I’m reading the new Zoey Malone: Paranormal Detective mystery under the covers with my U.F.O. night light when I hear Conrad’s bedsprings creak down the hall. I listen for Dad and Rachel’s bedroom door to open and close. The sleepwalking started when we moved here a few weeks ago, right after we found the dam.

Dad said moving to New Brunswick was a “no brainer.” It’s “getting out from under,” it’s “living mortgage free,” and it means Conrad gets a “natural childhood.” He’s too young to remember the tiny square of grass in front of our house in Toronto, where a grillion pictures of him got taken on a blanket a little smaller than the lawn.

But I know the real reason we moved here is that Dad lost his sales job at the solar panel company.

Conrad is my baby brother, but not my real brother, because Rachel, his mom, is my stepmom. I’m not allowed to call her that, because she doesn’t like the sound of it. She prefers “sister.” She painted a peace symbol on my face at an Earth Day parade about a year after my mom died. She and Dad talked for a few minutes before she painted her phone number on his hand. She’s fifteen years younger than Dad, but he says souls have no age. When Rachel delivered Conrad, she did it holistically, in a plastic tub at home. I could hear her from down the hall, where I sat with her friends, who lit sticks of dried leaves and gave me one to wave around, cleansing the air.

“He’s going to be so special,” one of her friends said to me, raising her voice above Rachel’s screaming.

It’s so cheap to live in the Maritimes that Dad doesn’t even need to work. He says if he never has to put a suit on again, it’ll be too soon. Rachel got a job as a wellbeing counsellor with a bank here, teaching the staff how to live better through salads and yoga. Dad will stay home with us. “Rachel’s career is important,” he said, ruffling my hair that first morning, as we watched her drive off down the road, “and it’ll give me a chance to spend some time with my girl.”

We found the dam on our first walk across the property. Our new house sits on five acres of land. Dad says he’s going to plant a permaculture garden and told Rachel he’ll go out every day and pick her the perfect clove of garlic for the fancy meals he’ll make. He was holding Conrad’s hand as we walked that day, so I was the first to see the mountain of sticks looming up over the hill. My mind raced through all the animals I knew, trying to figure out what could have built it. It wasn’t birds or moose, and bears hide in caves. It must have been a witch.

“Ba-dah?” asked Conrad when they caught up, jabbing out his fingers.

Dad hoisted Conrad in his arms.

“Is that a . . . ?” I asked.

“Yeah,” said Dad after a second. He didn’t look happy. “Looks like a beaver dam.”

“Beadum,” said Conrad.

I’d done a presentation at school last year on the beaver, and I knew they built dams and lodges out of sticks, but some of these sticks were logs. The beaver is our national animal and is also a symbol of Canadian industry. Their teeth contain iron. For my presentation, I included a picture of a giant maple trunk chewed right through by a beaver, to demonstrate the power of their jaws and commitment to labour. They never get tired of chewing. The beaver is the only other animal, next to humans, that can do as much to change their environment. I thought I knew everything about beavers, but I didn’t know they could build anything this big.

“O.K., let’s go,” said Dad, putting his hand between my shoulder blades and steering me back toward the house.

That night, for dinner, he made a whole wheat pasta with field mushrooms, lemon zest, and Parmesan.

“Rachel, I found a beaver dam!” I said when we sat down at the table. “Right down at the creek! It’s huge!”

“Beadum!” Conrad spluttered from his high chair.

“Wow,” she said, giving him big eyes and wiping his drooly chin. Then she looked at Dad.

“Beavers,” she said, raising her eyebrows.

“Mmm,” said Dad, raising his eyebrows back and tucking a noodle in his mouth with his fork.

“Why didn’t the realtor say anything?” she said. “That’s an infestation.”

“I don’t—”

“You know a man in Belarus got killed by a beaver last year,” Rachel said. “Walked right up and bit his leg, David. It severed a femoral artery. He bled right out.”

“Rachel—,” said Dad.

“It has to go,” she said to her pasta.

“You can’t just destroy those things,” said Dad. “They’re a part of the ecosystem. We could end up killing whole species of fish if we get rid of—”

“Well, what do you suggest, David?” she said, “Are you going to pick them some garlic?”

“It’s illegal, you know,” he said. “There are fines.”

“Well, I’m sure you’ll come up with something.”

