Oh God! Another story of an affair. Extramarital, mid-life, May-December. The sort of terrible thing that screws up everybody’s lives and makes you think hard about your own for a time, as though your life might, given sufficient effort, allow itself to be figured out. Have you heard this one before? Don’t answer that! Just accept my apologies in advance. Along with the explanation that this is my story and therefore carries the small virtue of authenticity. As for its commonness, there’s nothing I can do except try to point out the microscopic ways in which it might be unique. Because even the most predictable human events have their own surprises if you stick your nose in there far enough, don’t they?

So let me throw out my aces right here and now and see if I can’t convince myself: I was thirty-nine at the time, the girl was eighteen, and the whole thing ended in what some might call a symbolic death. How’s that?

Now, the names: I’m Richard (not Dick, never Dick), my wife was Alice, and the girl was Penny. The last being an anachronistic sort of name that can still be found in the small Ontario towns such as the one we lived in at the time. A name that today belongs only to drugstore cashiers or field-hockey prodigies (both of which my own Penny proudly was). Suitable for cutesy jokes (“A Penny for your thoughts!”) as well as a constant reminder of the costs involved.

There. You see? We’re already real.

We met at the gym. Both Penny and Alice, twenty years apart. In both cases it was after Christmas, I was feeling uncomfortably inflated by too much chocolate and egg nog, and dug out my membership card with ideas of some serious short-term toxin shedding. Next thing you know, I’m asking a girl to run away with me.

And Alice was just a girl at the time. Not only because she was younger then, but because of her particularly girlish qualities, such as bubble-gum popping and skirt-twirling cries of “Oh, you!” As with many young women in those days, it was as though she’d modelled her personality after Gidget.

There, next to the drinking fountain in the field house at the university we both went to, flushed from her yoga class. Tall and unsure of her limbs, twiggy fingers playing shy over her lips. I don’t remember the words we shared, but Alice seemed to find me a clever bit of naughtiness, which pleased me. Being naughty with girls is the best kind of naughtiness, a truth she seemed already aware of. We talked ourselves into eloping even though our parents weren’t against the marriage. And then things started to move pretty fast, or unbelievably slow, I’m not sure. But the gist is we got married and older, and Alice pretty much abandoned the Gidget routine halfway through the honeymoon.

