustomed to movement, began to ache. No job. Sore body. Debt. Hungover. Being forced to walk. “Why, that’s poverty!” thought Susan. “So this is how it happens.” She remembered she had no booze at home. Four days from payday (possibly her last payday) and broke, she had squandered her last few bucks on yesterday’s beer and the cab to work. She turned up her path. Larry was mortaring a concrete block over the skunk hole. It looked awful. Her first thought was whether or not Larry had beer.

“Hey,” she said.

“Hey, man,” replied Larry.

“Skunk sprayed last night,” she said.

“Oh yeah,” he said, “I’m going to sleep in the backyard tonight.”

Susan pictured Larry’s backyard. Weeds, sorry-ass balding grass, rusted tins.

“Um, we don’t know if it’s gone yet,” Susan said, gesturing at the concrete block. “You might be sealing it in. We have to do the newspaper thing and see if it’s left.”

Crouched with one arm over his knee, he looked up at her.

“Fuck, man, after last night, it’s gone.” He winked. “Turned off the radio on its way out.”

“I dunno,” she said.

She stood there awkwardly for a second. Larry went back to sweeping the putty knife over the sides of the concrete block. Susan walked to her door and went in. She pictured the skunk trapped under her porch and felt an empathic moment of sheer panic. No, it’s gone. It must be gone. The skunk smell was still pretty bad in her living room. She went upstairs. It was bad there, too. She went around the house and opened all the windows. She sat on her grimy bed. She couldn’t sleep here. She would have to crash at a friend’s house. She called three friends. Either no one was at home or they were screening their calls. Well, she would have to sleep in her room or maybe drag her mattress to the kitchen floor in the back of the house.

She got up and ripped the sheets off the bed. She tried to grab the slippery wide side of the mattress. A fingernail immediately bent back.

“Fuck!” screamed Susan as she kicked the bed. Edging her shoulder under the mattress, she managed to hoist it onto its side on the floor. It wobbled for a minute before majestically falling away and crashing into her dresser.

“You O.K.? ” It was Larry’s voice, just feet away under her bedroom window.

Susan skittered over to her window, dodging the mattress and slipping on books. “Uh, yeah. Just trying to move my mattress. I can’t sleep up here.”

“You want any help? ”

Susan looked around her room. It was sprinkled with inside-out pants and dirty underwear. Her mattress had several faint constellations of old bloodstains on it.

“No, it’s really light,” she said. “That’s O.K.”

She hefted the mattress onto its tall side and leaned it toward the door of her room where it fell satisfactory onto its long side. “There,” she said.

She slid the mattress down the small hallway to the top of the stairs. She figured she might as well just let it slide down. It bumped down satisfyingly, knocking over the end table beside her front door. Keepsakes and pennies flew. No big deal, thought Susan. She hopped down the stairs. There was a knock on her door. It was Larry.

“You need any help here? ” he asked through the screen. “Oh, come on. Let me get this.”

He came in and grabbed one end of the slumped mattress, trapping Susan against the wall with it.

“Hang on,” he said, and twitched it straight. He snapped his head back, sniffing.

“Fuck, it’s bad in here.”

“Yeah, well, it’s right under my living room, really,” said Susan.

Larry expertly dragged the mattress down the hall to her kitchen. In his element. Give some men a task at hand and that’s the only time they seem to fit, thought Susan. He looked perfectly respectable, even nice, helping her out. This was his department, like sealing off the base of the house. Fred had always looked flustered when he was painting or moving furniture.

Larry got to the kitchen and Susan, looking at the oily dust bunnies clawing from under the fridge, and the sticky soda stains on the floor, changed her mind.

“You know what? ” she said. “Let’s take it out to the back porch.”

“Yeah? ”

“I think I better sleep outside too.”

“Yeah, you better,” he said.

After Larry left, Susan couldn’t sit in her living room, drink, and watch TV as per usual, so she decided to clean up instead. By the time it was dark she had done all her laundry. She had also swept up her porch, raked the backyard, and hung a line for her wet clothes. She scoured her kitchen floor, did her dishes, cleared up her bedroom, and swept. She brought her alarm clock down to the porch so she could get to work on time. She really couldn’t be late again now. Although it was an unusually muggy day for June and the insects were blooming, the nights were still cool. She made up her bed on the porch and piled every blanket and her old, torn sleeping bag on top. During all this work she had a flicker of worry about the skunk. If it was still there, how long would it take to die?

“Do you really think it’s gone? ’ Susan asked Larry forlornly over the fence. It was midnight, and he had dragged his TV outside to watch a late show. Snuggled under her blankets she had been listening to cheap comedians’ voices and smiling when Larry barked with laughter. He had just turned off the TV. He hadn’t heard her.

“I don’t think it’s gone,” she whispered.

That night, the skunk’s triggers told her to leave. Sniffing at the concrete wall she shook her head. She started to dig. Nothing. Everywhere she dug there were barriers. She circled the den, ignoring the kits who were crying for milk. She dug for hours, her claws tearing on the steel mesh Larry had lain down the perimeter of the porch. She rested, panting. Thirsty. Ears flat.

On the second night she was weak, spraying in her distress as she circled and then stopped and then circled and dug. One of her kits had stopped moving. Soon she would stop moving too.

A noise. Hammering. Sharp acrid human smell. Human sound. The skunk huddled herself into the darkest, flattest corner of her earthen cave. Her head swayed. Suddenly light.

Larry was indulgent about Susan’s need to rip away the concrete block, even though he had spent a whole afternoon closing up the hole.

“You’re one fucked-up lady,” he laughed, but not in a mean way. Hey, chicks are like that, he shrugged. They chiselled the block out of the entranceway and he let her put newspaper over the hole. If the newspaper was dislodged that meant the skunk had left, explained Susan. The next morning, it was. More newspaper was put over the hole. After three days it remained where it was. The skunk had not come back. Proof.

That morning Larry found Susan lying on the ground. She had been on her way to work when she felt the need to lie on the ground and look into the skunk hole, the same way she’d lain on her kitchen floor sometimes. The hole still stank, but it was empty, she was sure. They could seal it up again. For a second she thought about the trapped animal, and her heart thumped into the ground and her nails dug convulsively into the earth. She was late for work again, and she was grinding dirt into her clothes. She knew she would be given her notice today.

Larry lay down beside her, his face on the ground next to hers. They breathed into each other for a few seconds. He raised his hand and ran a finger down the side of her face. “There, you see? It’s O.K. She’s gone,” he said. “She’s not dead.”