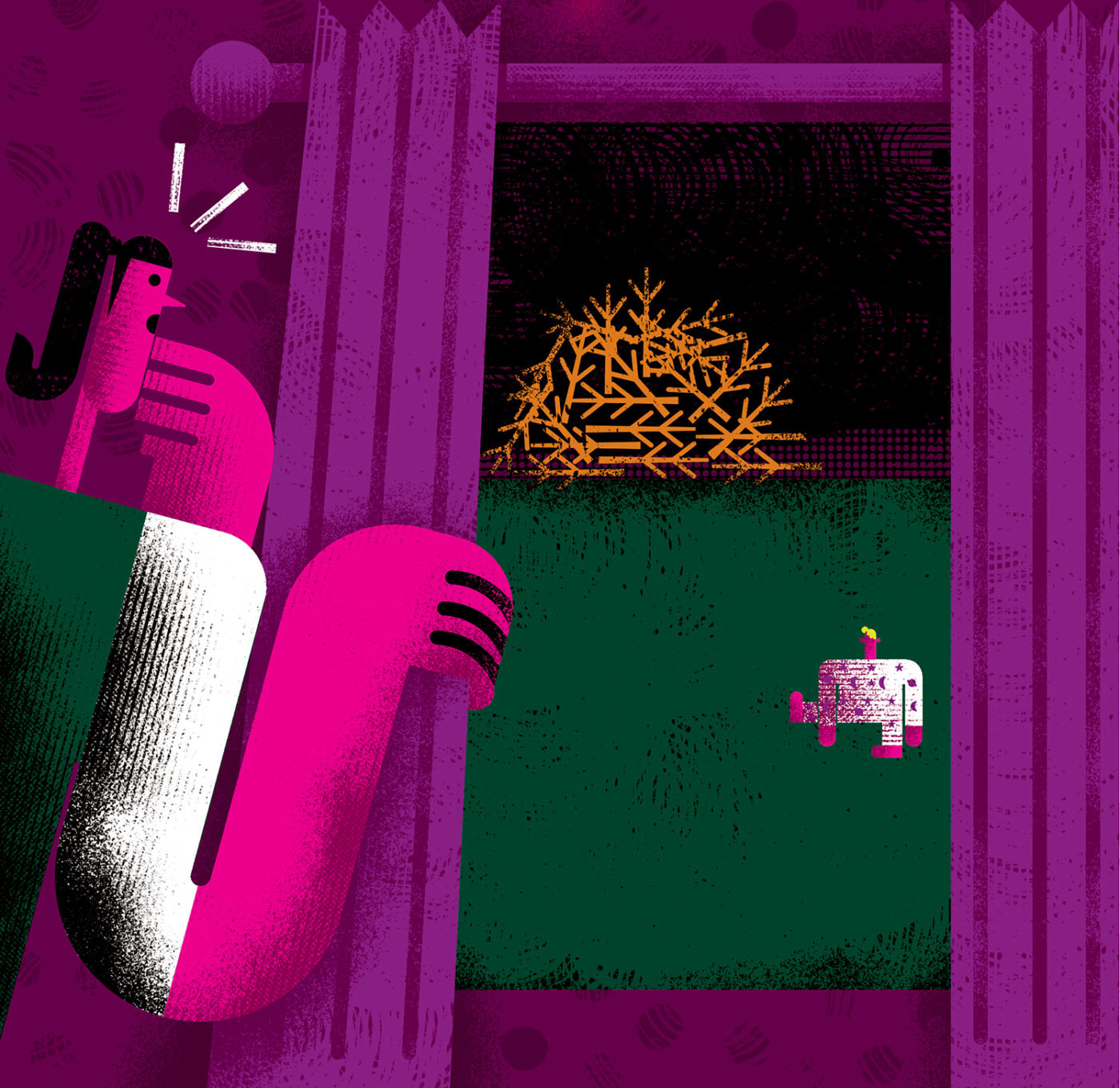

That night, I heard the front door latch after I was supposed to be asleep—sometimes, Rachel smokes cigarettes. But it wasn’t Rachel. It was Conrad. I looked out my bedroom window to see him in his spaceship pyjamas, walking barefoot across the property, toward the dam, like a zombie. I ran downstairs and caught him before he reached it. He was dead asleep.

Dad and Rachel had another fight at breakfast.

“It’s stress making him act out,” said Rachel. Dad exploded into a tiny laugh.

Conrad does it every night now. He gets up, pees on the floor, and heads for the dam. Dad installed a gate at the top of the stairs and extra high chain locks on the front door. He and Rachel had another fight at dinner where he said, “We don’t always have to go storming in like the paratroopers, Rachel.”

If you catch Conrad in time, you can guide him to the bathroom and he does the whole thing in his sleep. You can tuck him right back in without even waking him.

The toilet flushes and two sets of footsteps rustle down the carpet toward Conrad’s room. The springs groan and his bedroom door closes. I listen for the sound of Dad and Rachel’s door, but instead, the gate at the top of the stairs opens and clicks shut, feet pad down the stairs, the high chain on the front door tinkles against the frame. I run to the window to see Dad heading barefoot across the yard, toward the dam. It’s hard to make out colours by just the sliver of moon outside, but I know because I watched him go off to work every morning for all those years, that he’s wearing his blue suit.