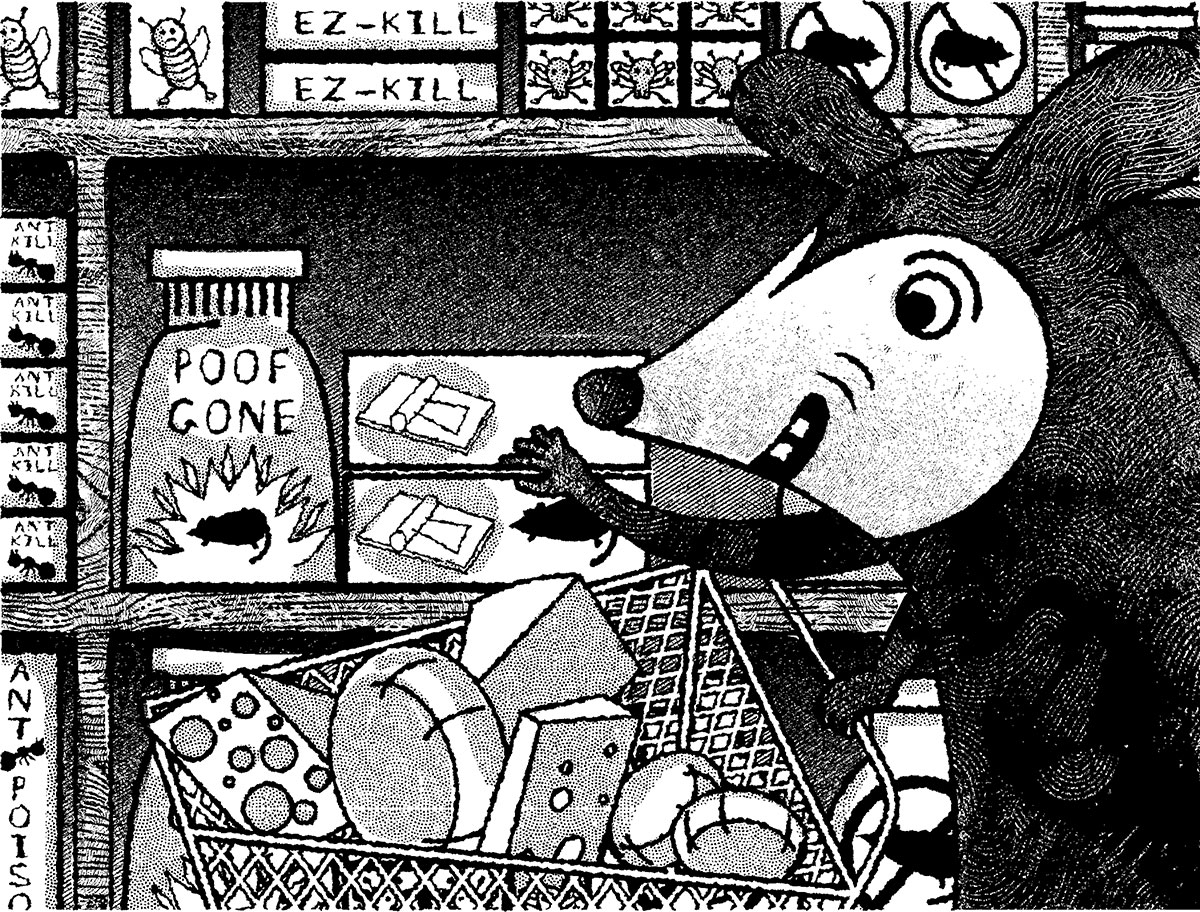

Penny was a somewhat different story. She worked at the Shoppers Drug Mart where Alice and I would pick up pads, pills, and our mostly neglected prophylactics on Saturday afternoons. A little in love with her at first sight, as I tend to be with teenaged cashiers forced to wear those unflattering, polyester apron thingies. Always a smile, a “yeah, no kidding” to any comment I might make about the weather, a whiff of lemony moisturizer rising up from the coins poured into your palm. There were three or four teenagers who worked there, and, until I really spoke to her, I confess I couldn’t distinguish Penny from the others. She was just one of the “Shoppers Drug Mart girls” who occupied my mind in the same way as the “corner store girls” and “library loans counter girls.” Pleasant faces and poking nipples to grace a small-town fellow’s day.

So this is what I did: I took a common fantasy—a settled, responsible man running off with a virgin (more or less)—and made it happen for real. Where’s the confession? I’ll sign.

Me and me and me! Where’s my Penny in all of this? There: her face moving into my field of vision as a lip-glossed moon as I lie below her on the bench press, gasping. The cashier optimism of her “Hi! Can I work in some sets with you? ”

“Of course you can,” I said, before I figured out what it was she was asking me.

Penny reset the weight to twenty pounds heavier than I was attempting (a flash of teeth to sweep away my embarrassment) and lay down to swiftly lift the bar eighteen times. She looked to me like some kind of enchanted machine, as though I’d been thrown back a few centuries and was setting my eyes upon Gutenberg’s press for the first time, printing off page after page of identically wondrous verse. A machine that smiled a lot and whose cheeks turned an almost alarming red and wore a St. Helen’s field hockey T-shirt that would have been technically considered one size too small.

Say “Penny!” out loud and the first thing that will come to my mind is how my sweetheart looked pumping away on the bench press that January afternoon. Young and almost laughably healthy, a farming-stock heart pounding inside her ribs. And, as it turns out, this first impression was pretty much correct. Her back is broad. She is a very capable girl.

“Would you like to work in? ” she asked when she was finished.

“Would you like to have lunch with me? ”

Penny looked at me without the looks I might have expected.

“What’s your name? ”

“Richard.”

“Does anyone ever call you Dick? ”

“Never.”

“O.K., Dick. But I have to be at work by four,” she says. Then I recognize her. The apron thingy. The name tag. Doing a price check on Alice’s antiperspirant.

“Penny. Right? ”

“Married. Right? ”

I bought us drive-through cheeseburgers and we ate them in the town’s only underground parking garage so we didn’t have to leave the engine running to stay warm. We had, as you would guess, precious little in common. Yet we spoke easily to each other; she about high-school characters, and me of my memories of them. A bit about her family, whom I feared. But her parents didn’t seem to care where she went, which made things go smoothly for us (although I walked past her father on the street once and held my breath as he went by, a far bigger man than I would have wished). And there was always sex to fill the time when conversation failed. Penny knew as much about these matters as I did, possibly more. I was shocked by this, over and over, which was a pleasure.

And what did she see in me, aside from a bald patch (“Does it get cold up there? ”) and an eager laugh? God knows. I’m just glad she saw something. The thought that she might have seen it before in other men occurred to me more than once, but not wanting an answer, I never asked.

At first I felt a lot of shame, but it turns out I was wrong about that. It wasn’t shame at all, really. More a particular version of happiness I’d never experienced before, an unsanctioned lightness I initially mistook for misery. This confusion had to do with my efforts at finding an explanation (for there has to be a simple, withering reason for why men like me do such things, doesn’t there?). Was it “just about sex”? A symptom of a “mid-life crisis”? An irrational response to my “fear of death”? Yes, yes, and yes. But when you’re a part of the hard situation behind such catch-alls, they tend not to mean much. How can you talk yourself out of an obsession just by recognizing it as an obsession? Yes, my life is a blissful agony since I met her, but I know that it’s only a projection or transference or glandular secretion or something, so I’ll just be heading off for some counselling now. Sorry for any inconvenience!

Not a chance. You’re already in there, it’s your life (and therefore real as anything), there’s nothing you can do. Or this, at any rate, is how I’ve come to understand my doing things I probably shouldn’t have.

Somehow, all of this had to do with the rat. It might have been a creature of a smaller scale, as I never saw it myself. Yet it was a noisy enough son of a bitch to be a rat. In those days of increasing distance between us, it was kind of nice for Alice and I to share this one domestic plague.

I should point out that we never used to fight, which made the fighting after she found out about Penny and me that much worse. I blamed her, that’s the simple fact of it. Blamed poor Alice for getting a good job at the bad university on the edge of that town, and me having to give up on my book. Oh, that’s too much just to say aloud! “My book!” More the book-that-never-was, the most talked about non-existent book of the season, the biggest runaway blockbuster in the history of Richard and Alice. Then I went and spoiled things by reading it. Printed up the few thousand words I had on the computer to take a look at how it was coming along, you know, to check out how it flowed. And it flowed right off my desk and down the toilet at the end of the hall.

I was astounded at how bad it was. Not astounded that it could be bad, mind you (for I’d always warned myself of this possibility, usually in the terrible minutes prior to the first coffee in the morning), but that it was so bad. You know what it was like? It was like picking up the phone first thing on a Sunday morning and having a stranger at the other end call you an asshole before hanging up (this has happened to me more than once since Penny and I got together). A damn nasty shock is what it is.

So I gave up on my book—my theoretical book—which, when I added it up in my head, had more or less happily consumed my mind for the preceding six years of life and marriage. Abandoned my characters (of whom I felt sure of only one, and I hadn’t even introduced her yet), my startling metaphors (all still just “in my head”), and my story (which had no ending, aside from the notion that somebody major had to die). As it turned out, giving up on all of it was easier than I would have thought. Spent a week or two looking around the town Alice had brought me to and saw that there was not a thing for me to do in it. Or nothing I wanted to do, at any rate. Nothing that looked appealing if I squinted at it through the main street windows or on the index cards of the unemployment office bulletin board.

And the whole time Alice was so supportive and encouraging—her greatest mistake. She cheered me with all my past successes and was left breathless by the wide variety of my current options. Maybe this was the break I’d needed all along! What about getting to some of that freelancing I’d mentioned, or sniffing around for part-time work at one of the county newspapers, just something small to get me started. Yeah, sure. Good idea. I’ll definitely look into it.

Oh, how I blamed her!

And then the rat arrived.

It only visited at night, and never strayed outside the kitchen, which, as luck would have it, lay on the other side of our bedroom wall. He’d like to get inside things—the back of the stove, the cupboards, the canvas sack of imported basmati rice that Alice insisted on—and make far more noise than vermin have a right to. He liked to break stuff, this rat. But, when I’d get up and turn on the kitchen light, the room would go instantly quiet. I’d fling open the cupboard doors and shine a flashlight in, each time expecting to be met with the glinting buttons of his eyes. But there was never anything but another shattered coffee mug and a trail of black turds the size of Tic Tacs.

When I’d return to bed, Alice and I would talk about the rat. We wondered if he was single or kept a family in the basement. We tried to gauge his size in precise terms, what he might feel like to lift in your bare hands. But mostly we’d talk about traps and their ethical implications. The poison: effective, but how long was the poor beast made to suffer? The “humane” trap that keeps it alive so you could release it outside: yes, but it would only come back. The glue paper: too, too horrendous, even for a rat.

So we settled on the old wood platform springer, which we convinced ourselves of having the advantage of swiftness. One second he’s licking at a hunk of Velveeta, the next his spine has been snapped. No time to swallow or blink or (the worst case scenario for us) utter a squeak of recognition. This was our hope, anyway.

I bought three: behind the stove, under the sink, the gap between the dishwasher and fridge. And every night he’d come back to play the same crazed drum solo on our appliances as before. Alice would be awake—I could feel the hesitations of her breathing next to me—waiting for the dull thwack we imagined might accompany its death. Some of the longest hours I’ve ever known, if you’d like to know the truth. On the other hand, those last nights spent listening to the clamour of the rat in our kitchen turned out to be the final intimacy of our marriage. A part of us would be touching—the sides of our calves, perhaps, or stray, entangled fingers—and the only things in our heads would be this point of warm contact and the horror that was about to happen in the next room. I was gone for good on the third morning.

And there it is: the drama of the never-caught rat. What’s it have to do with me and Penny? I think it’s about waiting. For the animal to come as it must, for the trap to snap down as it must. There’s a lure and coiled spring out there with your name on it and you will go to it as you are meant to and nothing will ever be the same again.

There! I’ve done it again. Think of the rat starting out as me, Richard, the man who set the traps. But somewhere in the middle I switch over. Somewhere in the telling I become the rat himself, sniffing out his fate in the dark.

Alice and I never had any children, a fact that probably explains my recent poor behaviour in the eyes of some. Maybe wiping goo off little chins and sleeping four hours a night prevents a man from thinking about teenaged cashiers, you never know. But I’d always said I wanted kids, which should count for something. We even tried for a while, years back, in the unspoken way of “forgetting” to take the pills and “losing” condoms in the sock drawer. Nothing happened. We tried harder. A good year and a half of conjugal privileges enjoyed the way God intended them, and not a single direct hit. I suppose we could have consulted a physician at that point, had them bring out the Petri dishes and turkey basters. But Alice never mentioned it and I felt too protective of her feelings to bring it up myself. It never occurred to me that the problem may have been mine.

Then Alice brought up China. Adoption there was quicker, so maybe we should sign up and in less than a year we could have our own little Chinese baby girl (they had a law against them over there, I was told). It was just like Alice to come up with a practical, morally-sound solution like that. How could you ever respond to it by saying, “China? Somebody else’s reject baby in goddamn China? Not a chance!” You couldn’t, could you, without being the sort of man who says such things? So I told Alice I thought it was a fantastic idea and phoned up the consulate myself to get all the forms.

And this brings us to my cancer scare. A week before we were to fly to Beijing to pick up little Xiu (they sent an adorable photo of her and everything) I get this strong idea that I have a tumour in my lungs. A pain, or something like a pain, in my chest. And breathing is difficult. But the doctor takes one look and sends me home with nothing more than a Valium prescription. Nevertheless, I’m still convinced that I have only a few days left. Alice, we can’t go to Beijing right now. Not with me and this cancer thing. I can hardly breathe!

And Alice said, “If you don’t want the baby, just tell me.”

“I do! You know I want the baby! It’s only that, right now, with the lungs and everything…Can we just withdraw our application so we can get ourselves totally set for the next go round? ”

“Richard, has it ever crossed your mind that you can actually talk to me? ”

We cancelled the flight, put our names down for the next year. Soon after that I started working on my book (the cancer in remission, as far as I could tell). And as the year went on Alice mentioned the Chinese baby less and looking for a new job in some other town more.

The baby deadline passed again, along with another set of birthdays. We started remembering the pills and finding the condoms. For a while I had these dreams where I’d lost a child to a fire or peanut allergy or something terrible. But then I’d wake up and remember that I never actually had anyone to lose in the first place. When Alice asked me what my nightmare had been about, I’d say, “Just monsters, honey,” and laugh a husband’s laugh.

I’ve thought about leaving the next part out entirely. But it happened. Was meant to happen from the very beginning, I suppose, although I couldn’t have seen it coming. Only when I woke up one morning six months ago with a pinpricky numbness down my left arm did I become aware of it at all. I didn’t tell Alice I’d made an appointment with a doctor for that afternoon. This was before she knew about things, and it was an afternoon I usually spent with Penny. As a consequence, the entire day had developed a kind of liar’s cloud over it.

But the diagnosis that came in a week later was true enough. A specialist read it out to me from a lab report that had just come back from Toronto, which made things slightly easier for both of us. It was those bastards a hundred miles down the highway that wanted to tell me I had multiple sclerosis, and not this serious but kindly fellow sitting across the desk from me.

I was on my own. I’d left Penny in the car outside because I feared the worst. Alice still didn’t know about the test or the numbness, because it was important for me to understand the problem on my own before I could tell her. Or to protect her from needless worry. Or some other reason that casts me in a less favourable light, such as I assumed Alice wouldn’t stay with me for long if she knew. Which is a funny concern to have, Christ knows, given that I was spending a lot of time searching for parking spots to do the horizontal mambo with a teenager round about then. But there it is. Better, I thought, if the news was bad, to fall in with someone new, someone who was aware that I was a lousy prospect right from the get-go. Penny was more than young enough to have a whole other life after I’d lost the use of mine. Maybe thoughts like these were crossing my mind as I sat in that specialist’s office. But they would have only been thoughts and nothing compared to the compulsions of the moment, the desire for one fresh round of love, a bye-bye wave to good sense. The need to make the kind of mess one leaves behind while living and being aware of it at the same time.

In any event, I’ve just been told that in five to ten years I’ll be making my permanent home in wheelchairs and beds with little cranes attached to them. I ask a couple of questions and get the answers, according to the current state of science on the matter. Then the specialist and I spend a silent, curiously masculine minute staring down at the page of lab results. You’d be surprised at how little you have to say after hearing a thing like that.

Now I’ve done it. And I really didn’t want to bring the Disease into this thing between Penny and me because there’s always the risk of sympathy—or worse, forgiveness—whenever bad luck is introduced. And let’s face it: it may be that I don’t deserve either.

The funny part is that I was more ashamed at the time of contracting a degenerative muscle disorder than my carrying on like some slippery pervert. I took to thinking that all the questions I had a hand in determining myself just illustrated how badly I’d wasted my time, a dishonour to my forty years of functional body parts. Besides, a numbness in the arm and a stiffening in both legs that would turn a single step into a stricken reaching out for strangers’ shoulders wasn’t why I ended up taking off with Penny. It is, as far as I can tell, a coincidence, and nothing more.

When I make it back to the car, Penny leans forward to take in my face. Asks why I’m crying.

“It’s the sun,” I say. “It’s just too bright today.”

And I believe that it was.

Love stories are allowed to cheat. Why do they get to fade out into the “happily ever after” while stories of an affair—the ugly cousins of romance—must finish with a bloody car wreck of a breakup? The rules on this are strict. If there’s no come-uppance for the adulterer, his story is no good to anyone, like a murder mystery where the killer gets away with it. So why do we continue to tell ourselves these tales when we know in advance how they’re going to turn out? I’ll give you my theory: It’s because we don’t know. Not as it’s actually happening we don’t. This may be the world’s first story of an affair where everyone understands, only minimal feelings are hurt, and bystanders refrain from judgment. There’s always a chance of a surprise twist at the end.

Penny and I live in a different town now, even smaller than the one we came from, in an apartment above a trophy store. (There’s an irony in this, I think, but maybe not. Maybe it’s just an apartment above a trophy store.) We get along well. Or better than you’d guess. Better than the national getting-along average, I would say. We still use the word “love” outside the context of an apology. My body is turning to stone, but I’m still able to hold her.

What’s left is the outstanding matter of that death I promised. I learned about it through a note delivered by my lawyer after a meeting with Alice’s lawyer (they were both busy giving Alice all the things I was happy enough to lose). It came in one of those tiny white envelopes, the kind to be found stuck in the thorny stems of store-bought roses. I knew it was from Alice before opening it, of course, and I knew it couldn’t be good. But I was curious all the same. Was it going to contain one last, hateful remark, something piercing and emasculating? I doubted it. Alice didn’t like hurting people’s feelings. Even mine, even now. But surely the message couldn’t be so big-hearted as to wish me and Penny luck, an offer of no hard feelings? Nobody had better rights to hard feelings than Alice. So how could she sum up all of our time together—our lives—in the space of a flower store card?

I waited until Penny had left for her new job at the Kwikkie Mart before opening the envelope. And when I did, it was as I sat with my back against the tub in the bathroom. For some reason I needed to be on the floor, in a small room with a closed door that locked. The taps turned on all the way to cover the sound in my throat.

Alice’s handwriting. Tall. The letters tilted over to the side as though sailing masts caught in a stiff wind.

“We finally trapped the mouse,” it read.